By Dr. S. Neyooxet Greymorning

The idea of language loss is so foreign an idea for ethnocentric America that when trying to get students in my classes to gain an understanding of the impact of losing one’s language, I often turn history on its head through a conversation like the following: What if, in a hypothetical age of World War Z, you were living in a small English speaking community in Czechoslovakia when calamity hit and you were cut off from the rest of the world. Believing that this would now be your home for the next 20 to 30 years would you encourage your family and community to abandon English for the local dominant language? Over years of exposing students to this exercise, their responses were consistently “no.” Whenever I pressed the issue, by giving appropriate reasons why it was logical that they should abandon English, most gave nationalistic reasons why they wouldn’t, while others, not really knowing why, just responded that they wouldn’t abandon English. When taking this line of questioning a step even further and asking: “What if the Czech government pressured your little community to become Czech speakers; if you believed your community might be the last speakers of English would you then abandon English?” Students almost always said they would not abandon the English Language. In other words, when having no real reason why a language destined to die should be clung to, the answer students unwaveringly gave to the question: Would they abandon English, was “No.”

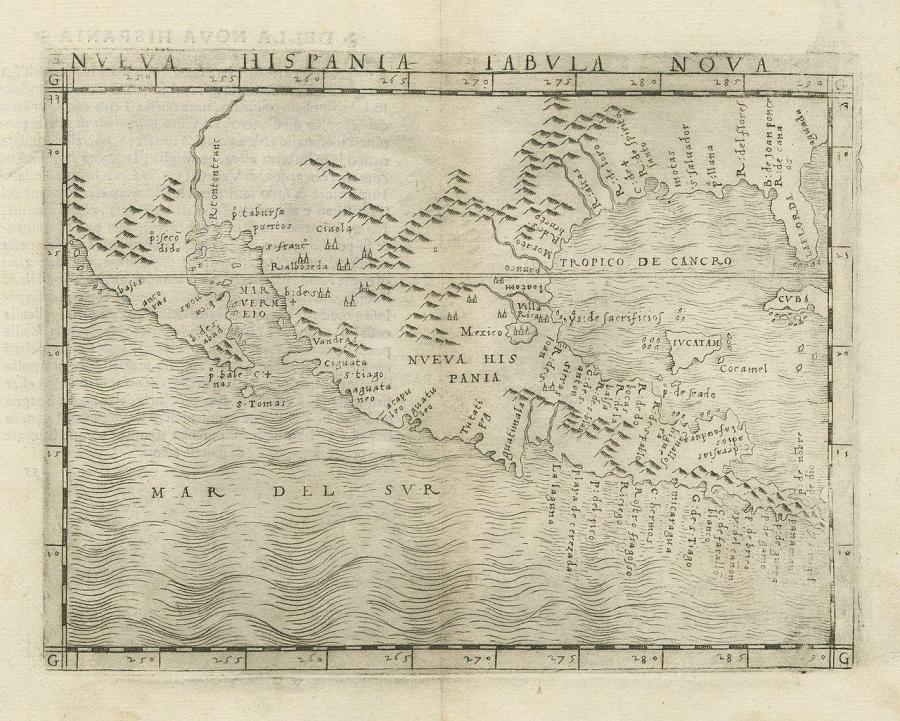

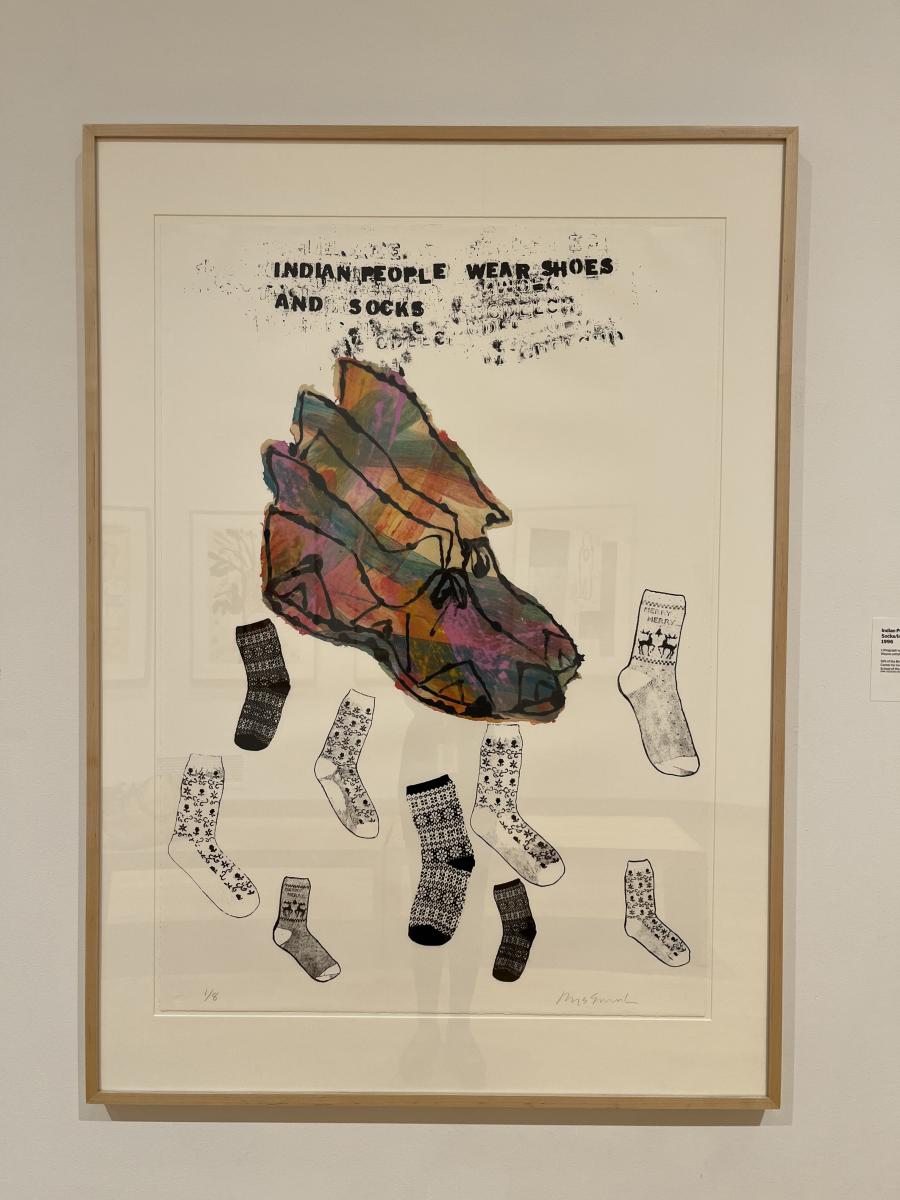

When North America was first being explored by Europeans it is said that there were over 600 distinctly different languages spoken on the continent. With his famous slogan “Kill the Indian, save the man,” Richard Pratt, founder of Carlise Indian boarding school, implemented one of the most effective weapons used to destroy Native cultures and languages in North America: the institutionalization of boarding schools. What is generally not known about the effort put into boarding schools is the amount of money spent to accomplish its goals. From the mid-1880s to the mid-1930s, in the northwest region of America (Montana, Idaho and Washington), the United States government spent over 250 million dollars in its effort to kill the cultures and languages of Indians in that region. If one were to extrapolate a figure for all of the United States it would exceed one hundred million dollars (not adjusted for today’s dollars) for that time period.

