By Tia-Alexi Roberts (Narragansett, CS Staff)

This article shares the history of Indian residential schools in Canada and the colonial violence that harmed Indigenous Nations, particularly children. The content may be upsetting. If you need emotional support, please contact the 24-hour Residential School Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419.

Throughout history, the knowledge about Native Americans has been suppressed and concealed, like a hidden secret of America. Despite the extensive history and evidence of genocide, the United States government has not made efforts to acknowledge and honor Indigenous people's history of residential schools in the United States.

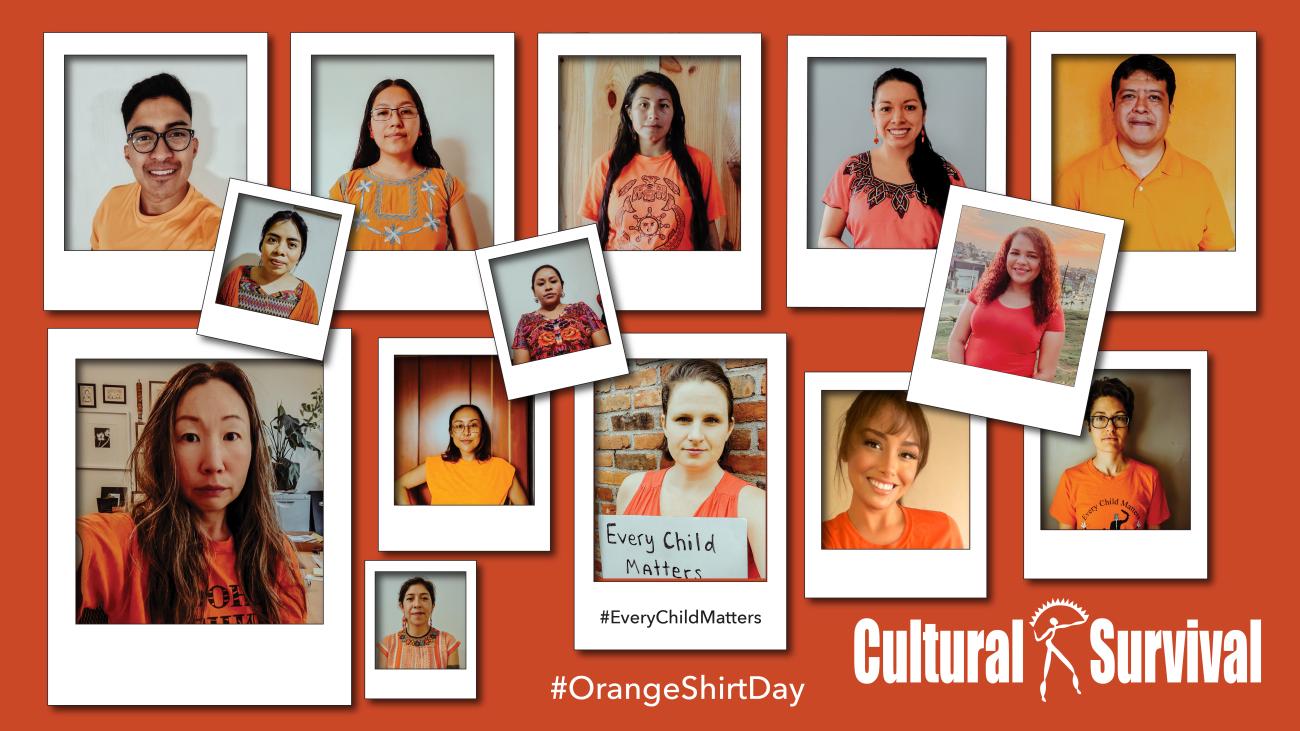

September 30 is Canada’s National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, also known as National Day of Remembrance, or more familiarly, Orange Shirt Day, established to commemorate the missing and murdered children from residential schools and honor the healing journeys of residential school survivors. It was created by boarding school survivor Phyllis Webstad (Canoe Creek, Dog Creek), whose story symbolizes the enduring connection between the color orange and her sense of insignificance and neglect.

Although it is gaining more traction, Orange Shirt Day has yet to be established as a federal holiday in the United States. To acknowledge and learn about Orange Shirt Day is to acknowledge and learn about Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island. Knowing the significance of Orange Shirt Day is vital as it deepens our understanding of the Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island, illuminates the consequences of generational trauma, honors the resilience of survivors and their families, and expands the popular understanding of the histories and cultures of Indigenous Peoples.

Many Indigenous people can attest to the fact that awareness of Native American history and residential schools is scarce. "The fact that it has been buried in the history books and not acknowledged is intentional, and in fact, the same tactics were used in New Zealand, Australia, and Canada. All of those countries have acknowledged, apologized, or reconciled in some way, except for the United States," says Christine Diindiis McCleave (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe), the great-grandchild of a boarding school survivor.

Webstad says that Orange Shirt Day and the still-missing children of the residential school era are what awakens others to the suppressed histories of Indigenous Peoples. With the growing advocacy for protective measures for Native children, Orange Shirt Day has become more prominent and has been expanding the public’s awareness of this tragic chapter of history.

The First Boarding School: Initiation of Genocide

Richard Henry Pratt was a pioneer of the Native American reformation experiment, which involved the assimilation of a group of Native American prisoners from various Tribes, including the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Comanche, Arapahoe, and Caddo. The experiment consisted of the implementation of military protocols and standards such as military-style haircuts, uniforms, drill exercises, forced use of the English language, and the establishment of a guard system where Native men were responsible for monitoring one another.

