South Africa has had its fair share of colonization over the last 500 years. The first Europeans to reach the southern tip were led by Bartholomew Diaz in 1488. Not long after that, in 1510, the battle of Salt River saw the Aboriginal Khoikhoi emerge as victors after Francisco D’Almeida, also from Portugal, and his crew, attempted to kidnap Khoikhoi children and steal cattle. In 1652, South Africa was officially colonized, this time by the Dutch. Shortly after this, a pidgin, or creole, language started developing, as communication was necessary between master and slave. Afrikaans was born, and Indigenous languages started to disappear. South Africa was later ruled by the British and eventually gained independence on May 31, 1969. The apartheid regime continued until 1994, giving birth to a new era of democracy and a rainbow nation with a liberal constitution.

Having had so much European influence over hundreds of years, South Africa and its people are still caught up in a country where decolonization will be a lengthy process. Although much is being done to ensure that education is offered in many of its 11 official languages, there remain several areas where radical change needs to happen to recognize and utilize all Indigenous languages in South Africa. There are no signs of Khoekhoegowab appearing as a standard feature on restaurant menus or road signs, for example, even though this language, spoken by the Nama people, is older than all of the official languages. More and more courses are being offered in vernacular languages, and schools in South Africa are rising to the occasion by offering more subjects in languages that are now slowly becoming mainstream. Learners in some schools now can now choose official languages such as isiZulu or Sesotho as a second language, for instance. In contrast, very few efforts are underway to formalize the teaching of Khoekhoegowab in schools and universities.

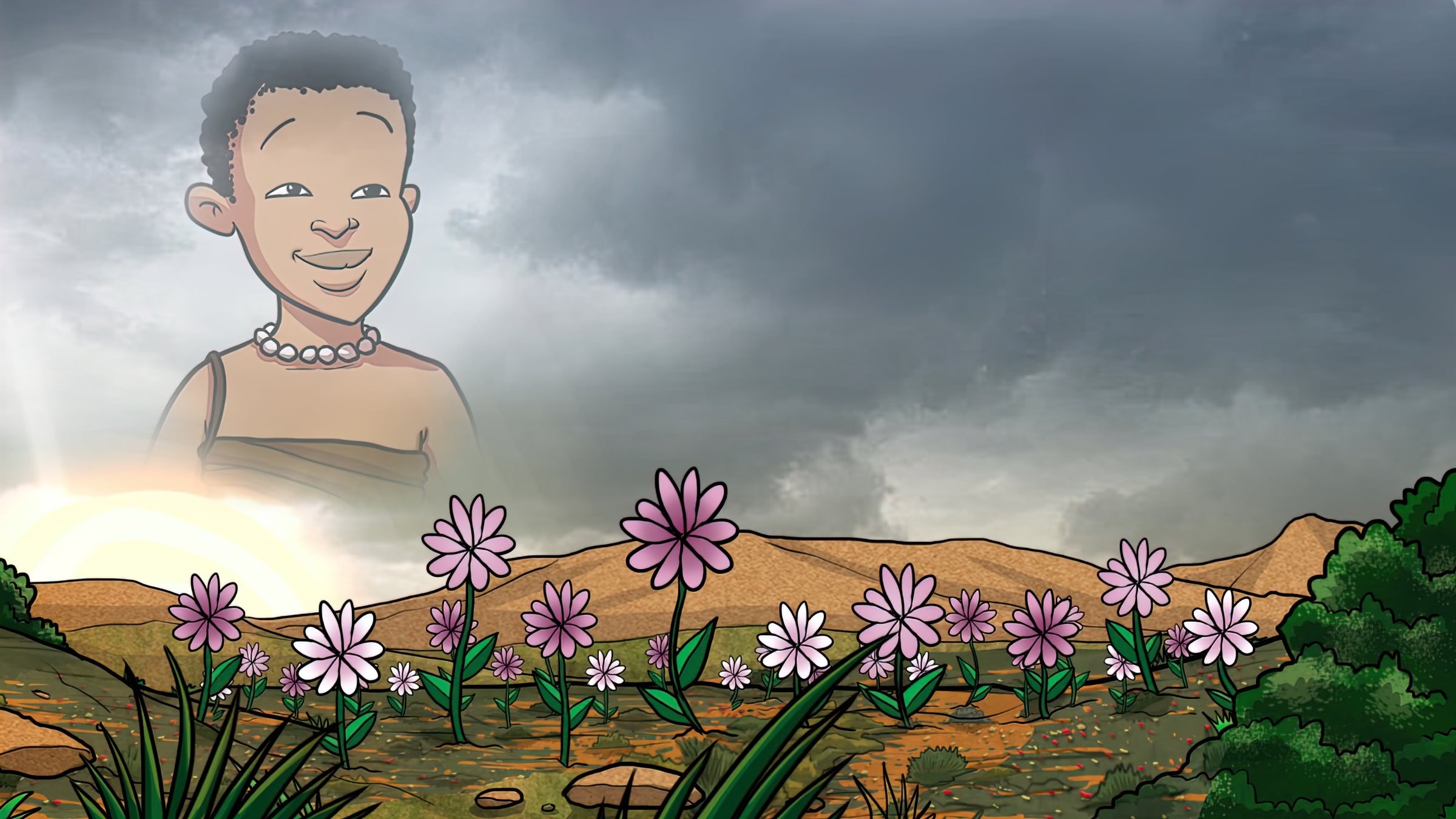

Deidre Jantjies (Khoisan), a film producer, is doing her part to ensure that more of South Africa's 35 Indigenous languages are showcased, normalized, and revitalized. She has produced a web series entitled “Stories in die Wind” (Stories of the Wind), in which she tells stories of Nama Peoples in Afrikaans with Nama subtitles. “Stories in die Wind” is a passion project from Jantjies, which tells the story of a young Nama girl born with a gift to communicate with the rain, animals, and plants, who is on a mission to find her destiny. The animated series gives a glimpse into traditional Nama life, the importance of dreaming, finding counsel in our Elders, and pursuing our destiny. Cultural Survival recently spoke to Deidre Jantjies.

