My people, the Karuk people, live along the midstretch of the Klamath River in northern California, where there are three annual Pikyaavish, the Karuk American word for “World Renewal Ceremony.” In the old days, this ceremony was the paramount step in individual and collective spiritual consciousness. The ceremonies occurred at the upstream and downstream ends of our world and at our world’s center. The World Renewal is a communal ritual that reenacts the creation, recreates and renews the earth and the Spirit Beings of the earth.

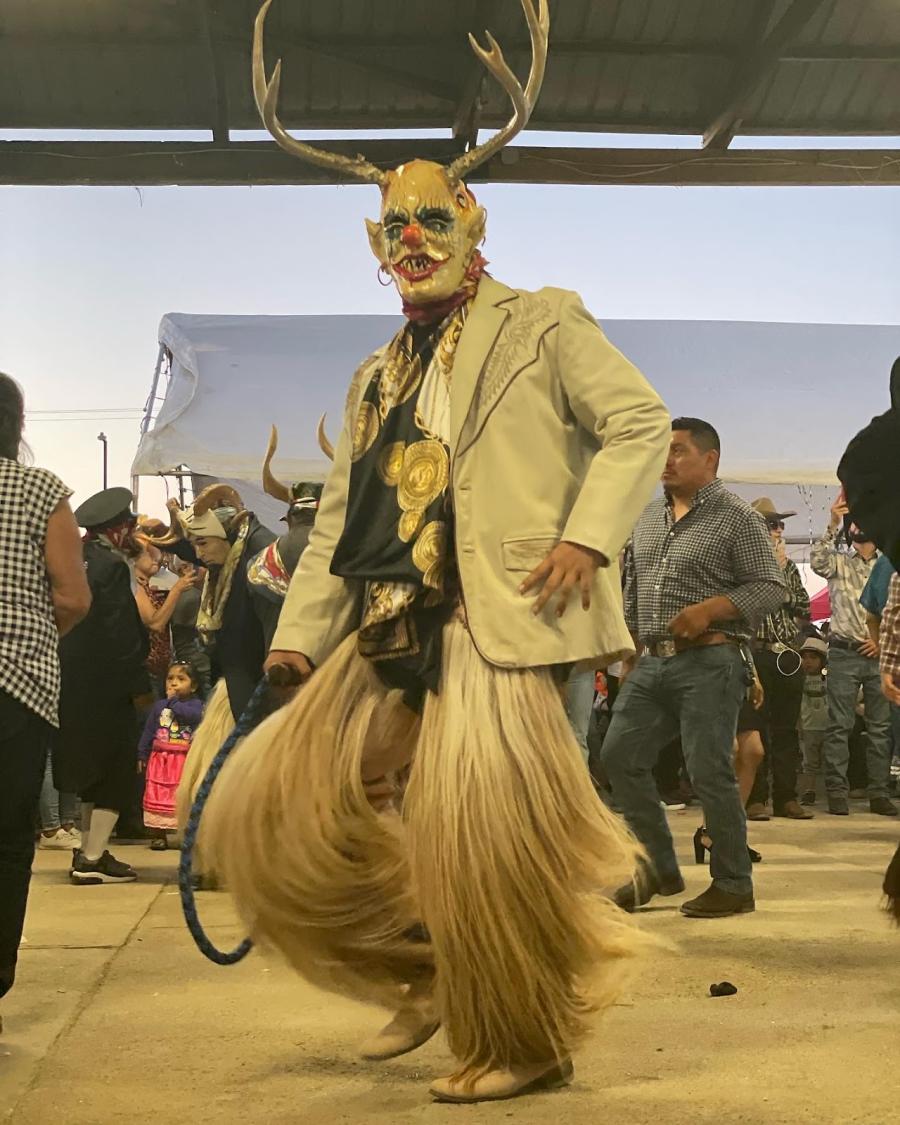

Our knowledge of “the Old Ones’’ comes to us through oral tradition—through elders but especially through our mythology. For instance, there is a sort of manic drive that overcomes many of us to acquire “wealth’’: not the kind of wealth promised in the American dream, necessarily, but the kind of wealth that was loved by the Spirit Beings in the beginning of our people. The first anthropologists wrote page after page about our unstoppable drive to seek indigenous currency: the pileated woodpecker scalps, the dentalium shell, the large obsidian blade. It is a drive that still infects us today. Young and old alike work hard to build their “treasure.’’ Once one’s treasure is sufficient, it becomes equally important to display one’s wealth at the ceremonies.

All of our traditional tribal institutions originated with the Spirit Beings. The period during which the Spirit Beings lived, our myth time, is called Pikvahahirak in the Karuk language. This was when they created our material culture, the World Renewal ceremonies, and the rituals to fix the earth. The purpose, the prayers, and the sites to be included in the ceremonies were prescribed by the Spirit Beings. Once these institutions were created, they were accompanied with instructions to humankind to enact the practices. Today, many of the original communities and their descendants continue these precontact prescriptions given to our ancestors.