Based on the “success” of this experiment, Pratt would go on to conduct a widespread assimilation initiative in the United States in response to the perceived threat of the Native population to American settlers’ westward expansion. He persuaded the United States Army and government officials that comparable strategies could be applied to Native American children, which led to the establishment of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, the first boarding school of its kind in the United States.

To monitor the advancement of forced assimilation, Pratt hired a photographer to showcase the children’s transformation through a series of before and after photographs intended to illustrate the triumph of his ideas. Eventually, 408 Federal Indian Boarding Schools were established in the United States with the objective of total assimilation of Native American children.

Trauma/Intergenerational Impact

Many residential school survivors have reported accounts of mental, physical, and sexual abuse. Nearly all endured some form of psychological trauma, as the children were regularly subjected to constant humiliation, degradation, and verbal abuse, all of which left lasting scars on their mental well being. Forced labor, neglect, and starvation were also rampant. Students were forced to work long hours without proper rest or compensation, often engaging in exhausting and dangerous tasks. Lack of adequate nutrition and healthcare led to weakened immune systems, malnutrition, and a higher susceptibility to diseases.

Many survivors continue to suffer from PTSD, relationship difficulties, and a profound loss of self-worth as the systems implemented within these institutions ensured they were deprived of their basic needs. Even more tragically, many children died as a direct result of the mistreatment they endured. The severe trauma and mistreatment in the residential schools directly resulted in the premature deaths of countless children who were unable to escape these federally sanctioned systems.

Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA)

The brutalities of the boarding schools began to emerge after a 1928 report detailed the horrific conditions to which Native children were subjected. It still took decades for the boarding schools to finally begin closing in the 1960s, at which point, a new assimilation strategy took its place: "The Indian Adoption Project." The goal of this program was to remove Native children from their families and facilitate their adoption into non-Indigenous, Christian households. The government asserted that its objective was to encourage the adoption of children who were considered unloved and unwanted, with the belief that placing them in non-Native households would provide them with improved opportunities for a better life. Consequently, non-Native families started adopting Native American children, resulting in the removal of these children from their familial and communal ties. This adoption initiative ultimately paved the way for the creation of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA).

The Indian Child Welfare Act was passed in 1978 in an attempt to stem the Indian Adoption Project and keep Native children within Native American families and communities. ICWA is a federal law that maintains the cultural integrity of Native American Tribes and continues to be the strongest protection measure for keeping Native communities together. Prior to its enactment, up to 35 percent of Native children were taken from their families, 85 percent of whom were placed outside of their homes and Tribal communities.

While ICWA is generally considered to be positive for the Native American community, it has been challenged multiple times throughout the decades. The most recent upholding of ICWA by the U.S. Supreme Court on June 15, 2023, was celebrated throughout Indian Country as a victory for Indigenous sovereignty.

Honoring Survivors and Their Families

The celebration of Orange Shirt Day can bring peace and healing to the residential school survivors and their families. Today, the U.S. Department of Interior has identified 53 gravesites that include both marked and unmarked graves. Orange Shirt Day acknowledges the spirit of those who have passed, their families, and the cultural resilience of Indigenous Peoples. Honoring this day is also a way to move forward from the trauma of the residential school system.

Cultural Survival joins in collective calls to action for the implementation of all 94 recommendations from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Canada and the operationalization of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, particularly Article 7, which states: “Indigenous Peoples have the collective right to live in freedom, peace, and security as distinct peoples and shall not be subjected to any act of genocide or any other act of violence, including forcibly removing children of the group to another group.” Cultural Survival also joins in the calls asking Pope Francis to commit resources for justice, reconciliation, healing initiatives, and returning Indigenous lands.

There are several nonprofit organizations working to raise awareness and gain support for Orange Shirt Day and to aid survivors in healing and in pursuit of justice. The following Indigenous-led nonprofits advocate for boarding school survivors and Orange Shirt Day:

- Orange Shirt Day Society

- BC Achievement Foundation

- Honoring Indigenous Peoples

- Rising Hearts Organization

Making Orange Shirt Day an official day of observance would be an important step of allyship with Indigenous Peoples. This day offers support for survivors and their families. It highlights the effects of generational trauma that has been carried on. It is a start to reconciliation and the acknowledgment of American history.

Resources:

- The Orange Shirt Society – the organization that initiated this commemorative day and related events

- The Orange Path movement https://www.orangepath.ca

- Alaska-specific toolkit

- National Museum of the American Indian chapter on boarding schools

- American Indian Boarding Schools Haunt Many NPR Morning Edition segment

- Métis Nation of Alberta reading list from survivors of residential schools

- Whose Land is it Anyways? A Manual for Decolonization

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action

- Beyond 94 – a website monitoring progress on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action

- Reconciliation Education – online courses and films that provide comprehensive anti-racist education

- Nikki Sanchez for TEDxSFU “Decolonization Is for Everyone”

- Ginger Gosnell-Myers for TEDxVancouver “Canadian Shame: A History of Residential Schools”

- Truth and Reconciliation Week 2021 session recordings

- National Center for Truth and Reconciliation

- National Day for Truth and Reconciliation

- Orange Shirt Day: Uncovering the Dark History of Residential Schools in Canada

Actions:

- Donate to Phyllis Webstad and the Orange Shirt Society as they continue to raise awareness across the globe about residential schools

- Take the Indigenous Canada online course offered by the University of Alberta and their Faculty of Native Studies

- Contact your governmental leaders to ask what actions they are taking on the 94 Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

|

|