By Sophia Mitrokostas

In 2008, Eyak became the first Native language declared extinct in Alaska. Now, with the help of the internet and a grant from the Administration for Native Americans, Eyak is also on its way to becoming the first language in the state to be brought back to life.

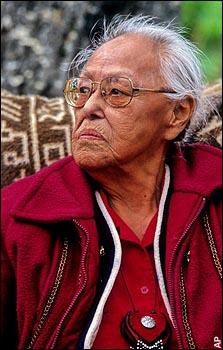

Eyak is part of the Na-Dené language family and was historically spoken by the dAXunhyuu people living along the Gulf of Alaska coast, near the mouth of the Copper River. The last remaining native Eyak speaker, Marie Smith Jones, died in 2008 and was survived by a small community of people hungry for the words they had lost.

Today, Eyak is technically classified as a “dormant” language. This means that though there are two fluent speakers of the language, there is no one who can consider Eyak their native tongue.

Neither of the current Eyak torchbearers are Eyak individuals, but they have devoted countless hours of their of their time and care to learning this threatened language. Michael Krauss, a linguist and professor at University of Alaska Fairbanks, studied and documented Eyak through much of the 1960s. His research identified Eyak as the missing link in the Athabaskan-Tlingit language family, even proving Eyak to be related to the language of the distant Navajo people.

Guillaume Leduey, a young man who began teaching himself the language as a teenager in France, is also considered a fluent speaker, translator, and instructor of Eyak.

Krauss believes that the real hope for the future of Eyak rests with the next generation. In an interview with Anchorage Daily News, he states that even if he manages to finish the work he would like to do on the language, there remains “a lifetime of work for someone to study further.”

One of the best ways to engage with the next generation is undoubtably through the internet. The dAXunhyuuga’ eLearning Place is a forum for the exchange of Eyak language knowledge. Hosted at EyakPeople.com, the site features an ever-expanding Eyak dictionary, audio pronunciation clips, and a “word request” feature that allows community members to ask for the Eyak translation of a particular word or phrase.

The site is organized and maintained by a cohort of Eyak community leaders and non-Native enthusiasts. Apart from the language direction provided by Dr. Michael Krauss and Guillaume Leduey, the project is also helmed by three descendants of some of the last native speakers of Eyak, including the daughter of Marie Smith herself.

Also involved on the technical side of things is filmmaker Laura Bliss Spaan, director of the 1996 Emmy-nominated film More Than Words. An hour-long documentary on the plight of the Eyak language and the struggle to preserve it, Spaan’s film was the first audio-visual record of spoken Eyak ever produced.

Now, the fate of the Eyak language largely rests on the determination and passion of those who hope to give the gift of dAXunhyuuga to their children. It has been over 100 years since the last Eyak children were taught their native language in their own homes, and reviving the words of their ancestors will take an immense amount of hard work on the part of Eyak community.

However, with the help of technology and the support of organizations such as the Eyak Preservation Council, The Eyak Corporation, and the Alaska Native Language Archive, this Alaskan Native language may be one of the first to rise from the realm of academics to the playgrounds and dinner tables of the next Eyak generation.

Check out Eyak language lessons, stories, and games at the dAXunhyuuga eLearning Place.