By Candela Palacios (CS Staff)

“Dad, tell me again, why did you have to go so far away?”

“We hoped that way the claim for our land would finally be heard, my son.”

“But is the land not already ours?”

“Yes, son. It always has been. But some people want this fact to be forgotten, as we ourselves have been.” *

More than 2,000 kilometers, or 1,200 miles. This was the distance covered by more than 100 Indigenous representatives from different communities, sometimes on wagons or donkeys, sometimes on foot, during the almost three-month march called "El malón de la paz," or the “Peace Raid,” in Argentina in 1946. The term malón, which, in the Mapudungún language spoken by Mapuche Peoples, means a surprise collective invasion, was adopted by several South American countries to describe a type of military action carried out by various Indigenous Peoples to fight against the theft of their ancestral lands.

The term was appropriated and reclaimed by Indigenous representatives in 1946 to describe their peaceful march from Jujuy, Argentina, to the country's capital, Buenos Aires, to demand the return of their lands from the newly elected president, Juan Domingo Perón. During his election campaign, Perón had promised to expropriate large estates in order to return the land “to those who work with it.” In the end, however, the promise was not kept, and the Malón's demands went unheard. After being paraded through the city for a few days, the maloneros were forced onto a train and sent back to their territories, where landowners and foremen awaited to punish and enslave them back into work on the vast sugar plantations.

History repeated itself in 2006 when a second, or Segundo Malón de la Paz, marched from the capital of Jujuy to Purmamarca to demand that the provincial government return their land, a right now guaranteed by the 1994 national constitutional reform. Article 75 of the new constitution, clause 17, recognizes the pre-existence of Indigenous Peoples in the Argentine nation. This pre-existence gives Indigenous Peoples the right to own their ancestral lands and to participate in the management of their natural resources. But in order for the land to be returned, it had to be properly demarcated. Emergency Law 26.160 was therefore passed at the end of 2006 with the aim of completing the demarcation process in a maximum of three years. Due to a lack of political will and a conflict of interests, the law has been renewed three times, and the demarcation of the land remains unfinished.

