Ben Koissaba’s “E-Learning Principles and Practices in the Context of Indigenous Peoples: A Comparative Study” focuses on how access to e-technology has bolstered the agency and global presence of Indigenous People. He draws his assertions from case studies in Australia, the United States, and Kenya.

“E-Learning” is defined by Koissaba as the use of electronic technologies to “acquire and develop knowledge that contributes to attitude and behavior change.” One of the main advantages of the E-learning approach is the ability to learn from anywhere and at any time. This approach leads to increased access to educational resources through the use of Information Communication Technology, or ICT.

Identifying the Indigenous

There is no universally accepted means of distinguishing indigenous from non-indigenous groups. The United Nations Working Group on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples were unable to reach an accord on the matter, though characteristics proposed as markers of indigenous identity include marginalization, powerlessness, and social distress. One commonly recognized definition comes from Jose Martinez Cobo, a former member of the United Nations subcommittee on Indigenous Peoples in the 1970s. He proposes that Indigenous Peoples are those communities, peoples, and nations having historical continuity with the pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories and that consider themselves distinct from the societies now predominant in those territories. The idea of historical continuity is defined by the sharing of common ancestry, general cultural manifestations, language, and residence with pre-contact societies in what an Indigenous community considers its ancestral territory. Cobo further describes Indigenous Peoples as non-dominant communities seeking to preserve, develop, and transmit their ancestral territories and ethnic identity in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions, and legal systems.

Self-identification as indigenous and recognition by a greater group is also a factor in establishing individual indigenous identity. Article 1.2 of the International Labor Organization’s (ILO) Convention highlights this self-identification as fundamental to determining groups effected by the ILO convention.

E-Learning in an Indigenous Context

The growth rate for enrollments in U.S.-based online educational institutions between 2002 and 2003 was between 10 and 20 times higher than the National Center for Education Statistics’ predictions for growth across the entire United States higher education market. Koissaba links rapid advancement in the application of technology to education with the potential for the use of E-learning as a “cultural amplifier” and “cognitive tool” to expand the dimensions of cultural communication.

An E-learning approach benefits Indigenous individuals by helping them cultivate the skills and concepts necessary in order to connect to mainstream educational opportunities, enhancing their participation in the wider global discussion, and improving their ability to shape the course of their own lives through education in order to achieve broader social outcomes. Koissaba cites a 2000 study by Dr. S Neyooxet Greymorning in noting that the past three decades have given rise to an increase in Indigenous faculty and students at institutions of higher learning, as well as the formation of the “Indigenous Humanities” through an increased offering of subjects at the college level that pertain to Indigenous issues.

Indigenous E-Learning Best Practices

Turning towards examples of E-Learning at play in Australian Indigenous communities, Koissaba describes the case of the Northern Territory Flexible Innovations Projects, which used competency navigator software to create user-defined job roles based on units of competency in a nationally endorsed qualification for Visual Arts, Crafts and Design Training package. This allowed individuals with Vocational Education and Training (VET) skills, as well as those with knowledge of institutional processes and general e-skills, to collaborate with individuals skilled in dealing with the people, processes, and operations of the Aboriginal Arts and Crafts Centers in Central Australia.

This project also gave birth to a collaborative online learning platform and social networking space aimed at facilitating Indigenous participation and education across the great geographical expanse of the Northern Territory of Australia. Teachers were able to use E-learning tools to share information with otherwise inaccessible Indigenous communities. Koissaba points to the use of ICTs and E-learning in this way as creating a gateway to knowledge and skill-sharing between both indigenous and non-indigenous communities. He also asserts that cyberspace can serve as a platform for the fair and equal exchange of Indigenous people’s perspectives, and that E-learning can be used as a counter against Eurocentric educational policy that encourages assimilation over transmission of traditional cultural knowledge and skills.

In the United States, one landmark E-learning initiative that Koissaba highlights is an online training program called “Rebuilding Native Nations” established by the The Native Nations Institute for Leadership, Management, and Policy (NNI) at the University of Arizona. The training program deals with governance and development challenges facing Indigenous Peoples and studies the action already taken by the Native Nations across Indian Country. The NNI program provides access to basic information and tools that Indigenous communities can use to improve their local governance, inter-governmental relations, justice systems, and sustainable economic development.

In addition, the Seventh Generation Fund and First People Worldwide are using E-learning strategies and social media outlets such as Facebook and Twitter in order to share intensive knowledge with Indigenous Peoples organizations and communities on a global scale. Both the Seventh Generation Fund and First People Worldwide have made online materials and grant opportunities available.

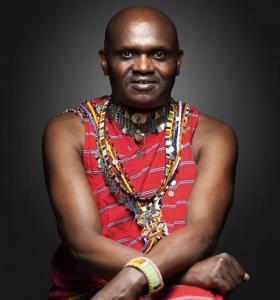

Efforts to take advantage of E-learning approaches in an Indigenous African context include the push by the Sekanani Maasai Development Project (SEMADEP) and the Mara Discovery Center to provide opportunities for Indigenous Maasai Peoples to acquire computer skills and business competency. The Maasai Mara Game Reserve is a multi-billion dollar global attraction situated on the grazing land of the Maasai people, and yet the Maasai are excluded from the profits of this venture. Through the establishment of ICT training facilities in Talek by the Mara Discovery Center and the Community Knowledge Center at Sekanani, young Maasai individuals will be able to establish an online presence and enroll in a variety of internet-based language, tourism, and business classes. This will allow the community to market private tourist camps and place local Maasai artifacts and crafts in the international market. The use of mobile devices has also granted greater financial security and independence for local business women who can now conduct their business over mobile devices.

Conclusion

Koissaba refers to research conducted by Cultural Survival when stating that interpersonal communication, accessing computing resources, and maintaining libraries of information are some of the ways in which Indigenous Peoples harness the internet to achieve community and cultural goals. Access to online resources and discussion spaces is critical for presenting Indigenous viewpoints and perspective to a wider global audience. Koissaba argues that a “systemic exclusion and marginalization” of Indigenous Peoples has occurred in the arena of education, resulting in an the “intellectual gap” between Western and Indigenous scholars that acts to suppress Indigenous knowledge and influence in mainstream policy and practice.

Indigenous Peoples have a unique array of needs and challenges when it comes to participating fully in national development and educational processes. Koissaba advocates for the creation and distribution and of E-learning techniques and materials in order to better serve the needs of Indigenous communities. Technology-based learning may help alleviate common problems such as teacher shortages and a dearth of physical learning materials while also fostering valuable skills like critical thinking, collaboration, and creativity. The establishment and integration of Indigenous Peoples’ learning centers, distance education programs, and online forums will contribute to the self-determination and global presence of Indigenous communities and help to facilitate Indigenous Peoples’ access to educational and achievement opportunities.

Click here to read the full paper: “E-Learning Principles and Practices in the Context of Indigenous Peoples: A Comparative Study”