Hiparidi Top’Tiro addresses a gathering of Xavante men to discuss ways to protect Cerrado rivers from pollution associated with the massive unregulated agribusiness. Photo by Laura R. Graham.My village, Abelhinha—Idzö’u in Xavante and “Little Bee” in English—is located in the Indigenous territory of Sangradouro, in eastern Mato Grosso, next to a town called Primavera do Leste, which is one of largest soy producing municipalities in Brazil. Big multinational companies like Bunge, Cargill, ADM, and Amaggi are also located in this area. Amaggi (an operating division of the larger Maggi company) is owned by the state governor, Blairo Maggi. These companies are destroying all of the Cerrado that surrounds our lands. They are also poisoning our rivers and our children. They fly over our lands when they crop dust, dropping chemicals down onto us from the air. This is causing a lot of illness.

Hiparidi Top’Tiro addresses a gathering of Xavante men to discuss ways to protect Cerrado rivers from pollution associated with the massive unregulated agribusiness. Photo by Laura R. Graham.My village, Abelhinha—Idzö’u in Xavante and “Little Bee” in English—is located in the Indigenous territory of Sangradouro, in eastern Mato Grosso, next to a town called Primavera do Leste, which is one of largest soy producing municipalities in Brazil. Big multinational companies like Bunge, Cargill, ADM, and Amaggi are also located in this area. Amaggi (an operating division of the larger Maggi company) is owned by the state governor, Blairo Maggi. These companies are destroying all of the Cerrado that surrounds our lands. They are also poisoning our rivers and our children. They fly over our lands when they crop dust, dropping chemicals down onto us from the air. This is causing a lot of illness.

Our lands are completely surrounded by huge agroindustry. My uncle was killed in 2003 in a fight to recoup some of our lands that are still occupied by soy farmers. There is a continuous war going on here.

Another big problem is deforestation of the lands that surround our area. Our areas are so small that it limits our access to the natural resources that we need to live. There are no animals to hunt; we don’t have the materials we need to build our houses, the leaves of indaia and buriti to make our baskets, the birds whose feathers we use for our rituals, the medicinal herbs, the fruits and roots of the Cerrado like potatoes, cara—everything is disappearing. Our diet is restricted to the foods we get from town because the land is too small for us even to plant our own gardens.

There are about 15,000 Xavante, who live in 9 separate territories all in the state of Mato Grosso. We are all fragmented now. About 60 years ago, this was all one long continuous territory along the Rio das Mortes; there was another part next to the Culuene River in the Xingu basin. We moved around a lot on zömori, trekking expeditions that lasted many months. The whole community walked together through the Cerrado, hunting many animals, because back then there were a lot of animals. It wasn’t like today, when most of the animals are disappearing because of the waradzu (non-Indigenous people). We didn’t want contact with the waradzu. We started in the state of Goias and migrated into the area that waradzu today call Mato Grosso. We crossed the Araguaia and Cristalino rivers and then crossed over the Rio das Mortes, where we settled down and were able to stay away from the waradzu until the 1930s.  Hiparidi Top’Tiro addresses a gathering of Xavante men to discuss ways to protect Cerrado rivers from pollution associated with the massive unregulated agribusiness. Photo by Laura R. GrahamThe whites made many attempts to make contact with my people, but we resisted and fought for a long time. We killed priests, a contact team from the Indigenous Protection Service, and settlers who invaded our lands. Eventually my people experienced different types of contact. My family traveled upriver along the banks of the Rio das Mortes and, in 1956, arrived at the Silesian Mission. In 1957, another Xavante group arrived. We made contact with the Silesian priests because we were being massacred and many of us were sick with waradzu diseases.

Hiparidi Top’Tiro addresses a gathering of Xavante men to discuss ways to protect Cerrado rivers from pollution associated with the massive unregulated agribusiness. Photo by Laura R. GrahamThe whites made many attempts to make contact with my people, but we resisted and fought for a long time. We killed priests, a contact team from the Indigenous Protection Service, and settlers who invaded our lands. Eventually my people experienced different types of contact. My family traveled upriver along the banks of the Rio das Mortes and, in 1956, arrived at the Silesian Mission. In 1957, another Xavante group arrived. We made contact with the Silesian priests because we were being massacred and many of us were sick with waradzu diseases.

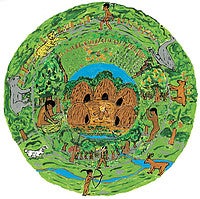

The Cerrado is where we hunt, where we harvest our foods; it is where the spirits reside and where we make our rituals. It is also the location of the Village of the Dead. The Xavante world is the ‘Ró, the Cerrado. The Cerrado is made up of many parts, which we call marã, itehudo, ambu, apê, and so on. It is all part of a single complex whole. As we go through certain rituals, we acquire greater knowledge of the Cerrado, and when we get older we have even more knowledge. But for our knowledge to continue, the Cerrado cannot disappear. How can we be good hunters if we don’t have Cerrado animals to hunt? How can we be good healers if we don’t have Cerrado herbs with which to cure? How can we be good warriors if the spirits of the Cerrado don’t have a place to stay? Our marriage ceremonies and ear-piercing rituals that transform boys into adults, all of this—everything—comes from ‘Ró, the Cerrado.