Wealth is partly at the center of our Indian world. Wealth is the regalia worn during these ceremonies originating in ancient times. From the first generation of human beings, the regalia were known to be the “playthings of the Spirit Beings.’’ The playthings, ikyamiichvar (“toys” in the Karuk language), reveal to us that the ceremonial dances had strong associations with pleasure for the Spirit Beings. Today we share their pleasure, not vicariously but actually, when we perform the White Deerskin Dance, the Jump Dance, the Brush Dance, the War Dance, and other ceremonials. The regalia’s value is that it connects us directly with our primordial origins. Through this connection we experience feelings of spiritual exaltation, feelings that, in turn, are projected onto the onlookers attending the dances. And thereby, the ritual is complete.

True, the world we live in today is separated from the world of our ancestors by a gulf as big as the Pacific Ocean. Yet direct connections with that distant past persist. In some ways, the dances have evolved and reflect who we are today. Consistency with the past, nevertheless, rules.

Abalone is a Spirit Woman who is ever present during our ceremonies. The chiming of abalone pendants suspended from the ornately decorated dresses worn by the women still evokes strong feelings at every ceremony. Multistrand necklaces of abalone are worn by both the men and women. Abalone Woman transformed long ago into a form of wealth for us; our belief is that she is the feminine form of wealth. She must be present at every ceremony. She is always front and center. We cannot understand or see a day when she will not be present.

I tasted abalone meat for the first time in the late 1970s. Without a doubt, it is the most scrumptious of all the shellfish. A group of Kashaya Pomo friends brought it to a community gathering and picnic. It was great fun, but I have mostly forgotten that time except for my first experience eating abalone. It was delivered already removed from its shell and sliced into thin steaks. The cooks lightly pounded the steaks and then threw them on a barbecue grill. Another cook was deep frying seaweed until nice and crispy. The meat was placed on a homemade tortilla. Seaweed was laid across the meat. A fresh, homemade hot salsa was dribbled across it all, and this was handed over to me. I remember the moment: bright sunny day, happy people, laughing and teasing cooks, and, me, transfixed into a gourmand’s ecstasy—I love abalone!

My first experience with abalone was very positive, if a bit one-dimensional: All I ever did was eat it, so you might say that my relationship with abalone at the physical level was extremely good. About 12 years later, I discovered another side of abalone: Abalone Woman, the Spirit Woman from myth. After having met the Spirit Woman, I can say that at the emotional level my relationship with her is even better—or as good a relationship as can be had by a mere mortal with a Spirit Being.

I met Yuxtharan’asiktavaan, the mythic woman, in the early 1990s while creating a multimedia arts installation at the now-defunct, and sorely missed, Capp Street Project in San Francisco. The installation was my first large-scale conceptual art piece designed to conjure “the other world,’’ the indigenous spirit world. To be honest, Abalone Woman was not an element of the installation initially. She was not even significantly within my personal cultural consciousness at the time.

Early on, the art project became an historical de-constructivist piece. It was inspired by a six-and-a-half-minute audio recording that I had found in a catalogue of language recordings at the University of California, Berkeley. It was a recording of the last fluent Mattole Indian, Johnny Jackson. The find set off a spark of intuition, which grew slowly.

I was raised in sleepy northwestern California. I attended elementary and secondary schools that were within a few hours drive of the Mattole River valley, where Johnny Jackson had lived. I was raised to believe that the Mattole Indians were extinct. I can recall hearing distinctly from those in our household and from grade-school teachers that the Mattole were no more. It was therefore a great thrill for me to be listening to a recording of the Mattole language. What hit me hardest was the fact that the recording meant that the Mattole were not extinct. The recording had been made in 1958. Were there other Mattole Indians about?

The concept for the art installation slowly came to life and included the office and workshop of a fictitious, chain-smoking female anthropologist seeking out speakers of lost languages. In the end, she was able to gather only fragments and ghosts of what once was. Adjacent to the anthropologist’s workshop, with its maps, artifacts, filing cabinets, and anxiety, was a circular door. It recalled the round doorways at the front of the traditional plank houses of our region. Beyond the door was an interior space designed to present the sacred spirit world as it is known by the Indian people here in northwestern California. The space offered glimpses of the sacredness of the Earth as informed by the Native knowledge of the place we call home. I hoped to demonstrate that our spirit world exists well beyond the short human lifespan. I wanted to show that scientific approaches to knowing can sometimes confound, bypass, or ignore the sacred—a sacred world that coexists with the modern world and modern mind.

From the ethnographic recording, the Mattole Project was born. I learned later that the Native speaker, Johnny Jackson, had passed away a few short days following the recording. The installation’s focus shifted from physical extinction to cultural extinction to cultural persistence. I listened often to the six-minute recording of Jackson. I studied the publication by Fang-kuei Li on Jackson’s language, dryly titled Mattole: An Athabaskan Language. Though the publication is essentially a grammar, it contains a short collection of stories and texts that gave me my first look at the Mattole mind.