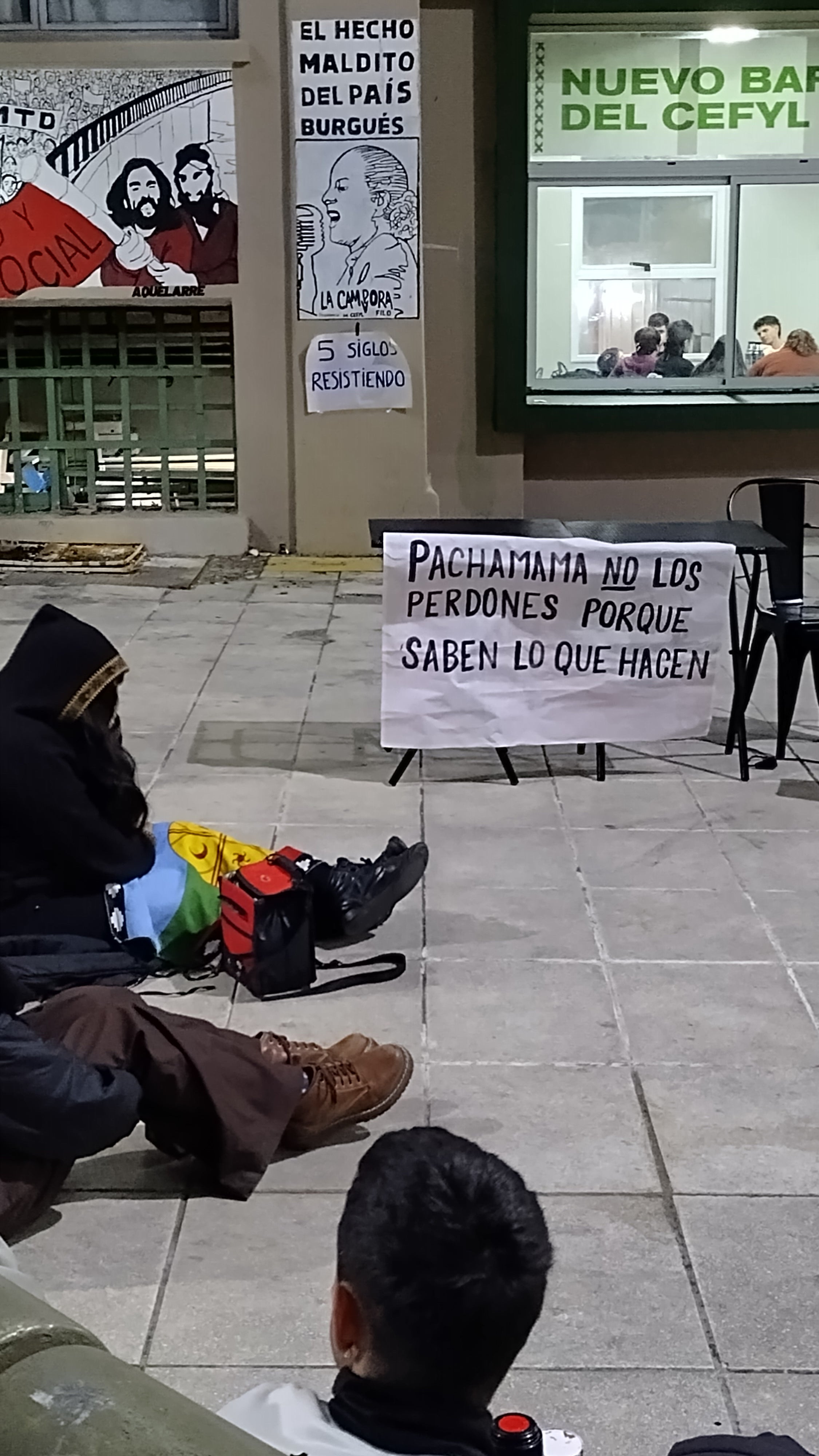

Sign saying "Pachamama, do not forgive them, for they know what they are doing."

In the early morning of June 20, 2023, after a hasty process and behind closed doors, the government of Jujuy approved a reform of the provincial constitution. The discussion and drafting of the new text took place in the midst of protests started by teachers demanding better working conditions and later joined by other social groups. The amended articles of the constitution allowed international mining companies easier access to lithium reserves, which are located on traditional Indigenous lands and also banned the right to protest, among other anti-democratic actions.

The constitutional reform was carried out in violation of the right of Indigenous Peoples to Free, Prior and Informed Consent to projects affecting their land and well being, as enshrined in ILO Convention 169 and sanctioned by the Argentine Congress in 1992. It was met with fierce resistance from various sectors of the population, including Indigenous communities, who protested in the provincial capital and in various towns and villages, mainly by blocking roads. These protests were violently repressed by the armed forces, resulting in mass arrests, ill-treatment, and the injury of many demonstrators; one minor even lost an eye to a rubber bullet.

As the weeks went by, national media coverage of the situation diminished. In the midst of the conflict, Jujuy's governor and main proponent of the reform, Gerardo Morales, was selected as the vice presidential candidate for the right-wing party, Juntos por el Cambio (Together for Change, or JxC), which governed Argentina from 2015 to 2019. The conflict in Jujuy may have affected the party's results in the August 13, 2023 primaries, in which both JxC's proposed lists and the candidate of the current Peronist government were outperformed by the far-right libertarian candidate, Javier Milei.

