Maricela Zurita Cruz (ChatNya) hails from San Juan Quiahije, Oaxaca, Mexico. She graduated high school with a scholarship for Indigenous women granted by the Guadalupe Musalem Fund. At the end of her studies, she began to collaborate with Grupo de Estudios sobre la Mujer Rosario Castellanos (GES Mujer), one of Mexico’s oldest women’s rights organizations, which works to improve gender equity and women’s well being through outreach, research, communications, and training in Oaxaca. During this time, Cruz worked to develop training plans and programs focused on Indigenous women’s rights and health. As a professional, she provided a gender diversity focus to the projects of Ojo de Agua Comunicación, an organization working on community communication mainly in radio and documentaries. In 2019, she collaborated with Cultural Survival as a trainer at our workshops for Indigenous women communicators held in Oaxaca.

Cruz was awarded the Mexican National Youth Award in the Social Commitment category for her work with women in her community and with GES Mujer, which nominated her. This was a great personal achievement and helped her to secure the funds needed to obtain a bachelor’s degree in education. Because she received the award as an individual, people in her community were suspicious of her “real” intentions. Over time, though, she was able to regain their trust by showing them her genuine passion for working in the community. Cruz used part of her scholarship to fund a local children’s library, which is still operating today. She has held workshops about being a new parent and made a donation to the Guadalupe Musalem Fund so that other Indigenous women would have the opportunity to continue their studies as she did.

Cruz maintained ties to her community in Quiahije throughout the 16 years she lived afar. She always knew she wanted to return, but had no idea that when the time came, it would happen so suddenly. Then, in 2020 she was unexpectedly elected by the Assembly of her community as the Regidora de Ecología (director of ecology) for a newly created municipal department. For Cruz, “having a position is not up for consideration; you have to serve.” So, when she was notified of her new appointment, she and her partner left their jobs in Oaxaca City and moved back to San Juan Quiahije.

Maricela Zurita Cruz in the field working on environmental education in her community of San Juan Quiahije, Oaxaca, Mexico.

Cruz’s appointment is a significant event in a context where power and land ownership are collective. The Assembly is the highest authority in her community; leadership roles rotate and are collectively elected. Cruz is the youngest person in the department and only the second woman to hold such a position. All positions are in service to the community, unpaid for three years, and are an acknowledgment of trust from the community in the person chosen to carry out their responsibilities.

Cruz has worked to establish her role as the first director of ecology in her community. “In the beginning, I did not know where to start, so I decided to start with the reasons why this position was created by the Assembly members: to address pollution, excessive refuse, clearing of the forest, and hunting of endangered animals as priorities,” she says. In her first year, she worked on solid waste management. The use of plastic bags in shops was banned after agreements were reached with merchants and business owners. The sale of prepackaged fried foods was prohibited. The sale of soft drinks has been regulated, and they can now only be sold in aluminum cans or family size bottles. The community also reforested some land. Currently in its second year, the department is focusing on recruiting community volunteers to implement an environmental education and awareness campaign. Much work is also being done to promote the purchase of local products and reduce garbage.

In addition to being a department head, an educator, and a specialist in gender issues, Cruz has taken on another challenging role: motherhood. Since her son was born, she has had to adjust her work and family schedules. She has had to make difficult personal decisions, such as not breastfeeding her son for all meals in order to meet her work schedules, and to cede other responsibilities to her child’s father. Cruz says that living in her community has had advantages and disadvantages for motherhood. For one, “there are always other women who help to take care of the children and practice ‘collective motherhood.’” Even at work, she says, male members of the council help her with childcare sometimes. However, she knows that the community and her family do not fully accept her parenting style, and she believes that “they would not have named me [as the director] if they had known I was pregnant.”

Cruz has also had to balance her community work and motherhood in a context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has generated great reflections and lessons for her. She has noticed that midwifery is an important area that needs to be revitalized; in Quiahije there are only three midwives, and they do not identify themselves as such due to the disregard for their work by the state health policies. On the positive side, many people who lived outside the community have returned, and are growing their own food and eating healthier. In addition, some parents reclaimed their children’s education through homeschooling, and students now have the opportunity to connect with the community and its needs, including the environment.

