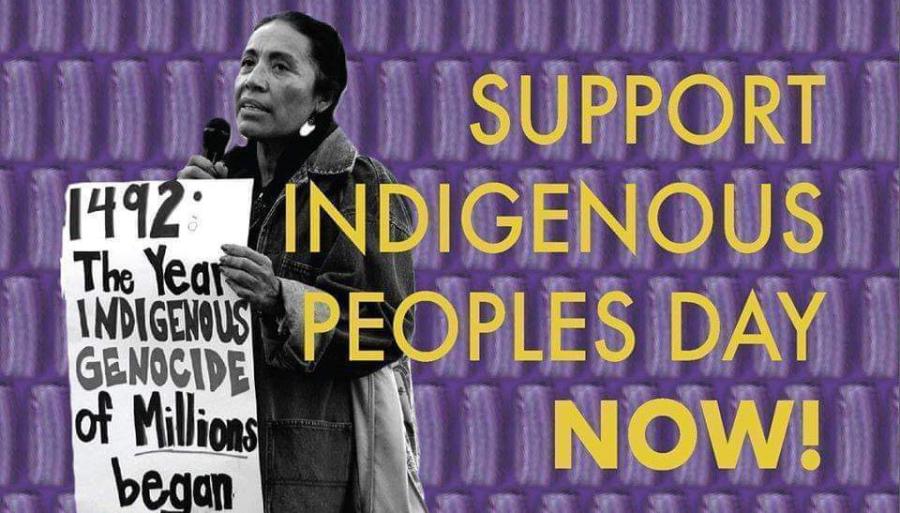

Her voice is warm, assertive, and iconic; her passionate tone and straightforward message are instantly recognizable. With an internationally renowned reputation as an Indigenous expert in international law and human rights, Mililani Trask has been advocating for the rights of Native Hawaiians and Indigenous Peoples worldwide for over three decades.

Trask comes from a long line of activists for Hawaiian sovereignty and Native Hawaiians’ rights for self-determination. “My father was an attorney and my mother was a Hawaiian. Both raised me to understand our history, the overthrow, and the loss of our lands, what happened with the Hawaiian people. That gave me a certain initiative to right those wrongs for Hawaiians, and for others as well who are in the same position,” Trask says.

For nearly 20 years, Trask was the executive director of the Gibson Foundation, a nonprofit organization that assists Native Hawaiians in attaining home ownership. She has served as a trustee at large in the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and as the interim prime minister of Ka Lahui Hawaii (the Native Hawaiian Nation) for 11 years, among numerous other roles in state and local government.

Working through and at the UN, Trask has contributed to the international discourse on the rights of Indigenous Peoples. “I started working with the UN in the 1980s with Hawaiians who were going up to represent the community interests. [In the] 1990s we were receiving word that no progress was being made at the UN level on passing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples...so I decided to go up to the UN myself to use my legal degree. When I came into the

arena, there were many other Indigenous Peoples there, and so we began work that took 22 years to pass the Declaration. One of [many] good things that came out of that work was that a strong, global caucus was built.” When the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues was created in 2002, Trask was nominated from the Pacific and served as the first Pacific basin representative. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2007, and Trask had a heavy hand in its passage.

Encouraged by longtime friend Winona Laduke, Trask has recently focused her efforts on renewable energy development projects in Native communities, especially around geothermal energy development through the Innovations Development Group (IDG), a majority-owned Native Hawaiian company dedicated to increasing the prosperity and well-being of all by developing sustainable energy resources in ways that support vital cultural traditions. The company is a model for how the Declaration can be implemented via the private sector.

“Hawaii is the most energy-insecure and food-insecure state in the Union,” Trask says. “I decided that I would work with other Hawaiians to develop a good business model so that we could look at economic development, focusing on renewable energy, in a way that would be respectful of Indigenous human rights and bring about change in terms of the development of renewable resources in Indigenous territories.”

This is how the Native-to-Native model for development was born; it is the fundamental operational guide for IDG. Trask explains: “It was established based on a belief that Native people are the best to work with other Native people because we have certain cultural affiliations. It took the heart of the Declaration, [and] using Western law, put it into a format that would facilitate protection of rights and benefits to Native peoples.”

The Native-to-Native model challenges the current approach to how energy is developed by governments where, as Trask says, Native peoples are expelled from territories, their title to their energy resources is denied, contracts are negotiated giving exclusive development rights to the company, and energy is sold at the highest market price.

“The Native-to-Native model is very different. It begins by establishing four criteria for development: culturally appropriate, environmentally sustainable and clean, socially responsible, and economically equitable. We have built into our model ways for community benefit-sharing. [For example], if you come into a community and you’re developing geothermal energy, you’re making money! You have a business opportunity and you have a product that is energy, so what do you owe that community? Number one, you owe them a share of the revenue every year.”

The model is gaining traction; the Office of Hawaiian Affairs adopted it last year. Additionally, the Hawaiian state legislature has introduced legislation requiring that there be an economic and social benefit whenever state resources and lands are being developed. The model is also being considered by the State of Hawaii Department of Hawaiian Homelands.

Though based in Hawaii, IDG has worked on projects across the Pacific, including several geothermal projects with Ma-ori in New Zealand. “We have totally shifted the paradigm. When we were first working with Maori 10 or 12 years ago, we were negotiating with folks who were developing geothermal, and they had a great deal of power. When we’d sit down to negotiate with the Maori, [the developers] would just kind of laugh and dismiss us and say, ‘you know, we don’t really do business that way. We recognize that Maori have this land, but what are they doing with it? They have sheep on it. It’s our money, our know-how, our technology… so we’re gonna give them a long-term lease and we’ll be paying them rental at the value of sheep-grazing.’ Well, we had to sort of turn that around on them and point out to them that it’s Maori who own the land. They own not only the surface with sheep on it, but they also own the subsurface resource rights. We had to point out that the actual evaluation of energy in the Pacific market, and in the global market, as set by Wall Street, is not the price of sheep. When you talk that kind of talk with somebody like Chevron, they very much change their approach.”

IDG is uniquely positioned as its management team is made up of Native Hawaiian professionals and entrepreneurs who know and understand the global energy market. They bring an extensive network of business contacts that span the financial markets of the US, as well as Asia and the South Pacific, but are first and foremost sensitive to the needs of Indigenous Peoples and devoted to the economic advancement of the communities they serve.

Trask maintains a global focus while continuing to work as a tireless advocate for policy change in Hawaii. In addition to her work with the Maori, she is working on renewable energy initiatives in Indian country that include wind, solar, and geothermal; she serves as a member of the International Indigenous Caucus on Biodiversity; and is encouraging UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee to respect Indigenous people’s rights when recognizing new World Heritage sites, among many other initiatives.

For Trask, the tasks at hand—and the urgency of accomplishing them—are clear. “All over the world we have a pressing crisis as a result of climate change…and we don’t have time to waste bickering and fighting. If you look at the Indigenous territories all over the world, you’ll see that there’s vast renewable energy resources available. So we need to move rapidly to have states, the World Bank, and others working in this area take a look at other models. “The Declaration says that we have a right to give our Free, Prior and Informed Consent. Well, that tells me we have to be at the negotiating table, we have to request disclosure, we have to ensure that consultation is meaningful. The challenge to implementing the Declaration is that we have to step into the driver’s seat. We have to say, based on protocols, what this means to have culturally appropriate development.

To learn more about the work of the Innovations Development Group and the Native-to-Native model, visit idghawaii.com.