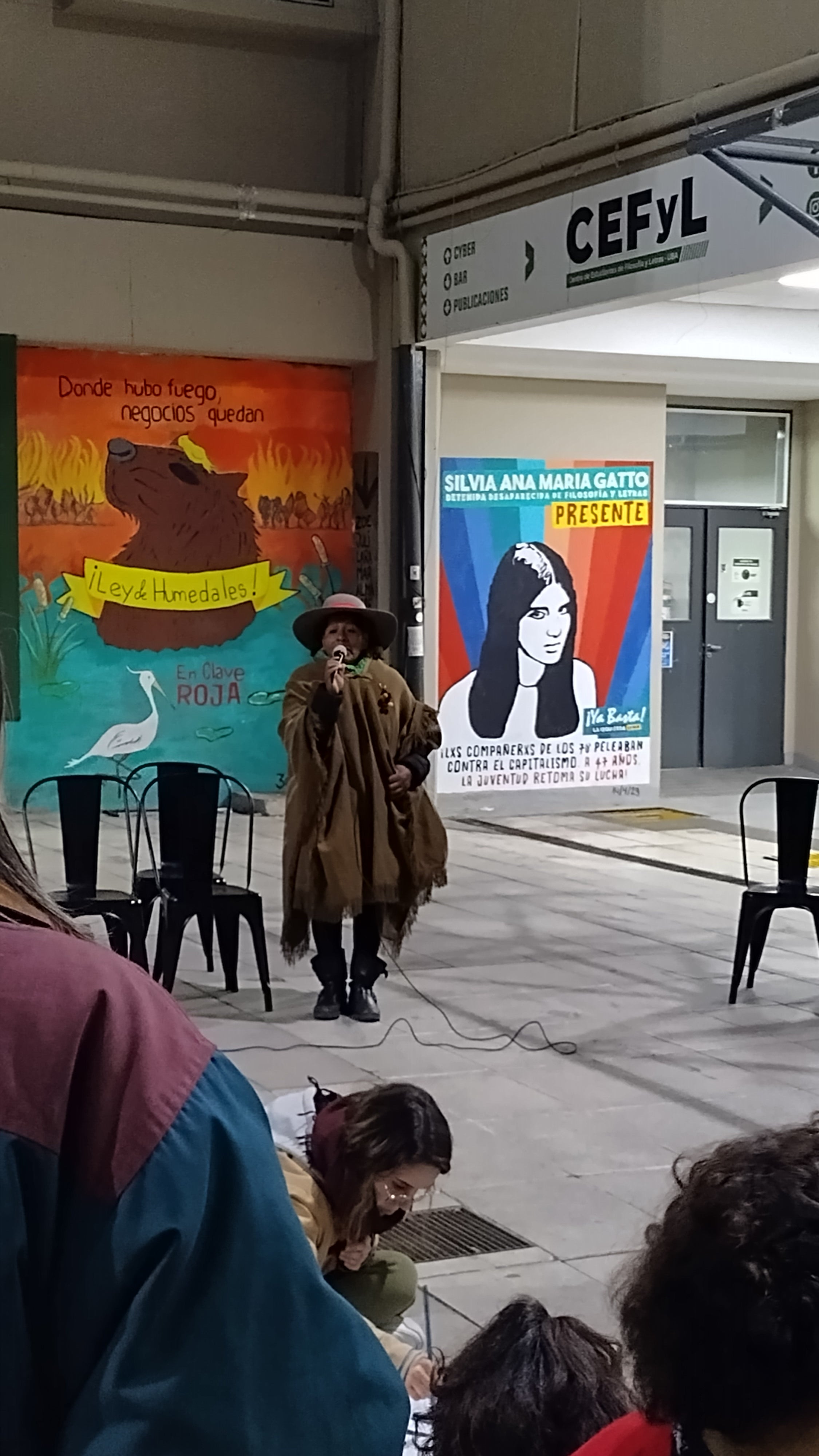

A malonera shares her experience about how the constitutional reform affects her and her family, and why it is important for everyone to support their cause.

As the protests and repression continued, several Indigenous representatives from Jujuy came to the conclusion that their demands would not be heard in their province. For this reason, on July 25, they set off for Buenos Aires in what they call the third, or Tercer Malón de la Paz. The caravan, this time with the help of motorized vehicles, passed through several cities and was received with solidarity. The march is composed of over 200 people, and some of the older maloneros are the children of those who made the original journey in 1946. The Tercer Malón de la Paz arrived in Buenos Aires on August 1, an important day for the Indigenous Peoples of the region, as it is the Andean and Amazonian New Year. On this day, many Indigenous communities celebrate by arising early to await the arrival of Inti (the sun), which marks the beginning of a new cycle, and to make offerings to Pachamama, or Mother Earth, in return for her gifts and to ask for health and prosperity.

The third Malón was not received with the same respect in the capital. As the demand this time is for national law to intervene and stop the illegal amendment of the provincial constitution, the maloneros tried to set up camp in Plaza Lavalle, a park facing Argentina's federal courthouse, Palacio de Tribunales. But Buenos Aires’ government (whose head, Horacio Rodriguez Larreta, is the JxC candidate for president) did not allow them to set up tents on the Plaza, forcing them to endure the cold winter nights and rainy days without shelter. The Supreme Court has refused to receive them, claiming that the judges’ schedules are full. Three maloneros chained themselves to a fence and went on hunger strike, but the Tribunal was unmoved.

In late August, after weeks of peaceful demonstrations, and with the support of activists and Argentina's Nobel Peace Prize recipient, Adolfo Perez Esquivel, some left-wing and Peronist legislators, including the country's Secretary for Human Rights, finally received a number of representatives. The President of Argentina, Alberto Fernandez, also received some representatives and signed an agreement in which he promised to create a Commission of Inquiry on Institutional Violence within a week. To date, this Commission has not been created.

Political figures are not the only ones to show indifference to the Malón's cause. In early September, a TV reporter met two maloneros traveling on the subway, and when they greeted her in Quechua, their language, she began to mock them, supported by the newscasters in the studio. Although many people criticized this behavior as racist and disrespectful, the show's presenter only apologized “for making anyone feel uncomfortable,” and did not address the blatant discrimination and racism prevalent in Argentine society.

Despite the mistreatment, discrimination, and indifference they have faced for more than a month in Buenos Aires, the Malon remains strong. Many people are supporting their action, helping them with supplies and providing them with places to use toilets and showers. On August 25, a group of maloneros came to the Faculty of Philosophy and Arts of the University of Buenos Aires, where I had the opportunity to listen to them. Many said they were afraid to return to their homes and families because they did not know how far Morales' police would go, and they were afraid of becoming Desaparecidos, the term used to describe the more than 30,000 people kidnapped, tortured, murdered, and disappeared by Argentina's last dictatorship, which ruled the country from 1976-1983.

Still, the Malón resists. Both in Buenos Aires and at the roadblocks in Jujuy, the maloneros are fighting and asking people to listen, to join them in their demand for justice. They say this is the only way to force governments to prioritize the present and future well being of the people over the interests of international mining companies, who claim that transitional minerals are the key to a sustainable future, but fail to consider the lives of those left with a devastated land, those whose skin is darker and who speak a different language, “the Other;” the people who have lived on the land for thousands of years, respecting it and defending it from harm, and who assure us that they will continue to do so if it is the last thing they do.

*Dialogue reconstructed from the account of a malonero on his visit to the Faculty of Philosophy and Arts, University of Buenos Aires, August 25, 2023.

Top photo: Maloneros on their visit to the Faculty of Philosophy and Arts, University of Buenos Aires, Argentina, August 25th.

All photos by Candela Palacios.