By Dev Kumar Sunuwar

On July 18, 2020, employees of the Chitwan National Park, led by a warden, burned down two houses and destroyed eight others using hordes of elephants to evict Chepang Indigenous families. The families have been living in Kusum Khola, in Madi Municipality-9, Chitwan district, in south central Nepal. Kusum Khola lies in a buffer zone of the park and there has been long-running tension between the park administration and locals. The Chepang People in particular have been targets of the park officials due to their high levels of poverty, discrimination and marginalization.

On July 22, Raj Kumar Chepang (24) of Rapti Municipality-2, died from alleged torture by an army patrol inside the Chitwan National Park. On July 16, Kumar and six of his colleagues including two women had gone to collect ghongi, a species of snails considered a delicacy, in the Jyudi River inside the Park. They were detained and allegedly tortured by army officials and were released the same day. On July 24, Bishnu Lal Chepang, Kumar’s father filed a complaint at the district police office, claiming that his son was tortured by the army leading to his death. The body has been taken to the Tribhuwan University Teaching Hospital in Maharajgunj for an autopsy.

These two recent attacks against Chepang Peoples are being condemned widely and have enraged the Indigenous communities in Nepal, as these inhumane actions against landless and highly marginalized Chepang Peoples take place while the country continues to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic and monsoon rains are pouring across the country.

The locals, including representatives of Indigenous organizations, are taking to the streets demanding stringent action against authorities and the army as well as compensation to victims’ families. The death of Raj Kumar Chepang and the burning down of Chepang Peoples’ houses are not isolated incidents, rather they illustrate the State’s injustice toward Indigenous Peoples through systematic attacks to drive them away from their traditional lands, territories and natural resources.

Human rights abuses by guards at Chitwan National Park were documented in a three part investigation by BuzzFeed news in 2019, which found that the paramilitary forces using violence to combat poaching are funded by the Conservation NGO the World Wildlife Fund for Nature or WWF. (Read BuzzFeed’s “WWF’s Secret War”.) Since 1967, WWF has been working in Chitwan National Park, launching the rhino conservation program in Nepal. BuzzFeed also reported that WWF continues to fund, equip, train and support officials accused of beating, torturing, sexually assaulting, and murdering scores of people, all while concealing evidence of human rights violations against some of the most vulnerable communities. The report also says that Chitwan National Park is funded in part with U.S. tax dollars through USAID.

Justice Derailed

Approximately 60 Chepang families were relocated by the local government which permitted them to build their huts in Kusum Khola area of Madi Municipality, after being displaced by flood and landslides in the hills of Makawanpur District in 2017.

The mayor of Madi Municipality, Thakur Prasad Dhakal, condemned the Chitwan National Park’s act of torching and destroying the houses and for taking action without coordinating with the municipality at a time when a municipal office was planning to manage the habitat of Chepang families residing in Kusum Khola. In Kusum Khola, Madi Municipality is building houses for landless families including the Chepang, but the park has been obstructing the local government’s initiative.

Chepang families were not living in the Kusum Khola areas by choice, but because they were told by the government to settle in the area. As traditionally nomadic communities, about 90 percent of Chepang do not own land and make a living by hunting animals and foraging for wild-roots around the forest.

According to the Chepang families, they were not given a chance to rescue their food, money, and important documents before their homes were set ablaze. “We demand that the displaced Chepang families of Kusum Khola and Raj Kumar’s families are compensated and rehabilitated immediately,” says Jitendra Chepang, Chairperson of Chepang Association, an umbrella organization of 69,000 Indigenous Chepang people, adding, “We also ask the government to provide long-term solutions to the Chepang community’s problem of landlessness. We have not been able to hold a meeting right away due to the COVID-19 situation but we are ready to go to any extent to get justice.”