Soy agriculture is already moving into our lands because some of our relatives are under the illusion that this will bring money and improve the quality of life in the community. They are caving in to farmers’ constant pressure and don’t realize that they are being taken advantage of by the Mato Grosso state government and farmers, who only think about profits and capitalism. The government and the farmers don’t care about the Cerrado; the people, animals, our children, and the culture of the next generations are meaningless to them. I believe in taking a different approach to making money for communities.  Hiparidi Top’tiro shakes hands with Krahó men who won a log race that was part of a meeting of Indigenous leaders in São Paulo in 2004. Their meeting helped to lay the ground work for the founding of MOPIC in 2007. Photo courtesy of Sylvia Caiuby Novaes.When my family moved away from the Saleisian mission at Sangradouro and founded the community of Abelinha ("Little Bee") in 1998, we founded the Association Xavante Warã. I was president until 2007. Then my nephew Tseredzaro took over and he continues as Warã's president today. Warã's first projects were small and focused on sustainability. For example, in one early project we learned to raise bees and to harvest honey to sell. We also had a project that documented knowledge of Cerrado fruits and other flora; it focused especially on women's knowledge.

Hiparidi Top’tiro shakes hands with Krahó men who won a log race that was part of a meeting of Indigenous leaders in São Paulo in 2004. Their meeting helped to lay the ground work for the founding of MOPIC in 2007. Photo courtesy of Sylvia Caiuby Novaes.When my family moved away from the Saleisian mission at Sangradouro and founded the community of Abelinha ("Little Bee") in 1998, we founded the Association Xavante Warã. I was president until 2007. Then my nephew Tseredzaro took over and he continues as Warã's president today. Warã's first projects were small and focused on sustainability. For example, in one early project we learned to raise bees and to harvest honey to sell. We also had a project that documented knowledge of Cerrado fruits and other flora; it focused especially on women's knowledge.

We also held events in cities to bring attention to the ways that agribusiness, especially soy, is destroying the environment and threatening our way of life. In 2006 we held a protest in the town of Nova Xavantina and blocked traffic at a bridge over the Rio das Mortes that many trucks use to carry agricultural products to big cities. Xavante filmmaker Caimi Waiassé made a film about this protest that has just been released.

When I was president of The Xavante Warã Association in 2005, we invited our relatives, the Krahó, to join us in an event in São Paulo, and we realized that Indigenous Peoples must unite to protect our future and the future of the Cerrado. This inspired us to create MOPIC, the Mobilization of Indigenous Peoples of the Cerrado.

MOPIC works to bring visibility to Cerrado peoples and to create dialogue between Indigenous leaders. It supports groups that are pressuring the Brazilian government to fulfill its legal obligations to Indigenous lands and peoples, and it facilitates interactions between Indigenous Peoples and nongovernment organizations like Cultural Survival. It also encourages sustainable projects and activities that promote appreciation of Indigenous culture in and outside of our communities.

Since its founding, MOPIC has held two big events. Our first General Assembly took place in December 2007. More than 200 people from 25 Indigenous groups from 5 different states came to Aldeia Cachoeirinha in the Terena Indigenous Territory in Mato Grosso do Sul. We talked about the environment and health care and especially about conflicts with landowners and the persecution of Indigenous Peoples who defend their lands. We issued a statement denouncing the imprisonment of Indigenous leaders, the high incidence of Indigenous suicide in this state, and government plans to build 43 biodiesel plants in Mato Grosso do Sul that will worsen conditions for Indigenous Peoples. We also called upon FUNAI to finalize land disputes.

Leaders from 24 different groups attended the second meeting in December 2008 in Aldeia Ngojwere in the Xingu National Park. Our focus in this meeting was soy agribusiness and the impacts of hydroelectric dams. We demanded that the state abide by ILO Convention 169; called for a halt to hydroelectric construction projects in six different river basins and for a halt to barge traffic on the São Francisco River; and called on the state government to support further organization of indigenous peoples and for additional Indigenous representation at the federal level.

Our next big meeting will take place in November 2009. We will be talking about proposals to unite some Xavante areas into a contiguous territory. We have a lot of work to do. I am happy because we are getting stronger as more Indigenous groups join our network. I am also encouraged that so many youth are committed to our struggle and to helping us become even stronger.

Hiparidi Top’Tiro is a Xavante Indigenous leader from the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Since 1996, through the Xavante Warã Association, he has been fighting against the advancement of agrobusiness in and around Indigenous lands in the Cerrado. In November of 2006, he assumed leadership of the Mobilization of Indigenous Peoples of the Cerrado.