Many Indigenous languages do not have a large canon of written literature, and because of that, they are often and wrongly referred to as oral languages. Every Indigenous culture has its own form of literature and means of conveying knowledge through its language; most Indigenous languages have had a written form, often with a non-alphabetical system that was eradicated by colonization. In recent decades, many Indigenous Peoples have resumed their written tradition, either through recovering their ancient writing systems or by adapting to the alphabet of the colonial language dominant in their region.

For modern Indigenous people, having a body of literature in our Indigenous language has become a central focus in the process of strengthening our languages and defending our right to transmit them to future generations. One of the newer efforts to support the growth of written works in Indigenous languages is StoryWeaver, an open source platform from nonprofit publisher Pratham Books. Aiming at underrepresented languages, StoryWeaver offers a free online platform where users from any part of the world can read, create, and translate stories to the compendium of written literature in their languages.

Purvi Shah and Amna Singh are Senior Director and Senior Manager, respectively, of the StoryWeaver platform. Shah says that StoryWeaver was born out of a desire to get a book into every child’s hands. “Most of the children’s books that were available at that time were very expensive and beyond the means of children who studied in public libraries. That was the reason we set up Pratham Books, so that we could make the storybooks affordable,” Shah explains.

Pratham Books was established in 2004 in India, a country where more than 370 languages are spoken, so the challenge of reaching such a goal was significant. After publishing high quality, affordable books in different languages, an important conversation started among the staff: What would it truly take to get a book in every child’s hand in every language? Eventually, the publishers learned about Creative Commons licenses. “We were doing little things here and there to see what would happen if we freed the books from the chains of copyright. What could that really do for our readers? What could that mean for

access? What would that mean for the child? And what would that mean for the community that was working with the child?” Shah recalls.

The public response was promising. "There were people who found a handful of our storybooks published on an open source platform called Scribd, and took it upon themselves to translate, and re-upload them on the platform. This showed us that there was a community that would be willing to stand by us if we wanted to make this dream of a book in every child's hand come true," Shah says. Now, in the open source platform, an editorial team works with freelance authors, illustrators, and translators to make these high quality books come together. The content “is inherently diverse because we work with illustrators and authors across the country. So their design styles and their own ethnic identities are reflected in those storybooks. That content would come to us in one or five languages, and then it gets amplified on the platform,” Singh says.

There are several ways of participating in StoryWeaver. A user can read a book online or save it to read offline later without losing the experience flipping the page. A teacher can download a PDF version to print and share in the classroom. People can translate a story to get a new book reusing the original design and images, either online or offline. Authors are welcome to create original stories and upload original images for free usage under the Creative Common licenses so others can read, translate, or reuse them. The Creative Common licenses open a wide range of possibilities for parents, authors, educators, translators, students, illustrators, and literacy programs.

People working with Indigenous languages have found StoryWeaver to be an invaluable source of solutions and ideas and have created new ways of taking advantage of the platform. Shah talks excitedly about a visit to the Triqui Peoples in Oaxaca, Mexico, with whom StoryWeaver partnered via the Endless Oaxaca Multilingüe project of the Fundación Alfredo Harp Helú. The Triqui “went beyond,” Shah says. “They actually took all assets from the platform—an image, text, a storybook—and then they created a whole literacy program around that one storybook. Until we visited and saw it in the classroom, we had no idea that this is how all the assets from the platform were being used so creatively by the teachers. There is no one, two, or three ways of using StoryWeaver. It is what you make of it.”

Other publishers outside of India, notably BookDash, the African Storybook Project, and Sub-Saharan Publishers, have added some of their best-selling books to StoryWeaver, which have now been translated into Indigenous Indian languages. India’s Gondi-speaking community has also managed to get books in their language through StoryWeaver. “They hadn’t ever seen their own identity reflected in a storybook. It was a moment of pride,” Singh says. Speakers of the Toto language, a critically endangered language in India, used the platform as a repository to archive their wisdom and language, which is down to its last 200 speakers.

