We chose not to farm everywhere. We chose to protect a certain area. We develop it for trees, and right now those trees are being cut down just because someone wants to sell charcoal,” says Robert Mutua Mila (Kamba), a Cultural Survival Youth Fellow. Presently, Kenya ranks as the 31st most vulnerable country to the impacts of climate change. Droughts and floods are causing significant disruptions to livelihoods and increasing endangerment of the environment and human lives. This year alone, there is a projected 43 percent increase in food insecurity in the country, and the resultant migration caused by drought is steadily on the rise. Deforestation and charcoal production are exacerbating this dire situation.

Mila is an eyewitness to these extreme climate changes in his country. He is part of the Motherland Project (Kamba/Gikuyu) located in Kola, Makueni County in eastern Kenya, a region characterized by an arid climate that has been severely affected by droughts and extreme floods. “We are still experiencing some change in the climate. From June to July, it’s normally the cold months. But this time we have experienced only a few cold days instead of the extreme cold that we’ve been used to. And there has been a mixture of hot days. It’s confusing how seasons are changing,” Mila says. Along with Mila, Joshua Mbindyo Mutunga, Chemitei J. Janet, Thereza Mercy Akello Onyango, Peter Kinyanjui, Elijah Muli, Ambrose Mugume, Kenneth Gitunda, and Alex Kamau are also part of the Motherland Project.

The primary goal of their fellowship project is to develop tools in collaboration with the Kamba community to address climate change and alleviate the harsh effects of drought and resulting hunger and food insecurity within the region. Mila emphasizes the link between protecting the sanctity of the land and environmental conservation, stressing the urgent need to communicate these local issues to a broader audience as an educational tool. “It is high time to tell such stories because we need to protect the land, we need to protect the motherland,” he says. “It is not only me; many people need a voice to tell such stories.”

Among the initiatives of the Motherland Project are rainwater harvesting, tree planting, cultivation of drought-resistant crops, and beekeeping. These activities integrate community education and awareness programs that aim to promote practices like water conservation and farming, an integral part of the Kamba way of life. Cassava, millet, cowpeas, and grass are alternative crops to prevent soil erosion. To facilitate these training sessions, the team of youth worked in smaller working groups, each tasked with reaching out to 50 families within the community. They also have a Sustainability Committee to assess the project’s progress. The clans represented within this Kamba community include Atangwa, Aombe, Ekuua, and Aiini. Mila describes them as “like one tree with a deep root, a tree that has many branches. A clan is a family that has many branches belonging to one lineage.”

Deforestation of the land due to resource extraction near Robert Mutua Mila’s community.

Discussing the historical aspect of land stewardship in his community, Mila says, “It is important to note that a long time ago, as the Elders tell me, people could graze without looking at the limits because the land was free and people had unity and love. With this union and love, people raised animals and had a lot of manure. The manure from the sheep, goats, and cows returned to the crops, which generated food for the family. That’s why we like to keep the culture alive.”

Mila observes birds and their organizational patterns as a model of community organization and a different perspective on land stewardship and preservation. He asks, “How can we protect our climate? How can we protect our trees with the understanding of the clan? As I experience the birds in their element, I observe the birds are free, and they know how to use their environment as a community and as a whole . . . they use every tree. They use the resources that are there equally. So, my understanding is to bring this type of thinking to the community. Our ancestors still hold the land, and why do we find ourselves in that position? Right now, we are fighting for such a resource. So it’s high time to educate the public about the birds. How do the birds live in the air? They live freely.”

This perspective permeates the Motherland Project, which emphasizes traditional perspectives on land stewardship. Their approach to preservation views spaces and human interaction as interconnected. It leaves groups of trees intact in the territory, opposing restricted preservation models like fortress conservation, which involves isolating ecosystems from human interaction. By allowing the community to autonomously map preserved spaces in the territory and use their resources in a balanced manner, similar to how birds use tree resources, the project promotes community-based conservation perspectives.

Mila is keen to instigate this perspective within his community, given that many trees have been cut down for charcoal production in a sacred space that was later designated as State-protected land. He says, “You find that where our ancestors used to pray and dance, the trees still remain. Some have been cut down. Now it’s a government-protected area, but it was supposed to be a community-protected area. We want to change that perspective, let the community feel responsible for its environment, and understand that their health depends on it. That’s what I advocate.”

