On September 4, 2015, following 8 months of deliberation, a crucial judgment was finally issued by the Supreme Court of Canada in the case of Chevron Corp. v. Yaiguaje. The decision unanimously recognized Canadian jurisdiction over the judgment enforcement claim made by plaintiffs representing the interests of 30,000 Indigenous persons and other residents of Ecuador’s rainforest region who have suffered the consequences of decades of unremediated toxic contamination from Chevron’s former oil operations in Ecuador.

The plaintiffs’ claim demanded compensation and reparation for Chevron Corp.’s intentional substandard environmental practices, which have destroyed part of the Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest. These claimants, organized in the Unión de Afectados y Afectadas por las Operaciones de Petroleras Texaco (UDAPT), obtained a $9.5 billion dollar environmental judgment against Chevron in 2011 and 2012, and after Chevron moved all its assets out of Ecuador, sought to enforce the judgment against Chevron assets in other countries, including Canada.

The Chevron-Texaco case (Texaco merged with Chevron in 2001) in Ecuador may be considered one of the world’s biggest oil contaminations, as it continues to affect the area where the firm operated from 1964 to 1992. The impacted area covers the territories surrounding the wells, the stations where the extracted crude was processed, and the open air pools into which the oil was directly discharged without any sort of safety mechanism. The consequences of this irresponsible conduct are contaminated water, soil, and air—the entire ecosystem.

It is estimated that Texaco, over the 28 years that it operated the sites, spilled a total of 18 billion gallons of formation water directly in water bodies at a rate close to 10 million liters of toxic water per day, along with 16,800 million gallons of crude—roughly 30 times the amount of oil spilled in the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster in Alaska. Outdated combustion techniques further resulted in 6,667 million cubic meters of gas burning off into the atmosphere. The devastating levels of contamination caused incalculable damage to the ecosystem. It also destroyed the subsistence farming and fishing of the affected people and deeply impacted Indigenous cultures.

The Canadian Supreme Court’s ruling in the case addresses two main issues. First, the Court analyzed whether and under what conditions it has jurisdiction to decide on the recognition and enforcement of the Ecuadorian judgment. Secondly, the court analyzed the existence of its jurisdiction over Chevron Corp.’s subsidiary, Chevron Canada, including questions about the potential need to pierce the “corporate veil” that separates the subsidiary and parent company.

With regard to the first point, Chevron argued that there needed to be a real and substantial connection between the Ecuadorian defendants and the Court of Ontario. The Supreme Court properly rejected this argument, confirming the generous attitude that the courts of Canada have maintained with respect to recognizing foreign judgments, considered by the Supreme Court to be crucial for the achievement of equity and justice.

Particularly noteworthy is the Court’s discussion on the concept of “universal obligation,” which is intrinsically linked to the principle of mutual respect between jurisdictions. The Court clearly intended to support the instruments of private international law and adapt them to the needs of current reality, including the speed at which modern business is conducted. In a globalized world characterized by financial transactions that quickly cross international boundaries, limiting a creditor’s prospect for seeking recompense from a multinational debtor would be unrealistic and profoundly unfair.

The Court’s decision additionally recognized the now commonplace practice of off-shoring business assets through the creation of subsidiaries in countries with more favorable legislation, with the intent of breaking up the parent corporation’s responsibility. Chevron Corp. serves as a perfect illustration of this phenomenon, with subsidiaries active in 72 countries and countless legal facades that it can rely on to confuse and evade justice. Judges have the power and responsibility to recognize when an entity is, at its decision-making core, a single entity.

Concerning the second question involving the Court’s jurisdiction over Chevron Canada, a seventh level indirect subsidiary of Chevron Corp., the Supreme Court rejected Chevron’s argument that Canadian courts would not have jurisdiction over the subsidiary because it was not party to the Ecuadorian proceeding. It is clear that Chevron Canada is party to the proceeding because it holds assets in the Province of Ontario that might be held liable to satisfy the Ecuadorian judgment. The exact nature of the legal proceedings necessary to establish a sufficient connection to seize assets remains to be seen.

Pablo Fajardo, the lead Ecuadorian attorney for the 30,000 plaintiffs, called the Canadian decision “a great triumph.” However, he wisely added, “we have more hope, but we are conscious that Chevron is very powerful and we have a lot more work ahead of us to win this long battle.” Humberto Piaguaje, afectado and executive coordinator of UDAPT, stated, “This decision is the beginning of the end of Chevron’s abusive and obstructionist litigation strategy. Chevron will now be forced to take the Ecuadorian judgment like any other, something it has desperately tried to avoid. We are confident that once Canadian courts review the fundamental fairness and strength of the judgment, it will be respected. When that happens, a measure of relief can finally come to thousands of innocent people who have suffered decades of environmental abuse at the hands of the company.”