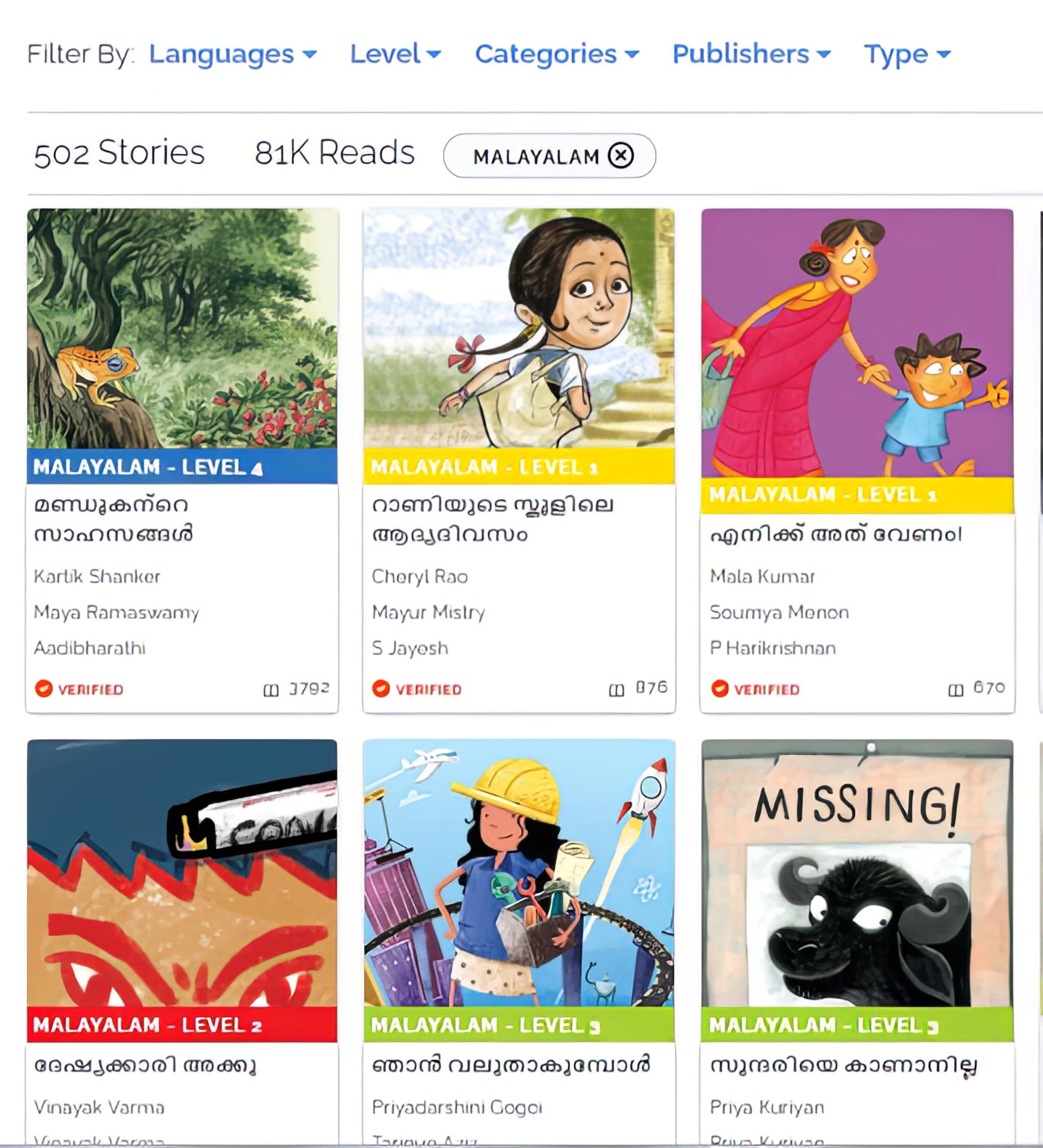

Examples of books published in several languages.

StoryWeaver’s close attention to the user experience has helped the platform to grow and reach more people. With teachers in mind, the team designed a virtual bookshelf to collect storybooks and have them readily available for the classroom. They also enabled translation on mobile devices. “Many of our [translating] partners didn’t have access to laptops, so we created that [for them],” Shah says. StoryWeaver also has phrase-level dictionaries available for a few Indigenous languages and even input tools that convert Latin characters into other scripts. “Digitizing a language or having an input tool is probably a very first step to make the language sustainable in the digital world,” Singh says. Currently, 225 of the 350 languages on the StoryWeaver platform—64 percent—are Indigenous.

Given the open nature of the platform, the team has made available a tool to red flag a story if users find anything inappropriate in the story or the images. Readers can also rate stories to showcase the best content. “We want to make sure that they come in, that they have a good experience reading and translating the story, and then they can take it to the child,” says Singh. “We do have representation in 300-plus languages, but we need more collaborations around high quality translation, more of those local tales from across geographies and across communities, and a better representation of that on the platform. We need philanthropic funding. That’s always the need. More partnerships are required so that high quality translation for children’s literature happens,” Shah says.