In 1883, my grandfather, Saste, was a child of seven years. With his parents, he traveled in a group into the Black Hills in South Dakota for a sacred prayer journey to Washun Niye, a site from which Mother Earth breathes. They were following a path that had been a journey for his people for thousands of years. In preparation for the ceremony, the women dried the hide of a pte, or tatanka (buffalo), which was carried to this site for the sacred ceremony. The cannupa (sacred pipe) acknowledged pte by returning the hide to the world; upon completion of the prayers, the hide would be dropped into the hole. As my grandfather watched, Washun Niye carried the hide downward in a spiraling motion, soon to be enveloped into the darkness. The power of the sacred circle which has no ending was affirmed.

I heard this story in 1947, in Lakota, at the age of eight, seven years before he was to make his spirit journey—from which we all come as a spirit or soul. It took me many years to understand the importance of his story, because we must revisit anything of importance many times before we can fully understand its significance. When one finally understands, then begins the process of interpretation. The spiritual quest of truth, especially for Indigenous people, is in this process.

My grandfather and I are from a sub-band of the Teton, a member of the Nation of the Seven Council Fires. We are called the Mniconjou, or People Who Plant Near the Water. In the 1500s, one of our villages was the location of present day Rapid City along the streams of Mniluzahan Creek, or Rapid Creek, which is today’s northern gateway to the Black Hills of South Dakota. Our family has had a spiritual relationship with this special land for over 500 years.

The Black Hills were recognized as the Black Hills because of the darkness from the distance. The term also referred to a container of meat; in those days people used a box made out of dried buffalo hide to carry spiritual tools, like the sacred pipe, or the various things that were used in prayers or to carry food. That’s the term that was used for the Black Hills: they were a container for our spiritual need as well as our needs of food and water, whatever it is that allows survival.

A Legacy of Threats

The story of the Black Hills is an age-old conflict between imperialism and the understanding of their spiritual significance as a sacred site. The threats to our sacred lands began when the first two treaties were drawn up with the federal government. The first was in 1851 recognizing several tribes, including the People of the Seven Council Fires, and identified the territories of each tribe. In 1868 the Fort Laramie treaty designated an area that included the entire western half of South Dakota, with the eastern line marked by the Missouri River and a portion of North Dakota and Wyoming. We would not, as a nation, be recognized.

When gold was discovered in Montana, the trails leading to it came into the territory of the Sioux. In 1872, General Custer led a contingent of gold mining experts, theologists, and botanists into the Black Hills. Although just traces of gold were found in the streams, it was an indication that there was probably gold, veins of gold in the hills, so the US government sent two commissions to renegotiate the treaty. One of the articles stated that three-fourths of the male population had to agree to any amendments. Both commissions failed to achieve an agreement, so in 1874 Congress declared that treaties would no longer be used. Following this action (which nullified Article 6 of the US Constitution), more than 25,000 gold seekers came into the Black Hills over a very short period of time, essentially claiming that land. It’s been estimated that during that time up until 2005, when the last gold mine was shut down, approximately 500 billion ounces, or $9 trillion worth, of gold were extracted.

Problems continued in 1888 when North and South Dakota were admitted into the union and the Sioux were forced onto reservations to become US citizens. In 1876 the Sioux had wiped out General Custer and the entire 7th Cavalry in Montana, becoming the only nation to ever defeat the United States in battle. That really marked us for violation, leading to the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890. All of these things led to the people moving away from the Black Hills, away from the sacred sites for their spiritual journeys; we could no longer go back without the threat of being jailed or killed.

In the early 1920s the Sioux filed a complaint with the Indian Claims Commission alleging that the United States had illegally taken the land that had been designated to us by the treatiesof 1851 and 1868. The claim entered the Supreme Court in 1962 and took nearly 20 years to settle, enduring as the longest court case in US history. On June 30, 1980 the Supreme Court determined that the United States had indeed violated the treaty of the People of the Seven Council Fires: not just the Sioux, but the original title that we were known by. However, the federal government argued that it could not give back the land since it is occupied and includes the national monument of Mount Rushmore, a sculpture on a sacred site.

The government offered compensation—for the value of the land in 1876, prior to its occupation and the gold that was extracted, including interest—of $350 million. Of course the People of the Seven Council Fires rejected that offer. The Black Hills is a sacred grandmother to us, filled with sacred power sites. How can one sell a sacred grandmother? Now we have an opportunity to sit down in a unified way to discuss the Black Hills and the threat that is coming from ourselves as a people, as we have begun to travel the road of assimilation. Less and less people speak our native language, Lakota. Less and less adhere to the spiritual significance because of the introduction of Christianity to the reservations.

One of my fears is that there is a day coming that the Bureau of Indian Affairs will sit down at a table with the offer and our people will accept the money. At that point, thousands and thousands of years of spiritual significance of the Black Hills will be left to the wayside because the new culture of the new people that have come onto the reservation will see the same meaning in the value of the money.

Our Place in History

Recently we were asked as elders to look at some aerial photos of the southern Black Hills. We looked at them as sacred circles, and in an aerial photo we saw the image of the big dipper. This is an image of what we are, the journey of the Black Hills, the sacred journey known as “seeking sacred goodness” and the pipe that is used, the cannupa. Today the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples gives us the modern tools to stand up and declare our rights. We have come back to the table on the basis of what is recognized for Indigenous Peoples’ rights and on the basis of what sacredness is. Our beliefs are substantiated by the image of the aerial rock formations in the sacred circle that were left by our ancestors thousands of years ago.

The desecration of the Black Hills is indicative of the violation of the sacredness of who we are as a people. The insides of Grandmother Earth are being taken; the atmosphere, the area that’s there to protect us and all things is being destroyed. Earth is our grandmother, as animate as we all are, because she provides us with all of our needs to live. From the time of birth until now I look at that relationship as sacred. When our life ends here on Grandmother Earth, we become as one. This sacredness means that we walk on our ancestors. As Indigenous Peoples we are guided by the spiritualism of greater powers than we humans. We don’t seek equality, we seek justice. This is who we are, and this is where we come from.

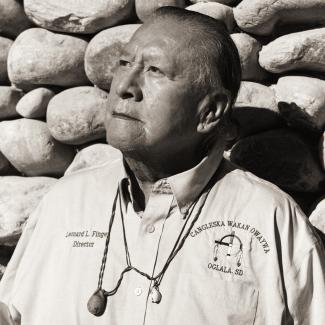

—Leonard Little Finger is a respected Lakota elder and the founder-director of Sacred Hoop School, a Lakota language school in Ogalala, South Dakata: www.lakotacirclevillage.org.