Legal Loopholes

Created as the first Wildlife Conservation in 1973, Chitwan National Park covers over 367 square kilometers and is the traditional land of Tharu, Bote, Darai, Kumal and Majhi Indigenous Peoples, whose livelihood and subsistence depends upon the river and forest. They lived in the area since the time immemorial and have rich cultural history tied to the jungle and physical location of Chitwan. In 1975, the Nepali army was deployed to forcibly evicted them to create a pristine national park and has since operated with strict orders to control poaching and land encroachment. Indigenous peoples alongside Chitwan National Park have been living in intimidation and fear of being labelled as poachers, accused of illegally fishing, trapping and collecting forest products. There is no mechanism in place to file complaints against arbitrary decisions of the warden and illegal actions taken by park authorities including the army.

Chairperson of Nepal Federation of Nepalese Indigenous Nationalities (NEFIN) handing over a memorandum to National Human Rights Commission Chair Anup Raj Sharma.

The actions taken by the Park authorities violate both national and international law. The 2015 Constitution of Nepal, under Article 25, guarantees the “right to property as a fundamental right.” The existing Land Acquisition Act 2034 requires providing compensation to the acquired private property for public purpose. But no compensation was provided to the people who were displaced from Chitwan National Park.

Convention no. 169 of the International Labor Organization, a treaty to which Nepal is party, provisions under Article 28 that Indigenous Peoples have the right to compensation if they are evicted from lands where they have been living or prevented from using natural resources on which their livelihoods depend. Similarly, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in Article 10 says that “Indigenous Peoples shall not be forcibly removed from their lands or territories. No relocation shall take place without the free prior and informed consent of indigenous peoples concerned and after agreement on just and fair compensation and where possible, with the option to return.”

Likewise, Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination’s (CERD) general recommendation includes a provision for restitution on fair and just compensation to those lands of Indigenous Peoples taken without prior consent.

Since the original displacement took place in 1975, there is a slim chance of bringing a case against displacement in relation to Chitwan National Park, due to the statute of limitations strictly followed by the Supreme Court of Nepal.

Military Menace

At present, 23.39 percent of the total land in Nepal is conservation land, including 12 national parks, one wildlife reserve, one hunting reserve, six protected areas and 13 buffer zones. Indigenous Peoples have been impacted gravely in the name of these conserved and protected areas. What recently occurred in Chitwan National Park is just the latest example of how Indigenous Peoples have been victimized by conservation plans and regulations that deny them their rights over local natural resources.

Just like Chepang Peoples in Chitwan, other marginalized Bote communities, whose homelands turned into a park, lost their livelihood after the Chitwan National Park administration stopped them from collecting fish from the local river and rivulets. But Bote communities, along with others, express fear to speak about human rights violations conducted by park authorities and the army.

Similarly, Tharu Peoples living in Banke along the Bardia National Park, Magar and Gurung Indigenous Peoples residing alongside of the Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve have been targets of park authorities and they are not allowed to access local natural resources. In Manang and Mustang, local Indigenous peoples face restrictions imposed by the Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP). The local Sherpa people are left out of Sagarmatha National Park and in the eastern hills, local Rai and Limbu have the same story to share about the Kanchanjunga National Park. The state has always suppressed the voices of Indigenous Peoples through the use of the armed forces.

There are many instances of violence against Indigenous people by park officials. In July, Sunuwar Sewa Samaj, Indigenous Women’s League, Newa Misa Daboo, Nepal Tamang Women Ghedung, Indigenous Media Foundation, Cultural Survival submitted a stakeholder report to the United Nations Universal Periodic Review of Nepal highlighting the ongoing violations to the rights of Indigenous Peoples in Nepal, including rights violations in the name of conservation. In 2006, Sikharam Chaudhary, a Tharu man was beaten to death by a ranger in Chitwan National Park. A study by Lawyers’ Association for Human Rights of Nepalese Indigenous Peoples (LAHURNIP) and National Indigenous Women Federation (NIWF) from February 2020, documented several cases of killings, cases of death after alleged torture in the park, arbitrary detention, sexual abuse, harassment against local Indigenous people who wanted to use natural resources.

