By Diana Pastor (MAYA KI’CHE’, CS STAFF)

Mali is a diverse country where Indigenous Peoples have successfully managed to maintain cultural cohesion, but also face a number of major challenges— most pressingly, the destruction of their cultural heritage and the environment. Many of Mali’s Indigenous languages and traditional cultural practices like the Songhoi Holo horè (dance of the possessed) or the Touareg Tinafig script are little known or appreciated. The presence of Griots (guardians of the word and knowledge within Malian communities) keeps some activities alive, but many other cultural practices and touchstones, like traditional musical instruments, are disappearing.

Mali is also a mineral rich country, and mining is threatening the health and territories of many Indigenous Peoples. In the face of such challenges, there are people who are working to raise awareness to the value and beauty of the country. One of them is Georges Dougnon (Dogon), Cultural Survival’s new Capacity Building Program Assistant, who was raised in an environment where the culture and values of his People, the Dogon, were important. “I learned that every individual and every family contributes to the education of their children. Your child is my child, your friend’s father is your father, his mother is your mother,” he says.

For the Dogon, the right of the ancestors is sacred, and so is the Ginna (the lineage where the Elder is the wiseman). Georges’ parents were farmers and the relationship with the land was important. “I went to school, but I also went to the school of life, because that’s part of every child’s culture in Dogon Country,” he says. Georges’ childhood experiences inspired him to pursue a career in education. He taught for over six years in Mali and Italy, where he also completed his master’s degree in Governance, Intercultural Relations and the Peace Management Process at the University of Siena in Italy. “Education was very important to me because it allowed me to discover more than my small village, to discover the world and to learn from it,” he says.

After returning from Italy, Georges created Educ4peace, an organization that enables children and young people in his community to go to school. He also went to the United Nations to lobby for better education in Mali. He has worked in Kenya and Zambia in community engagement projects, and just before joining Cultural Survival, Georges worked in Abidjan, Ivory Coast as a consultant.

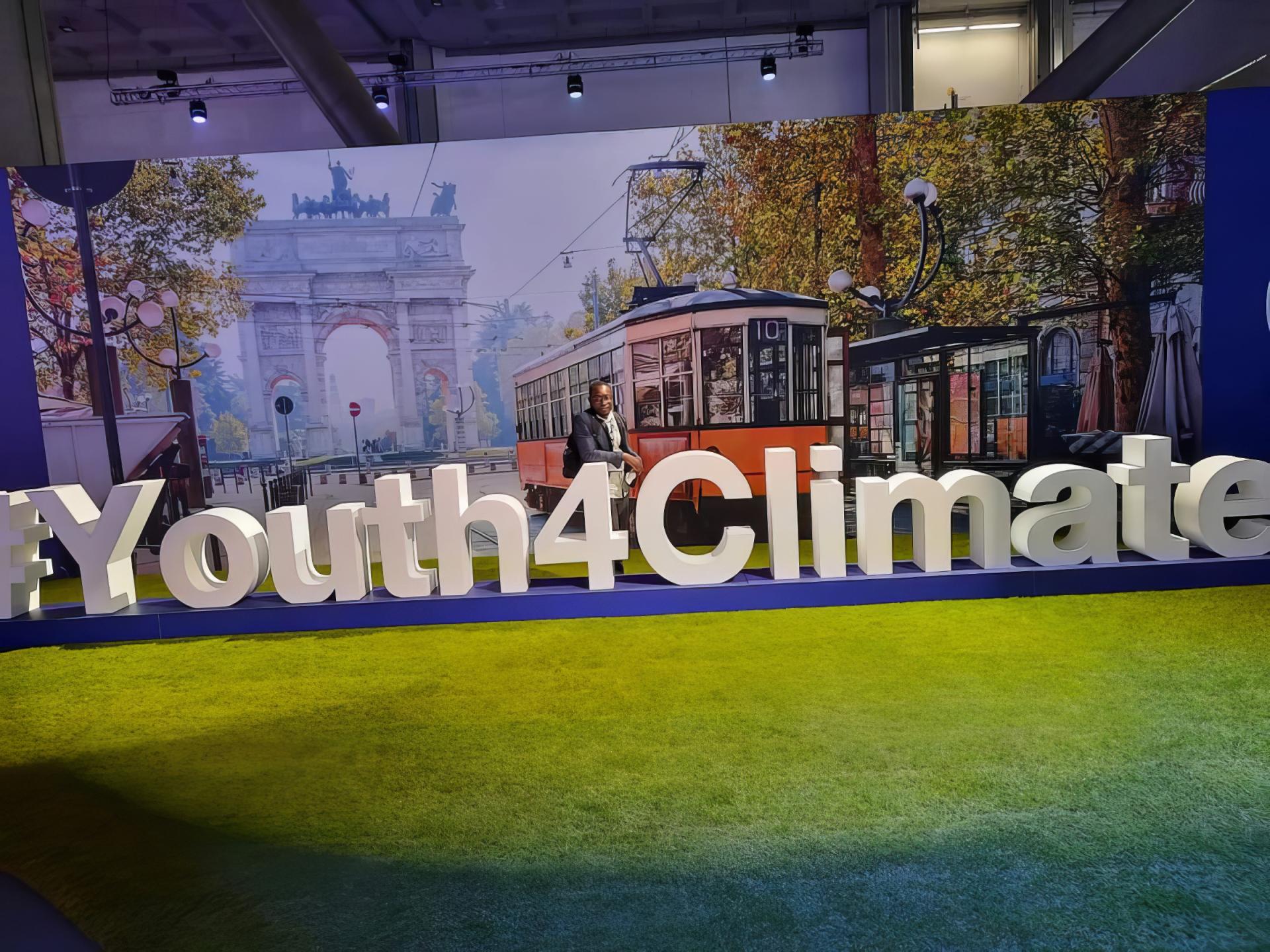

All photos courtesy of Georges Dougnon.

Georges connects his passion for education with his pride in being Indigenous. “It’s a source of pride for me to identify myself as Dogon and to show this by wearing my traditional clothes. This same pride has driven me to work to safeguard my culture, its crafts, its art, and above all, its cultural heritage. It’s not always easy to see your people facing such difficulties as terrorism or climate change. Hundreds of families have had to move and leave their land and homes to the big cities. Villages have been destroyed. But that won’t stop my commitment to showcasing the richness of my community and contributing to the resilience of my culture.”

Georges says he joined Cultural Survival because “it means living, learning, and contributing to the rights of Indigenous Peoples. I would like to learn more about Indigenous Peoples and their cultural wealth, but also from my colleagues, who are wonderful people. I want to bring my knowledge as a Dogon and receive [knowledge] from every person and every meeting.” Georges names Nelson Mandela and Amadou Hampaté Ba as two of his greatest sources of inspiration. “It was from [Hampaté] that I learned that the greatest and best school is the school of life, that each person is an inexhaustible source of knowledge. That’s why we say that an old man dying is like a burning library.” He adds, “I cannot forget Ablo Ba, my first teacher and my father, who taught me that in order to know where to go, you need to know where you’re from.”