Dr. Jessica Hutchings (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Huirapa, Gujarat) is a decolonizing researcher in the areas of Māori food sovereignty, food security, cultural and intellectual property rights, and the restoration of the environment through the restoration of Indigenous rights in Aotearoa (New Zealand.) She is actively involved with Te Waka Kai Ora (the National Māori Organics Authority) as a grower and a lead researcher to develop a tikanga-based Indigenous verification and validation system for food and agriculture called Hua Parakore. She is a founding trustee of Papawhakaritorito Charitable Trust, whose founding purpose is to deliver education, research, and practice that uplifts Māori food sovereignty and the Hua Parakore. She lives and grows food with her wife on 5.6 acres of Hua Parakore-verified land north of Wellington. Cultural Survival’s Indigenous Rights Radio Coordinator Shaldon Ferris (Khoisan) recently spoke with Dr. Hutchings.

CS: Please tell us how you got into your line of work.

Jessica Hutchings: Like most Indigenous Peoples, I’ve always had a very strong connection to the land. That’s something that I can remember in my vibration as a child. I have very strong memories of feeling really alive in the ngahere, in the bush, and being able to connect across different realms. I have a memory of wanting to be a co-creator and a co-nurturer with nature, never to work above or against her, but rather alongside her, in awe with a sense of curiosity. It’s a spiritual journey. My connection with nature and our cultural landscapes is really through my own spiritual awareness and cultural understanding of who I am in relation to our Atua (deities) and all of the personifications in the natural world.

CS: Hua Parakore is a kaupapa Māori system and framework for growing kai (food), developed by Te Waka Kai Ora. How does it differ from organic farming? What Indigenous values is Hua Parakore based on?

JH: Hua Parakore is the first Indigenous system for verifying and validating organic. In English, you can understand it as a Māori organic certification or verification system. We don’t talk about Māori organics, because organics is a Western framework and Hua Parakore is a cultural practice for us to produce food in balance with nature and in ways that can strengthen our cultural practices as Māori.

Hua Parakore produces a pure product, what our elders would talk about as a system to produce Kai Atua; that is, food from the deity, from the gods, for the gods. We’re growing Kai Atua food in its purest form, which means food in its most natural state, free from pesticides, fertilizers, herbicides, GMOs, nanotechnologies. It’s about growing food in a way that our ancestors used to grow food and reconnecting with our divine senses as Indigenous Peoples. Hua Parakore provides a decolonizing pathway to tell our own Indigenous story with regard to food production. It is important that we look to Indigenous wisdoms and solutions in a time of climate, food, and soil crises. We need to think about other forms of regenerative organic agriculture and food production and the Hua Parakore is an Indigenous pathway for doing that.

CS: Please tell us about Māori relationship with the land.

JH: The majority of Māori land has been stolen and confiscated through the violent process of colonization. Many Māori people are generally displaced from their ancestral lands, living in urban environments. We talk about tangata whenua, people of the land. This refers to the indivisible relationship between Māori and the land. In many ways I see us as the personification of our Atua, who make up our cultural landscapes. We are the land, we are the waterways, we are the deities. It’s an indivisible connection, which comes with obligations to care for and to uplift the lifeforce of all the domains of the environment.