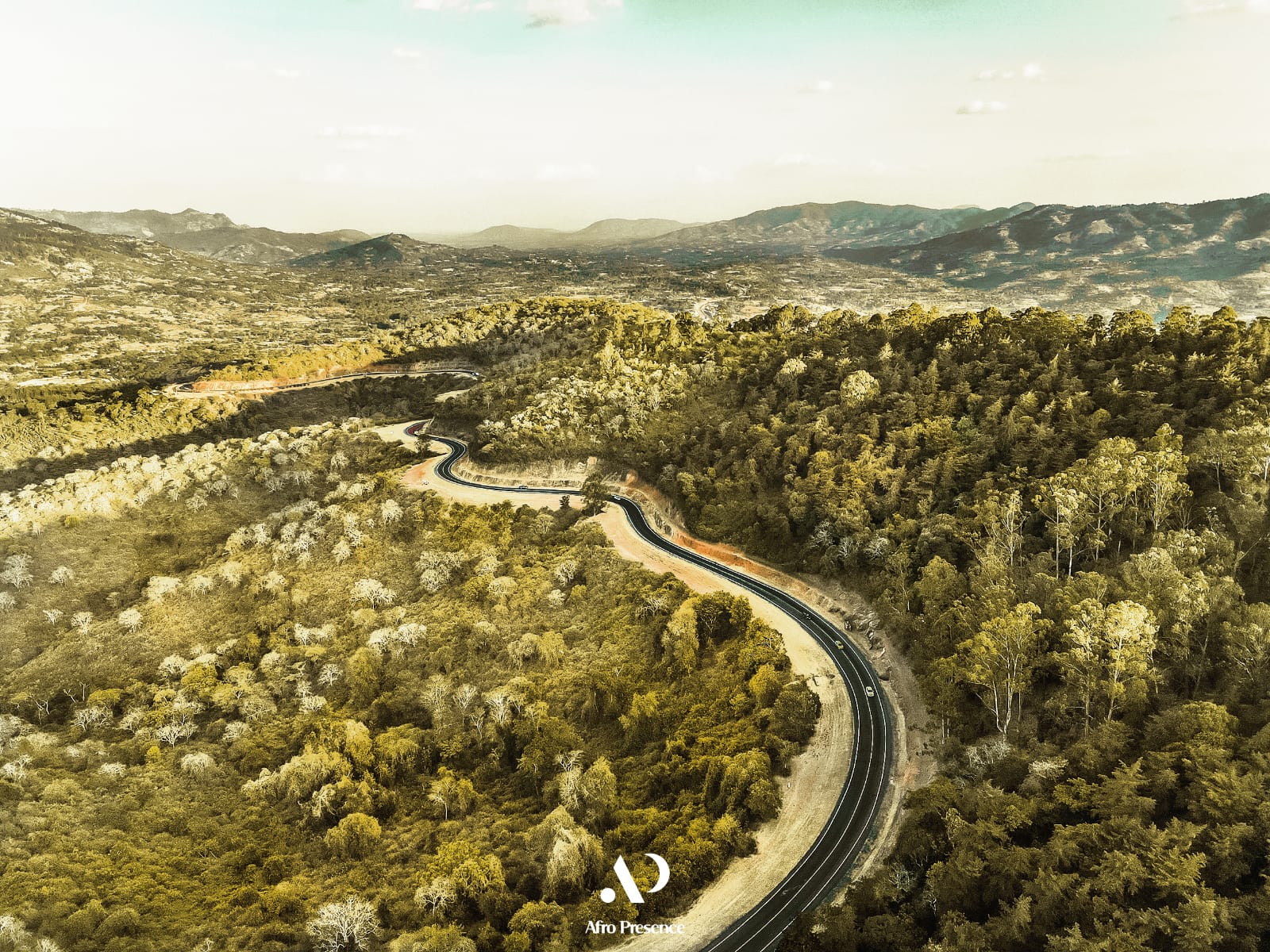

This piece of land is still intact from deforestation in Robert Mutua Mila’s community as it is under conservation protection.

The Motherland Project’s method of community land management and stewardship intersects with spirituality, in this case with a particular focus on the existence of trees and their relation to the shrines. This heritage is threatened by external cultures impacting the community, and the desperate search for alternative livelihoods has led to a shift in preservation methods. “There was a change,” Mila says. “There was a transition from us leaving the culture and adopting a new culture. People used to perform those dances and prayers; they were called here in our language of Ithembo. Ithembo was a place where people could come, perform dances, and pray to the gods, and the gods would bring back rain. But the interesting thing about this space is that it was a must for the trees to be there. Trees have an important role in our space.”

To optimize cultivation, ensure tree health, and secure drought-resistant crops through rainwater harvesting, the youth members of the Motherland Project have developed a prototype mechanism for rainwater collection located in Kivani Young Organic Farmers in Kola. Rainwater is collected from house gutters and directed to a tank functioning as a cistern. This water is intended for growing organic food and indirectly benefits beekeeping practices while maintaining the microclimate within the territory, as water, vital for tree health, ensures pollination during flowering periods. Honey production is another potential means of livelihood, and is one of the practices developed in the project, involving the training of groups of young people in beekeeping processes and the creation of modern beehives through workshops.

The Motherland Project is deeply committed to grassroots work toward stewardship practices within the territory of the Kamba community. Their primary objective is to introduce community-based conservation models by implementing practices that mitigate the impacts of climate change. These practices offer alternative livelihood and income generation for the community, thereby reducing the impact of hunger, food insecurity, and water scarcity in the region. They also plan to develop educational materials for social media and manuals for schools, highlighting the importance of and practices of land stewardship, thus opening new avenues and potential pathways for future generations.

Cultural Survival’s Indigenous Youth Fellowship Program supports young Indigenous leaders between the ages of 17–28 who are eager to learn about technology, program development, journalism, community radio, media, and Indigenous Peoples’ rights advocacy. Since 2018, we have awarded 110 fellowships supporting 204 fellows.

Top photo: Robert Mutua Mila.