An artist who boldly, profoundly, defies definitions: Ty Defoe can be introduced so, with the strictest parsimony for words. To explore the true breadth and depth of this young artist’s life and work so far is to encounter a rich kaleidoscope of identities, talents, and skills, each deserving its own narrative. He is a writer, musician, storyteller, hoop dancer, theater artist, and flautist. He dances the Ojibwe eagle dance, resplendent in the regalia made with the feathers he has collected since childhood, just as effortlessly as he mesmerizes a crowd in New York with a western musical piece he wrote. He won a Grammy Award in 2011 for his album “Come to Me Great Mystery.” He travels across the United States, leading educational workshops and raising awareness on themes ranging from American Indian history, ethnomusicology, food security, and climate change—a true shapeshifter of artistic expression. Defoe hails from Wisconsin with roots in the Giizhiig, Ojibwe, and Oneida Nations, and is currently in New York pursuing a fellowship on equity, inclusion, and diversity at the Theatre Communications Group.

Defoe’s forays into the art world started with dancing, which he says he learned from his mother as soon as he started walking. Then came hoop dancing. He recalls, “it wasn’t long before one of my Name-keepers gave me a willow hoop and then an iron hoop. I was a rambunctious kid . . . the balance of these two, the willow and the iron, was a way to teach me the balance of things. You weave the hoops in and out through your body. With the willow hoop you have to be gentle or it will snap and break. The iron hoop, it’s heavy and strong, and if you aren’t careful and whip it too hard, you hurt yourself.” Weaving in and out of as many as 30 hoops, transforming from eagle to butterfly to coyote, a hoop dancer uses hoops as a powerful storytelling device. As Defoe was being given the gifts of arts and perspectives by a remarkable community of family, friends, spiritual mentors, and even strangers who came to visit the reservation, he was diligently piecing them together to form an enquiry and expression of his true self. He remembers his Uncle Joey, who defied conventions and taught him drumming. He remembers his Uncle Jim who “learnt instruments by ear” and passed on that gift of music.

Eagle being his father’s clan, Defoe soon learned to shapeshift into an eagle as he danced the Eagle Dance, embodying the platonic wisdom of rising above and seeing contours of reality from a higher perspective. Rising above, bravely evolving, he found an external expression for his true identity of being a Two-Spirit.

“The concept of Two-Spirit, where the masculine and the feminine coexist in a person, has always been there among Native people; it’s just that it has been shamed and oppressed,” Defoe explains. “I have been progressively evolving. For me, changing form and name was a process I undertook to make the flow a little bit easier and help others on the same path. Being a Two-Spirit person, it’s not about a gender identity overpowering the other. The soul craves movement around these concepts of masculine and feminine we have created. Right now it’s a time for healing for the Two-Spirited community . . . there is tremendous creative potential and an amazing sense of fearlessness.”

Defoe’s own multi-disciplinary artwork exemplifies that bold creative potential, much of which he directs at exploring the structure, functions, and mutability of identities. In one of his recent musical theatre works, “Clouds are Pillows for the Moon,” he collaborated with Tidtaya Sinutoke, a composer from Thailand, to weave a story of two teenage girls—one from Thailand and another from an Ojibwe reservation— who are exploring and contesting their identities in the melting pot that is America.

Having walked the liminal world of multiple identities, Defoe feels strongly about being sure of one’s identity before spreading out one’s branches. “In the hoop of life, as you stand next to your friend, uncle, aunt, or even a stranger, you want to be just as vibrant as the other person next to you. To do that you need first know your own roots and identities,” he says. “Roots before Branches” is also the title of a show Defoe put together for the National Museum of the American Indian, which talks about such a process; his work aspires to manifest as well as facilitate that individual expression of uniqueness without cultural appropriation.

Through his experience as a Native artist, Defoe has learned the hard way that such creative spaces do not come easily. He says the traditional values of humility and shared leadership he was raised with often put him at odds with the competitive model of contemporary society that requires an artist to self-promote and surreptitiously guard his or her ideas and creations. He notes that the formulas of privilege that exist elsewhere are reflected in the world of art too: “One of the biggest challenge to art is access. There are notions about what is art, who deserves art and who has access to it. It’s often people who have power and privilege that gets to decide all these.”

Still, Defoe remains undaunted, forging new permutations of alliances and artistic expressions to counter such dynamics in the art world. In collaboration with the PA’I Foundation, he recently toured Hawai’i devising and activating community skills in the practice of art exchange. He was a founding member and artistic director of Native Punx, a venture that sought to enhance the diversity within Native and non-Native artist communities. He collaborated with The Civilians, artists in residence at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, to develop a theatrical performance titled “The Way They Lived,” which is based on the iconic piece of Native art, “End of the Trail.” He is also collaborating with Ibex Puppetry, helping develop the show “Heather Henson’s FLIGHT: A Crane Story,” for the cause of crane conservation.

