By Marianna Sanborn

In mid-September, an account of the deplorable conditions of immigrant detainee camps in Georgia was made public, bringing to light the alleged continued use of sterilization on immigrant women.

Project South, a nonprofit based in Atlanta focused on the elimination of poverty and genocide, issued formal complaint against the Department of Homeland Security and ICE. Ms. Dawn Wooten, a nurse at Irwin County Detention Center (ICDC), revealed in the complaint that several detainees were undergoing sterilization procedures without their full understanding or consent. In the report, it states, “One detained immigrant reported to Project South that staff at ICDC and the doctor’s office did not properly explain to her what procedure she was going to have done. She reported feeling scared and frustrated, saying it “felt like they were trying to mess with my body.” When she asked what was being done to her body, she was given three different responses by three different individuals.” High rates of hysterectomies was also mentioned in the report, as well as a lack of COVID-19 testing and health safety precautions.

According to an article from Reuters, the Mexican Foreign Minister stated that none of the detained women of Mexican descent at the Irwin County Detention Center have been subjected to such procedures, also stating that a federal watchdog will be brought in to investigate such complaints. However, “an investigation was ongoing as more women still needed to be interviewed. Earlier this week, Mexican officials said they were interviewing at least six women who may have been subject to improper medical procedures, including hysterectomies”.

Several top Democrats have spoken out about the report, including Speaker Nancy Pelosi: "If true, the appalling conditions described in the whistleblower complaint – including allegations of mass hysterectomies being performed on vulnerable immigrant women – are a staggering abuse of human rights...". On September 15, 2020, at least 170 members of Congress wrote a statement to the DHS Inspector General Joseph Cuffari calling for an immediate investigation into the complaint.

The Project South report, while shocking, is not to be seen as an exceptional or new occurrence of racism within the medical field or the American immigration process. A history of forced sterilization of Indigenous and minority women can be linked to the eugenics movement, popularized in the early 20th century. The U.S. has a long history of reproductive injustice for Native American women. Government services such as the Indian Health Service (IHS) used sterilization procedures as a way to limit population growth of ‘genetically inferior’ racial groups. The Family Planning Services and Population Research Act of 1970 allowed physicians to subsidize procedures via the IHS, sterilizing approximately 25 percent of Native American women, or around 3,406 women according to the U.S. Government’s admittance to the procedures 6 years later. Sterilization racism- disproportionate number of sterilization procedures on Native American and Indigenous women- is a form of genocide. Removing the ability to bear children without the total consent or awareness from the mother is a human rights violation.

More broadly, medical racism and the act of performing experiments and procedures on people of color is also a continued event in American history. For example, the U.S. government’s experimentation on Guatemalan citizens left at least hundreds of ‘test subjects’ without access to treatment or justice for the harm they faced. Rodriguez and Garcia write: “Beginning in 1946, the United States government immorally and unethically—and, arguably, illegally—engaged in research experiments in which more than 5000 uninformed and unconsenting Guatemalan people were intentionally infected with bacteria that cause sexually transmitted diseases. Many have been left untreated to the present day.”

Additionally, U.S. Government control of Puerto Rico throughout the early 20th century and up until the mid 1960s led to approximately one third of all Puerto Rican mothers, ages 20 to 49, being sterilized. Rather providing Puerto Rican women access to alternative forms of contraception that are safe, legal and reversible, U.S. policy promoted permanent sterilization, oftentimes without stating that the procedure was permanent. The continued use of eugenics theory allowed the U.S. government to force such procedures, “citing concerns that overpopulation of the island would lead to disastrous social and economic conditions.”

Language exclusion, particularly for Indigenous Peoples, creates dangerous and confusing pathways through healthcare and through immigration. The migration experience into the U.S. by Indigenous people is “characterized by unique vulnerabilities, which stem from our Indigenous identity and the intersection of discrimination, racism, and language, ” explain Juanita Cabrera Lopez (Maya Mam), Patrisia Gonzales (Kickapoo, Comanche and Macehual), and Blake Gentry (Cherokee) in a joint article published in the Cultural Survival Quarterly. Language exclusion, misclassification of Indigenous identity, and lack of transparency in immigrant detention centers have left Indigenous women at extreme risk in the hands of ICE and the Department of Homeland Security. “Indigenous migrants do not receive equitable treatment because they are not recognized as part of Indigenous Nations with a right to communicate in their primary languages,” they continue.

There has yet to be a formal investigation report produced by the DHS. The whistleblower report offers a new opportunity to reassess and formally investigate the alleged continued practice of nonconsensual sterilization of Indigenous and immigrant women, which is vital to the human rights to health of Indigenous Peoples under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

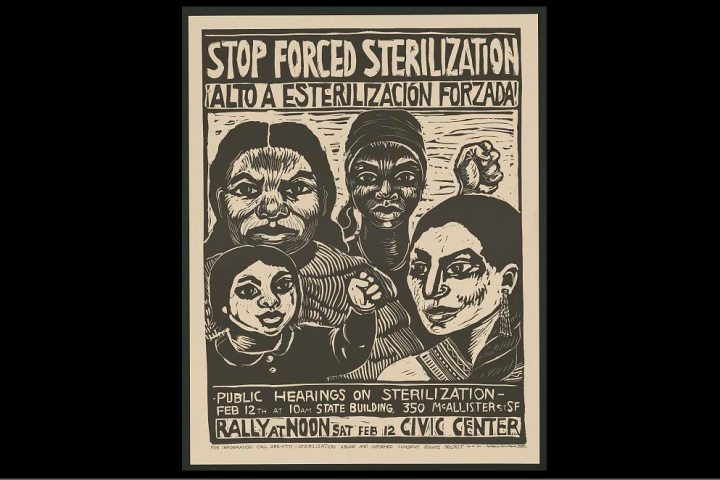

Image: Poster for a 1971 rally against forced sterilization in San Francisco, CA designed by Rachael Romero. (Library of Congress)