Deidre Jantjies.

Cultural Survival: Please tell us about you and your work.

Deidre Jantjies: I am a storyteller and filmmaker. I’m an Indigenous cultural activist. I represent Indigenous stories of our First Nation Peoples in Southern Africa. I also used to be a flamenco dancer; that is when I sort of started understanding artistry. I’m very passionate about telling untold stories. I am originally from Oudtshoorn, which means that I come from the Outenikwa clan, but I have many other Indigenous subtribe background histories in my DNA and I am very proud to represent my Indigenous heritage. I direct documentaries, animation films, short films, and feature length films. I recently started with animation, and I’m really starting to enjoy it.

CS: Why did you choose animation as your medium for “Stories in die Wind?”

DJ: I wrote the story in 2018, and as a story it really sat with me. I initially thought that the story was going to be a theater production, but when I spoke to a friend of mine, he advised me that this is not a theater production, this is an animation. I started working on this project in 2019. I guess I specifically wrote the story because I wanted to see myself being represented. You automatically speak for a lot of voices that have not seen themselves in animation. So, “Stories in die Wind” was me tapping into a deeper sense of representation. And as time went by and I started directing, everything sort of started making sense. It became an intergenerational conversation between the older and the young people in my community and also other communities.

With regards to representation on the networks, we still have a very long way to go. It does seem that the government is starting to represent brown skinned Indigenous people and ‘coloured’ people a bit more. It is taking quite a long time. But because Indigenous people and the San are standing up and asking to be recognized, the government is starting to understand that it is important for brown skinned people to see themselves. The reason why we didn’t see much of ourselves is because we were not we were not placed into certain places and spaces. But there is a group of filmmakers and storytellers that are very serious about seeing themselves and representing their history and their cultural and traditional heritage.

CS: Most productions use English subtitles. Yours make use of Nama subtitles. Why did you make this choice?

DJ: It was an intentional decision that I had to make. When you read it, it goes by so quickly that I want people to go back and really actually engage in the dialogue of the characters. How can you introduce a language like Nama? It is in a subtle way, not too forceful, not too heavy.

CS: How do we go forward, building on efforts of Indigenous representation and making them sustainable?

DJ: We have to tell more stories. We need to make more stories and events. We need to place them into certain spaces and places. We need to become cultural in the way our work speaks for us. We need to go to these government spaces where we show our work and we talk about ourselves through our work, and show them that this is how we actually want it to be done, this is the kind of language that we want. This is the structure that we put in place for our work to be done so that the community sees this as an example. This is an example of people that are doing things the right way.

I was not prepared for “Stories in die Wind” to be created last year, so when I pitched it to Programme for Innovation in Artform Development, which is a collaboration with the Free State Festival and the University of Free State, I pitched it as a web series. They accepted it and they gave me a budget, and I made the most out of that budget so that the work can speak for itself. As soon as the work was created, it became so much easier for me to ask for funding. I got funding from the National Arts Council afterwards so that we could finalize the shortfall that we had.

It’s been overwhelming to know that people are interested in this kind of content, which is the first of its kind. It means that we really want to see ourselves. A lot of people really enjoy watching “Stories in die Wind” because it’s different. It’s simple, it’s subtle, it’s real. It’s not filtered; it’s true. And it’s been doing very well. There have been a couple of articles written on it, I have done a couple of interviews, and many other people still want to continue having conversations about it, which I’m very excited and thankful for. Last month, it played in New Zealand at the Wairoa Maori International Film Festival, which is an Indigenous film festival in New Zealand that presents Indigenous stories. If Aboriginal people from the other side of the world can see the worth in our stories, then our stories are important to spread across the world. In the international version, we will put English subtitles so that the people abroad can have a conversation about the Nama people, about Indigenous Peoples in Southern Africa.

CS: What is next for you, after the success of this animation series?

DJ: I’m working on a lot of things. I am very serious about creating feature length films and also other short films, and I am quite busy currently working on a documentary. I like this momentum. I’d like for “Stories in die Wind’’ to carry on doing well internationally and being internationally recognized. I’m also trying to figure out how we can keep the conversation going by telling more stories like “Stories in die Wind.”

The things that I received that came my way are because I prayed hard and I understood why I should be telling our stories. I understood that I had to become an activist. I had to become a storyteller because I didn’t see people like myself anywhere on television or on the internet. I also constantly heard the voice of the ancestral connection. You have to keep on believing in yourself. You have to keep speaking positive things throughout your life. You need to constantly occupy and be aware of who you surround yourself with. You need to believe in your stories and make sure that you align yourself with the right people so that they can assist you with the right direction of your story and make sure that you always know that everything that happens is for the best version of you.

All images courtesy of Dedire Jantjies.