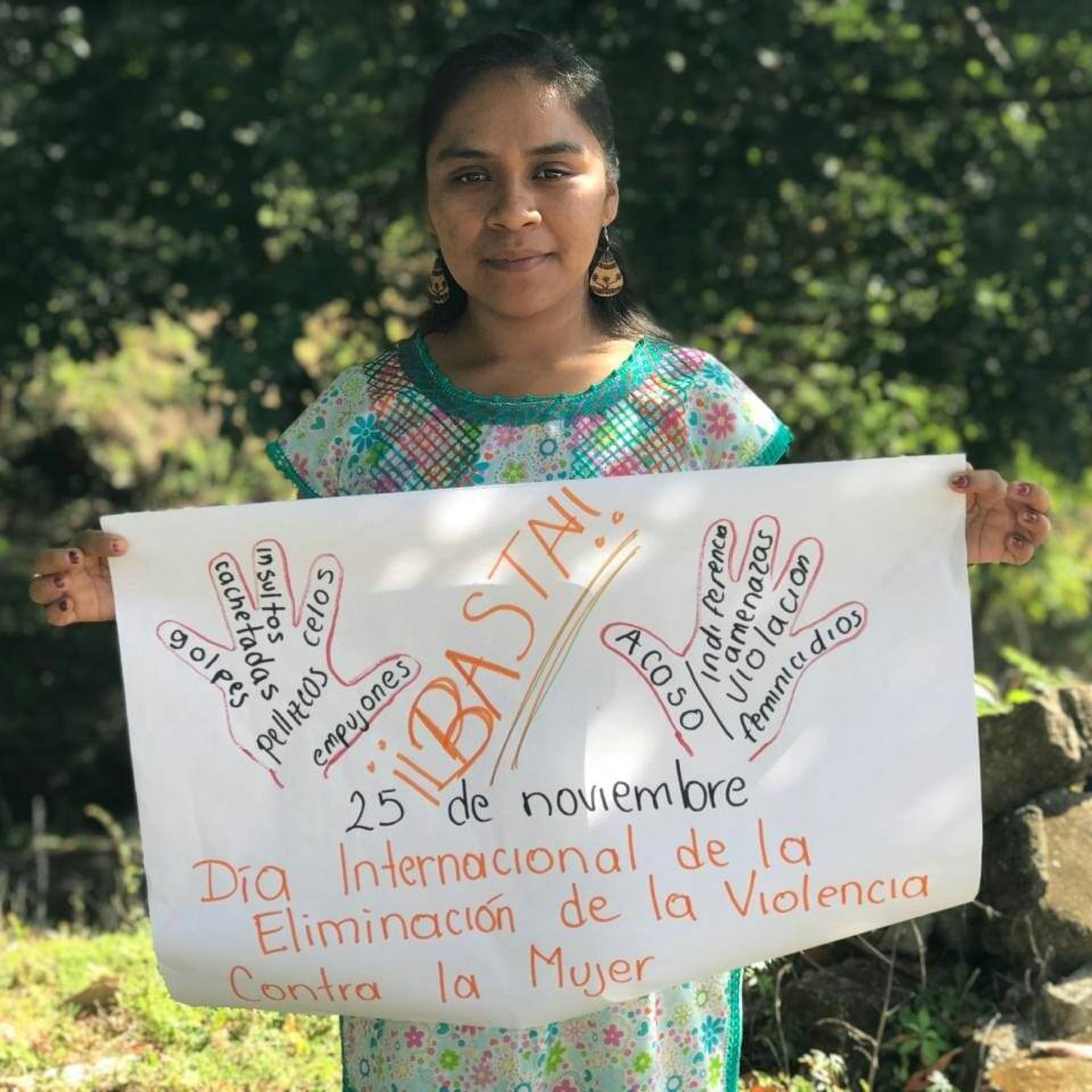

Maricela Zurita Cruz raising awareness on International Day of the Elimination of Violence against Women on November 25.

In 2019, 10 articles of the Mexican Constitution were reformed to ensure that women occupy 50 percent of political positions at all levels of government. This reform generated several internal conflicts in communities such as Cruz’s, where political positions are held mainly by men. Although many communities had made slow progress in terms of achieving gender diversity, the amendments forced a confrontation within the collective forms of government because it did not consider the different realities of gender roles in local communities. “The representative and leadership positions are comprehensive and not isolated,” Cruz says. “Gender parity has come to break this, and that is why men have rejected us. We women have to use our minds, hearts, and souls to listen to why our colleagues think a certain way. We need to understand very well the territory we are treading. We do not want to reach out to our community with the logic that we learned in the city. There is [another] way of understanding life that is important to respect.”

Like many Indigenous women, Cruz illustrates the delicate balance of maintaining all of her roles caring for her family, community, and Mother Earth, while promoting women’s participation in community governance. After working for a long time on gender issues outside of her community, Cruz believes that it is up to women like her, who begin their participation in positions of community power, to educate and make changes internally and to open the way for others. Cruz is leading by example, showing her community “that women have character, that you can be a mother and a director at the same time; that we can have a dialogue with men and women about gender problems, and take advantage of every moment to educate and make visible what we are capable of and what we can do.”

Cruz has come to believe that being a mother is a personal decision, one that should not depend on other people. “We need to put aside blame and accept that women can do many things and many others not. There are times when we need to be with our children more and we must take advantage of those moments. We must value everything that is around us and let ourselves be helped,” she says. As for other women who likewise hold community positions, “[we should] open our minds, have clear positions, and know what we are going to allow and what not, so that in moments of disagreement we do not allow things that harm us and that go against our own happiness.”

--Bia’ni Madsa’ Juárez López (Ayuuk/Binnizá) is Cultural Survival Keepers of the Earth Fund Program Manager.

All photos courtesy of Maricela Zurita Cruz.