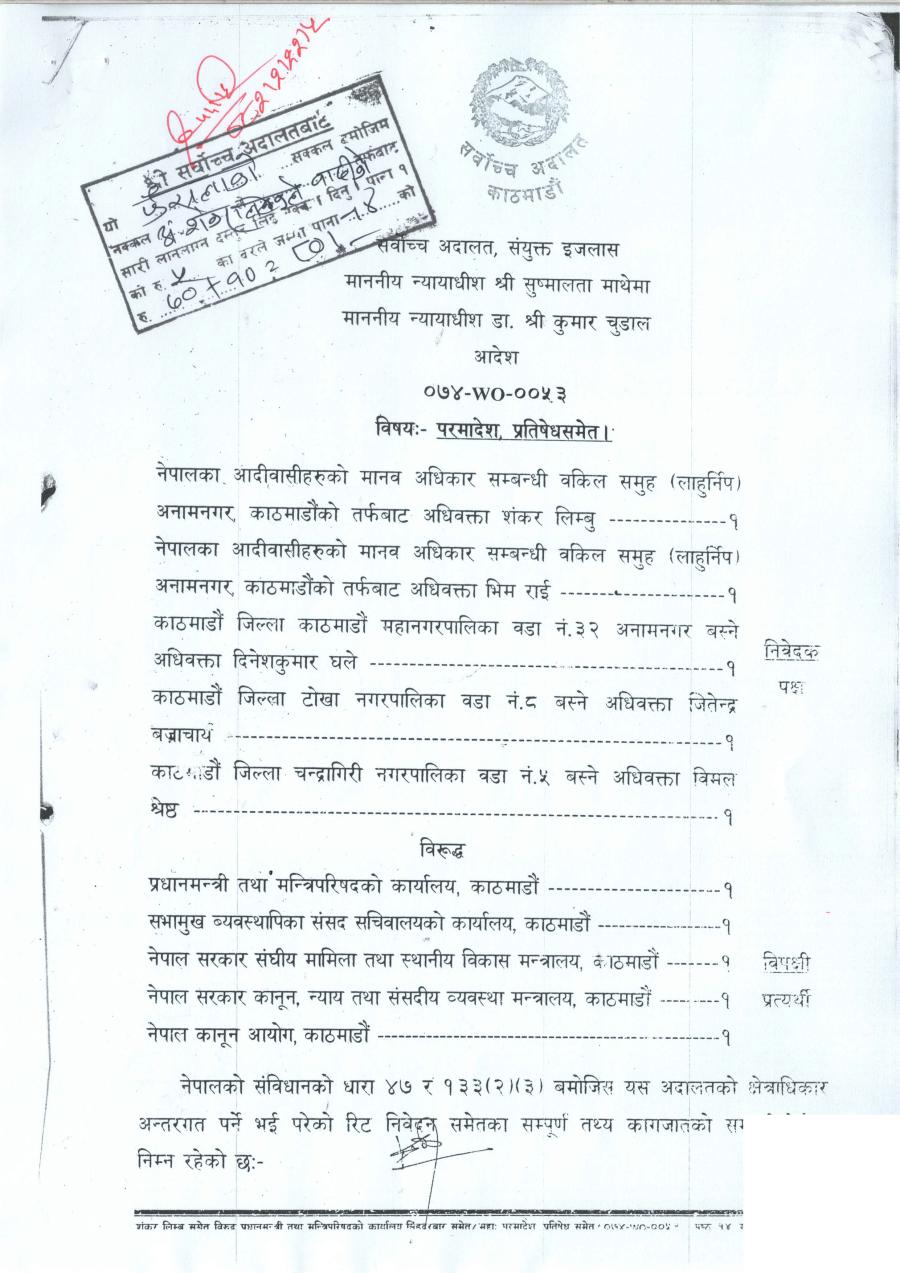

The Nepali Army stated that it has launched an investigation into how Raj Kumar Chepang was killed. Likewise, Assistant Deputy Director of the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, under the Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, apologized for the wrongdoings of the park authorities during a thematic session of the legislative-parliament committee on Agriculture, Cooperative and Natural Resources. The National Human Rights Commission also has started an independent investigation into both incidents. A group of lawyers have filed a case at the Supreme Court seeking to prevent the eviction of landless families, unless the government guarantees their Constitutional rights to housing, by providing an alternative location for settlement. But merely an apology and investigation are not a sufficient response to injustice as long as those responsible are not brought to justice.