Long before the arrival of the settlers, the land which we call Turtle Island was bountiful of rich foods, clean water, and a vast amount of biodiversity. Cornfields wrapped around the coastline for miles, schools of fish swam so thick, and trees were so healthy they produced many nuts and fruits. Our ancestors celebrated thanksgiving about 13 times a year. In the Northeast, the first thanksgiving is the Strawberry Thanksgiving as it is the first berry of the season. During this time, we let go of any past grudges and hardships that may be held against family and close friends. As the strawberry is the first berry of the year to bloom, we are thankful for the renewal of the Earth and the fruits that are birthed from it. The last thanksgiving celebrated in the year is the Cranberry Thanksgiving as it is the last berry of the year.

Different seasons produce different berries, fruits, and harvests that we have always celebrated. We gathered together as sister Tribes for days at a time sharing songs, stories, trade, and strengthening our kinship. Despite the historical events that have attempted to destroy our culture our Tribes still come together to celebrate the various thanksgivings throughout the year to this day. During the fall, we celebrate the harvest and call it Nunnowa, which in the Shinnecock language means “harvest time.”

The cultural views of Europeans and the Indigenous Peoples of these lands were drastically different when it came to being stewards of the land, water, and humanity. The European cultural custom of romanticizing stories through handwritten accounts created the stereotype of Native Americans of this land. One of the most famous romanticized stories throughout history is the story of the “The First Thanksgiving.” For hundreds of years, this story has painted a picture that the first settlers and the Indigenous Peoples lived peacefully and in harmony with one another. This story, unfortunately, is still being romanticized through what I call “paper genocide.” Paper genocide is a known ploy that destructs the history of Native American cultures. Many scholars, historians, and museum professionals contribute to the historical wrongdoings by publishing works that further the oppression of Native Americans. The practice of paper genocide has been done for hundreds of years and still finds its way into institutional systems today.

Ironically one of the first uses of paper genocide is the first place we see the term “thanksgiving”. The unfortunate historical significance of celebrating thanksgiving came from the celebration of the massacre of the Pequot village done by the English settlers as early as 1634. After the official Treaty of Hartford that outlawed the Pequot people from ever using their language, identifying themselves as Pequot or gathering as Pequot, Massachusetts Bay Governor John Winthrop,the day after the Pequot massacre of over 700 of my family's children, women, and men, wrote a proclamation which is known as the first written document that the word “Thanksgiving” is sited.

“Today, the 12th of the 8th Month, we, the English Protestants of the Massachusetts Bay Colony shall hold a public day of Thanksgiving to God in all of our Churches for his great mercies in subduing the Pequot…Perhaps we can now be forever free from these Pequot savages. We shall divide the few remaining prisoners amongst all of the tribes, and outlaw the Pequot out of existence. Even their names shall be wiped out of history. We are the exceptional city on the hill. We cannot allow the muck to sink us….And to commemorate this Blessed Day, the vanquishing of the horrid savage Pequot, I officially declare, hence from this day forward, for the Massachusetts Bay Colony, to celebrate annually, an official Day of Thanksgiving.” - Governor John Winthrop, 1637.

Since the day of this proclamation, the colonists that raided, pillaged, and massacred many of our ancestral villages throughout the Northeast, celebrated the day after each massacre. Historical accounts describe these celebrations to have been witnessed throughout New England, the coasts of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland. This continued for years until George Washington suggested setting aside one day per year to celebrate all of the massacres. We did not see the word “thanksgiving” again until President Abraham Lincoln wrote a proclamation with intentions in strengthening the unity of the country. We see thereafter, many other presidents continued the tradition of drafting a proclamation for Thanksgiving. Many of our Tribes on the East Coast have been paper genocided, much of this history has been covered up and many are not aware of these harsh truths.

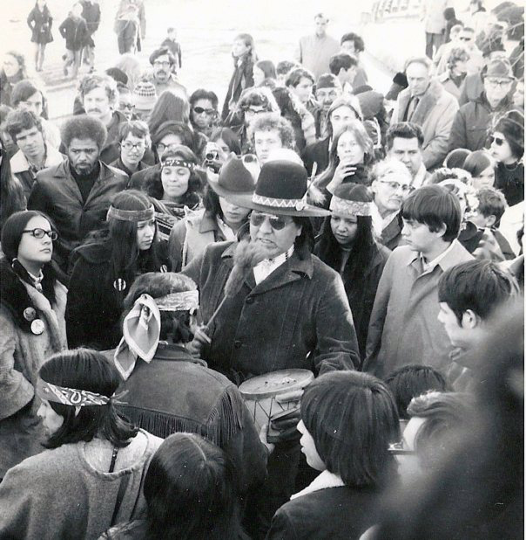

For hundreds of years after Governor John Winthrop’s Thanksgiving proclamation, our Tribes have never forgotten the celebration of our massacred ancestors and the continual attempts to erase us. In November 1972, Wamsutta Frank James, an Aquinnah Wampanoag Elder and Native rights activist, called upon his relatives to protest the celebration of Thanksgiving in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Wamsutta was uninvited to speak at a “Thanksgiving” banquet in Plymouth because the speech he prepared included the truth of what happened to his ancestors. As a result, the first National Day of Mourning began. Indigenous Peoples from all over the country showed up on the 24th of November and protested throughout Plymouth.

“How are we supposed to heal if our wounds are constantly being inflicted?” Words passed down from the late Tall Oak Weeden (Mashantucket Pequot and Wampanoag) who was one of the many Northeastern Tribal people who attended the first protest at Plymouth on the 1st National Day of Mourning in 1972. Many of our great leaders, activists, spiritual people, and community members have since passed on but what they have passed down to us is to continue to be who we are and not sit idle while the erasure of who we are continues.

As the descendants of the original protestors of the first National Day of Mourning, we have been specific instructions to never forget the day our Elders stood up to remind this country of the genocide that took place to attempt to wipe out our Peoples in the Northeast. We will continue to gather on the morning of November 24th honoring our ancestors and those who have gone before us to ensure our cultures are passed on.

Native American Heritage Month is a great time to not only learn about the history of the local Indigenous Peoples where you live, but learn how you can be a part of the social responsibility opportunities that give back to people who fight for every aspect of their existence on a daily basis.

Here are a few suggested ways to celebrate the resilience of Native American people:

- Support the local Indigenous-led events happening in our area

- Call on your representatives to Recognize Indigenous Peoples Day

- Invest in Native American entrepreneurs

- Donate regularly to Indigenous-led campaigns, organizations.

- Visit www.moskehtuconsulting.com

- Shop Indigenous created brands and support Indigenous owned businesses.

- Follow Indigenous social media accounts to learn more about the culture and Indigenous rights:

- @netooeusqua

- @warriorsofthesunrise

- @onthesite

- @Shinnecock_youth_clubhouse

- @ShinnecockPortraits

- @MoskehtuConsulting

- @IPDNYC

- @illuminative

- @Littlebeachharvest

- Check out these hashtags #StopLine3, #RecognizeIndigenousPeoplesDay, and #MMIW #PreserveShinnecockHills, #ProtectICWA

—Chenae Bullock is an enrolled Shinnecock Indian Nation Tribal member and descendant of the Montauk Tribe in Long Island, New York. She is a community leader, water protector, cultural preservationist, Indigenous perspective historian, and humanitarian. She is also the founder and CEO of Moskehtu Consulting, LLC, and a 2022-2023 Cultural Survival Writer in Residence.

Photos courtesy of Chenae Bullock.