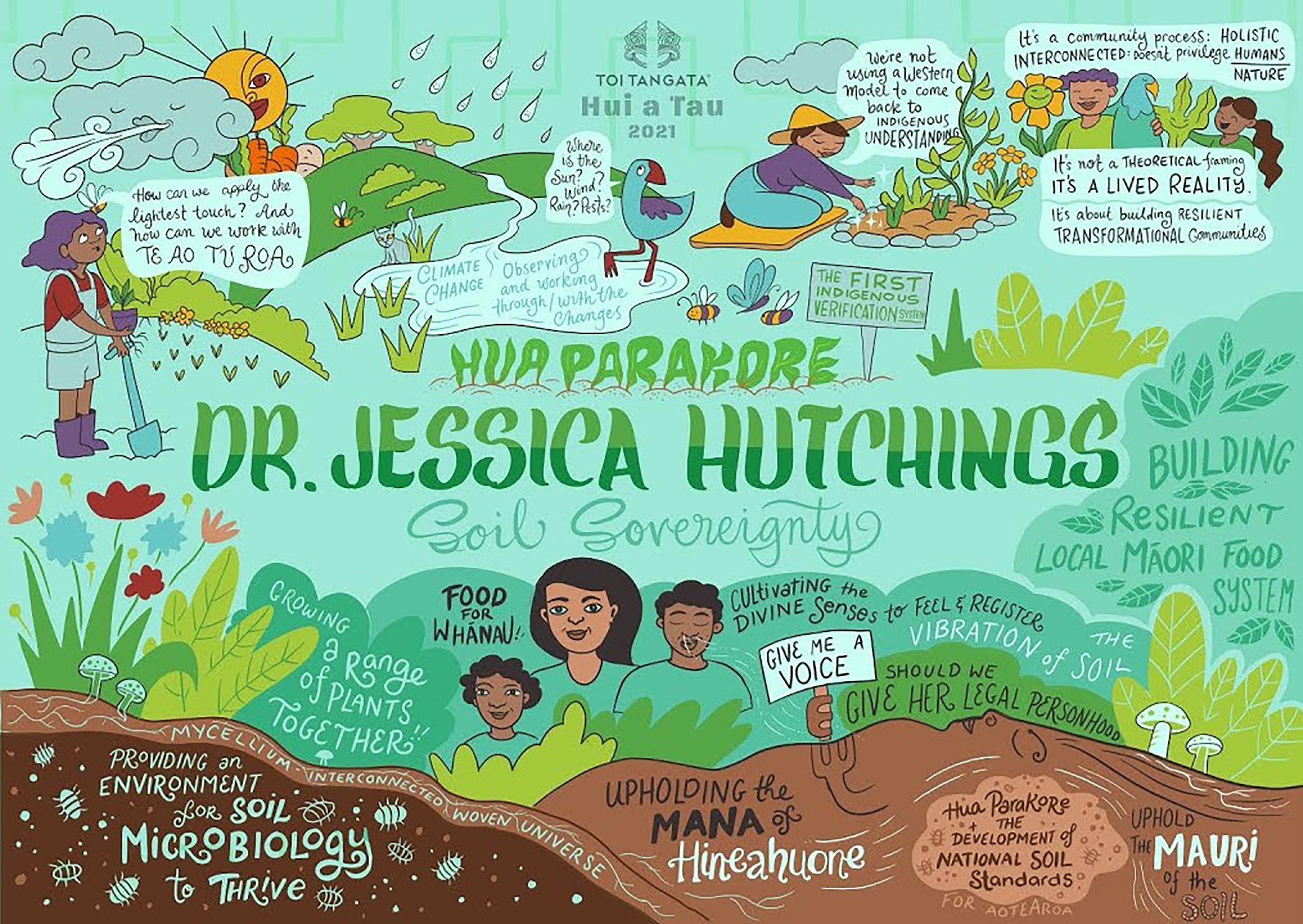

Illustration by League of Live Illustrators representing a summary of a talk given by Jessica Hutchings on soil sovereignty at the Toi Tangata conference.

CS: How was Hua Parakore developed? How prominent is it now in Aotearoa?

JH: Te Waka Kai Ora, the National Māori Organics Group, was founded in 2001 with a hui (meeting) of Māori to talk about organics, GMOs, and also the need for some way to be able to recognize Māori food production that was natural and organic but within a Māori cultural context. It’s garnered so much support since being developed; the leaders and the Elders that led this movement, who have now passed, sadly, were charismatic. They had a vision and they had a knowing that the only way to produce food was in the wisdom of our practices and mātauranga (knowledge) of our tupuna (ancestors). They also took a stand on GMOs, pesticides and herbicides, on healthy food for our people, on keeping our traditional medicines free of pesticides and chemicals. Te Waka Kai Ora started 20 years ago. In the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, the interest in safe and secure food has really peaked in New Zealand for Māori communities, particularly around organic food and around having sovereignty over our foodscapes. We’ve seen a huge increase in the movement. We just had a big online gathering where we had over 700 people interested in Māori soil and food resiliency and discussing Māori-led community-based solutions to restoring Māori food communities. I’m really inspired by what’s going on in different Māori communities around the country. They’re really diverse; some of them are working rurally and some of them in urban spaces, some of them are well funded and some aren’t. But it’s the expression of Māori people returning to grow food for our own people that is a really important turn in practicing Māori food sovereignty. This is a new discourse. For Māori communities, food wasn’t something that you heard us talk about 20 years ago. Now it’s something that our people all across the island are talking about.

CS: How do you define food sovereignty and soil sovereignty, and what needs to happen in Aotearoa for Māori to exercise their sovereignty?

JH: I often talk about Māori food sovereignty as being able to return to eat our cultural landscapes. And what I mean by that is the ability to be able to consume food within the cultural frameworks from which we come and from which we return, our ancestral frameworks. To eat our cultural landscapes means to have our food stories attached to our cultural landscape, to have thriving populations of species available for cultural harvest, and to be free from the rules and the regulations of the colonizer. Our Elders always talked about this idea that we eat with a whole Indigenous sense faculty, and that these Indigenous senses are actually our divine senses. One of the impacts of colonization has been the colonization of our senses. For many of us growing up in the cities, we didn’t grow up with lots of the traditional kai that our ancestors would have eaten. What does it mean, then, to engage those divine senses to find that we can return to eat with our Indigenous senses? Māori soil sovereignty is about elevating the mana of soil. Mana can be translated to mean prestige or authority. Māori soil sovereignty is about elevating the mana, the authority of our deity of soil of Hine-Ahu-One. It’s about speaking up for her, understanding that she’s a silent ally in our food system. It is our job to speak up and to be the voice of soil and to advocate for her. It’s about returning to understand the soil and all of her divinity.

CS: What is the role of Indigenous women in the food sovereignty movement in Aotearoa?

JH: Indigenous women are leading the movement. Indigenous women are planting gardens, sharing their love of gardening and their knowledge and expertise. But they’re also at the forefront of ensuring that biocultural power is returned back to Māori. They are advocating on a whole lot of fronts across a whole lot of political levels. [It’s important] to understand the relationship between Indigenous women as savers of seed, as repositories of knowledge to be handed down. In fact, for the last three or four years, it has only been women doing this work. So, it’s a call out to Indigenous brothers and men.

CS: What is your message to the world regarding our relationships with the land, nature, and our environments?

JH: My message would be to stop and to take a breath and think what it might be like to actually move off that capitalist neoliberal system that dominates food systems, and to think about how we can do things differently. There’s hope, and I think the hope is being able to work together with an open and loving heart as an Indigenous person.

To learn more about Dr. Jessica Hutching's important work, visit: jessicahutchings.org.

Top photo: Jessica Hutchings harvesting rongo (native plant medicine) on her Hua Parakore farm.