It seems evident that Chevron and its shareholders would do better to take responsibility for the damage caused rather than continue to invest enormous sums in fighting the claim. Should the Afectados prevail against the assets of Chevron Canada, it would clarify that the “veil” allegedly protecting subsidiaries from the sins of the parents offers little protection. A final execution judgment against Chevron would also serve as the emblem of the fight against multinational oil giants generally, proving that environmental justice can be effective across national boundaries and potentially triggering a wave of new claims.

In the absence of any effective global mechanism, the Afectados will continue to seek recourse through the existing processes of cooperation amongst States and international bodies. Their struggle could be the first step toward the achievement of an integrated system for environmental civil or criminal jurisdiction where victims would be able to directly apply and effectively find relief, ideally without requiring the multiple decades of arduous litigation that have been suffered by the Afectados.

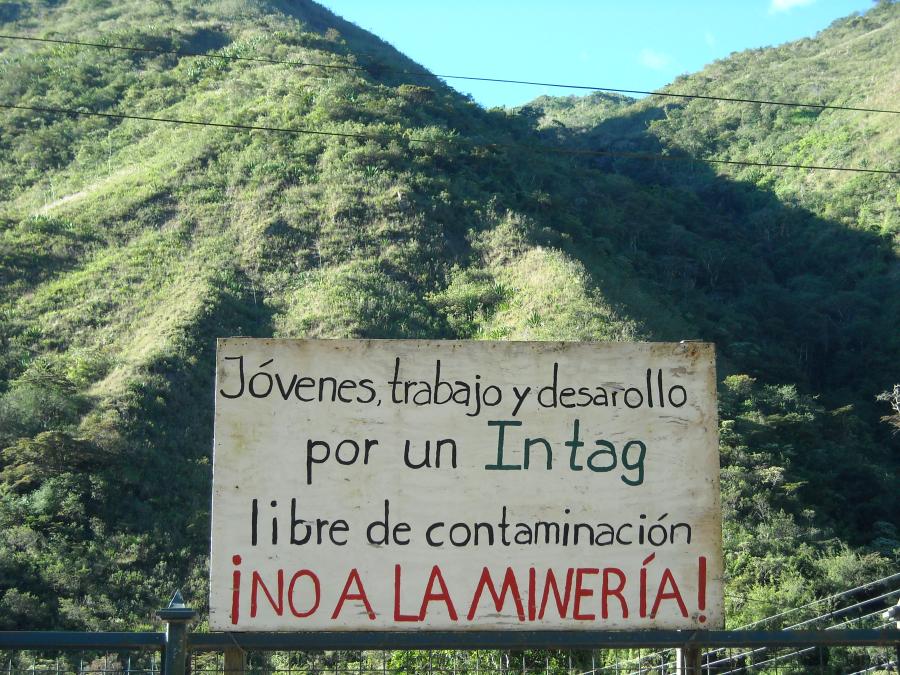

The Canadian decision is important not only for the Ecuadorian plaintiffs, but also for other people fighting Chevron where the company has committed or continues to commit crimes, as in the United States, Panama, Colombia, Suriname, Brazil, Peru, Nigeria, Angola, Belgium, Kuwait, Kazakhstan, Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines, and New Zealand. Affected communities in the Polish region of Zurawlow have opposed the exploration and exploitation of shale gas conducted by Chevron, as are Romanian people in the Pungesti region, and Canadians trying to stop the Chevron’s Pacific Trail Pipeline on First Nations reservation lands. There is truly a global community of opposition that could come together in the wake of this high profile decision and future enforcement efforts by the Afectados. “Hoy por la Amazonía, mañana por el mundo” (Today for the Amazon, tomorrow for the world) says the slogan of the 2016 anti-Chevron campaign, exactly calling for the mobilization of these communities and of the global society against impunity from the environmental crimes committed by multinational corporations worldwide.

—Anna Berti Suman is an environmental law specialist for the Unión de Afectados y Afectadas por las Operaciones de Texaco-Fromboliere.

Photo: A sample of the crude still present in the soil. Photos by Mattia Polisena.