In early September 2013, I asked an archeologist what the literature was citing as the accepted population figure for Native people prior to contact. I was stunned when he told me that it was 1.2 million. When I challenged this number as being too low I was again told that this was the accepted figure. Even when I was in high school I couldn’t understand how Americans believed that prior to European contact, the Indian population, in a country rich with resources and absent of the types of diseases that plagued Europe, had never increased. Oddly, this stands in stark contrast to a European population that managed to increase in spite of its many calamities and diseases: I suppose it is better (both from historical and political standpoints) to get people to put faith in lower population figures in order to avoid the possibility of that knowledge creating psychological guilt. Having said that, however, it is worth noting that in Disease and Demography in the Americas, John W. Verano and Douglas H. Ubelaker, eds., reference Spinden’s estimates of Indians in the Western hemisphere in the thirteenth century as exceeding 50 million.

During the taking of the West, a common slogan was “the only good Indian was a dead Indian,” and many White people believed that his destruction necessitated promoting the massacre of Indians, which might explain why in the state of California the law, making it legal to kill Indians, wasn’t repealed until well after the 1900s. Richard Pratt, agreed with this sentiment when he delivered the following at the Nineteenth Annual Conference of Charities and Correction, at Denver, Colorado, in 1892: “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, and that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

When I was in middle school I learned about how some 6 million Jewish people lost their lives in Germany; it was called a holocaust. I have often wondered why we don’t learn about the holocaust that has occurred in North America.

--Dr. Neyooxet Greymorning is a professor of Anthropologyand Native American Studies at the University of Montana and serves as the Executive Director of Hinono'eitiit Ho’oowu' (Arapaho Language Lodge) in Wyoming.