The installation grew sporadically—layers on top of layers of meaning. Months later, I found a very short collection of unpublished, handwritten field notes on Mattole ethnography by John P. Harrington, a noted anthropologist of his day. In 1928-29, he was busy working with my people, the Karuk, far up the Klamath River. He took a break to buy supplies and made the long, dusty car trip to Eureka on the Humboldt Bay. While there, he interviewed several Wiyot Indians about place names outside Wiyot territory. My heart rate and breathing increased as I read their data on the Mattole, their southern neighbors. The Wiyot speakers told stories associated with many Mattole sites. The fulcrum for the art piece emerged.

Speaking generally, each and every art piece that an artist makes must have a “heart’’ for it to live and to breathe. The heart for the Mattole Project turned out to be the words of those old Wiyot people. They told about a rock that sits just offshore of False Cape. “Footprints,’’ they said, were visible on top of a rock there—perfect footprints! They said the footprints were those of a Spirit Being. “Her name,’’ they said, “is Hiwot (hi:wo:t).’’ It was Abalone Woman. They also said that she was born and raised at the southern shore of the mouth of the Mattole River. This kind of specificity is almost too much, too good, for an Indian person from northwestern California to consider.

In the end, Abalone Woman, Hiwot, became the heart of the art piece for two reasons. Abalone Woman consolidated—in my mind, at least—several different stories and concepts from different local tribes that together defined northwestern California as a distinct cultural region. In addition, the voices of Harrington’s Wiyot consultants affirmed my belief and assertion that the unequivocal spiritual focus for our indigenous ancestors was a strict devotion to and emulation of the Spirit Beings, the progenitors of indigenous humankind.

There are other Footprint Rocks in California and throughout the West, and they surely commemorate important events. But this particular rock was able to combine a certain place, the Mattole River, the focus of my thinking at that very time, with the promise that has guided all of my artwork: that we have inherited certain truths about the world conveyed to us by means of our indigenous languages and myth.

One night I dreamed of a house at the center of the installation space. It was Abalone Woman’s dwelling. Her house was circled by the Spirit Beings of the world as she meditated and sang away inside the house. The dream solved for me my next Abalone problem. How was she going to fit into the piece? The dream house helped, but it also revealed a new, glaring problem: I had no abalone shells. According to the dream, her house was made of abalone shells.

I was directed by friends to a Pitt River Indian man who loved to dive for abalone. I contacted him and told him about the installation, what it meant to me as an artist, and that I hoped to create a house of abalone. He listened and then said that he did, indeed, have some abalone shells. He said I could come to his house and pick them up if I liked. I offered to pay for the shells, but he said no. The art piece made sense to him somehow, and he wanted to donate the shells. Jo Babcock, my collaborator, and I drove to Sebastopol from the Bay Area. No one was at home when we arrived, even though we had told the man that we were coming that very afternoon. There were no abalone shells. We looked and found nothing. We left empty-handed and then thought: It’s a big yard; let’s look again. As we looked here and there, we spied a black tarpaulin under a tree in the far corner. I was thunderstruck when I lifted up the tarp. There was a pile of more than one hundred fifty large abalone shells. We could not believe it. We had lowered our expectations—we might collect several shells here and several shells there. With the opening date looming, we figured we would go with whatever shells we were able to collect. The gift of the Pitt River man made it possible for Abalone Woman’s house to be of mythic proportions.

We returned to San Francisco with the shells. I cleaned them for hours and hours. Then I began designing the house according to the specifications given in the dream. It was tepee in shape. My research revealed that this was the actual shape of indigenous Mattole houses. The several ethnographic photos of Mattole houses further verified the house shape as indigenous. In the dream, the outer surface of the house was sheer. The abalone shells were within the house. Our finished structure differed slightly. Instead of sheer, the house had a hard outer shell made to resemble the rough and hard outer surface of an actual abalone shell—multicolored and rough. After constructing the house, we focused on its interior.

The shells were placed inside the structure on the floor. We added directional lighting to accentuate the shells’ natural pearly iridescence. Audio recordings of Mattole puberty songs were played on a repeating loop from inside the house, as well. The vast room in which the installation was housed was darkly lit and cool. In each corner of the room, four large, solarized, full-color landscape prints were backlit, casting light into the space. Tall wall paintings representing Spirit People ringed the room, illuminated by track lighting.

Visitors entered the space through the round door cut into the wall, with traffic naturally flowing to the right so that one circled the room in a sort of spiral course that ended up in front of the entrance to Abalone Woman’s house. As one peered through the house’s doorway, the lustrous gleam of iridescence was more impressive than I could have ever believed. Combined as they were with the visual impact of the glowing shells, the two repeating songs projected an eerie, otherworldly beauty. To this day, ten years later, I meet folks who visited the installation, commenting that they will never forget the experience.

I love Abalone.

Julian Lang is a Karuk scholar, writer, and performance and visual artist in northern California. This essay is adapted from Abalone Tales: Collaborative Explorations of Sovereignty and Identity in Northern California, by Les W. Field (copyright 2008 by Duke University Press). For more information on the book, go to the Duke University Press website at http://dukeupress.edu. For more information on the Karuk tribe, go to www.karuk.us. For more information on Julian Lang’s work, go to his website at https://www.icloud.com/.