Defoe aspires to create dynamic, multi-disciplinary artistic expressions for global social change and is passionate about creating inclusive platforms for people to create and access art. “I think it would be so amazing to do an art piece that goes around the world that elevates people, but also creates systemic change for underrepresented people or oppressed people, whether it be for LGBTQ, Indigenous people, or communities affected by climate change,” he says. “It is interesting, the idea of a cause. But what I want to create is something that activates people globally to activate things within themselves. Logistically that way we can create a ripple effect. Because people are different, that’s got to be done through music, through visual assistance . . . through some kind of dancing and rhythm changing. And then on the role outside, through educational pieces.” To this end Defoe plans to collaborate with digital storytelling, a project that enables the merger of different disciplines within art and help propagates potent ideas of change.

Defoe’s vision is literally a “Circle of Art,” a “Hoop of Life” that connects and engages the global community without boundaries. Having wrestled and negotiated with many stereotypes surrounding his identity, he has emerged with an authentic perspective on why a link between seemingly disparate modes, causes, and alliances is not just viable, but also necessary. As he explains, “art levels fields. It dispels the myths of a hierarchy as it allows humans to connect to each other and also to the rest of the living world, be it two-legged, four-legged, and even the elementals . . . nature, the wind. It allows us to be not just free thinkers but also feelers. It allows us to drop our masks and be ourselves. With the kind of transparency art facilitates, the world becomes such a better place.”

—Febna Reheem Caven is an independent researcher and writer on communities in contested environments.

Learn more about Ty Defoe’s art at: www.tydefoe.com.

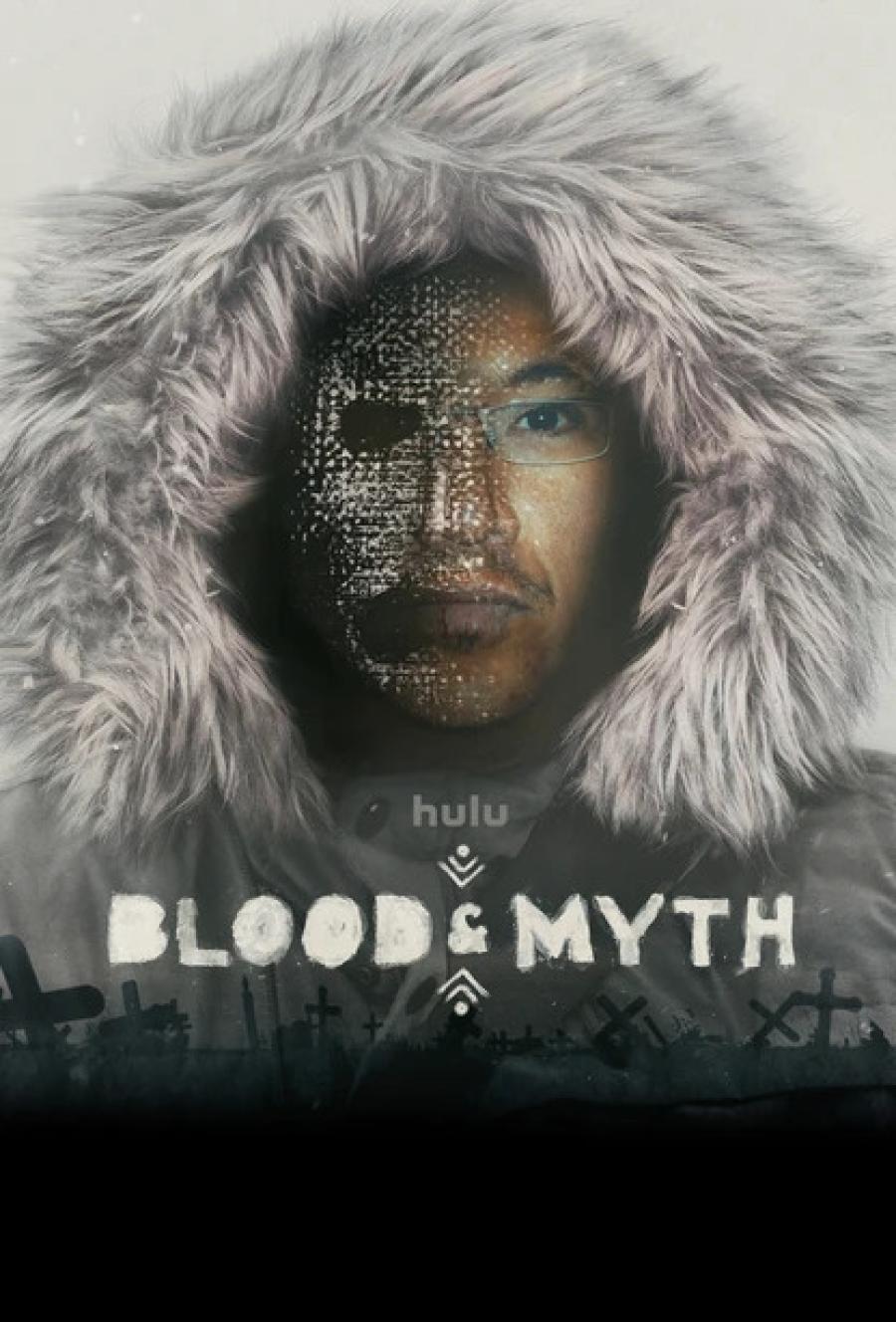

Photo: Multidisciplinary artist Ty Defoe (Giizhiig, Ojibwe, and Oneida) demonstrates his skills. All photos courtesy of Ty Defoe.