Until the advent of synthetic pigment production in the 19th Century, paint pigments were either mined, gathered from plants, or processed from animals. As society becomes more aware of the toxicity and health impacts from synthetic paints, an increasing number of artists are returning to processing their own natural pigments. Indigenous artists are leading the revitalization of natural pigment production through traditional artistic processes, applying their values and honoring their kinship to land and all living things. Cultural Survival spoke with three Indigenous artists about the revival of this art and cultural practice and the resurgence movement to ensure the continuity of land-based natural pigment processing.

Vivianite pigment inside a petrified sitka spruce cone. Photo by Camas Logue.

Camas Logue (Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin):

Waq lis ?i gew ?a seesas Camas Logue. I am an enrolled member of the Klamath Tribes and belong to the Klamath, Modoc, and Northern Paiute. I am living with my wife and family in the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community in northwest Washington.

As a multidisciplinary Native contemporary artist, I work with the traditional weaving and carving techniques taught to me by my Elders. I’m also an illustrator, printmaker, woodworker, and musician. My primary language is oil painting. The pigments in paint are made up of minerals and earth. As a fluid medium, paint is governed by the same geological processes as the land. I’m interested in representing the dynamic events that occur at the Earth’s surface, using materials and actions to mimic natural forces— seismic shaking, wind, moving water, freezing, and thawing. Through layered pigments and applied process, I encourage the painting’s surface to experience deformation, translocation, or chemical reaction. I believe we can see the connections between ourselves and everything around us by learning to read the patterns in the land.

Sarah Hudson (Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Pūkeko, Ngāi Tūhoe):

I live in Whakatāne, Aotearoa with my family. Whakatāne is Ngāti Awa land, so I live where my ancestors used to occupy. I live on stolen, confiscated land (by the Crown), which was then resold for generations. I’m an artist, a mom, and a researcher. I have been a practicing artist for about 10 years, working with earth pigments for about a year and a half. But land has always been a major theme through my work [and] all Māori people’s work.

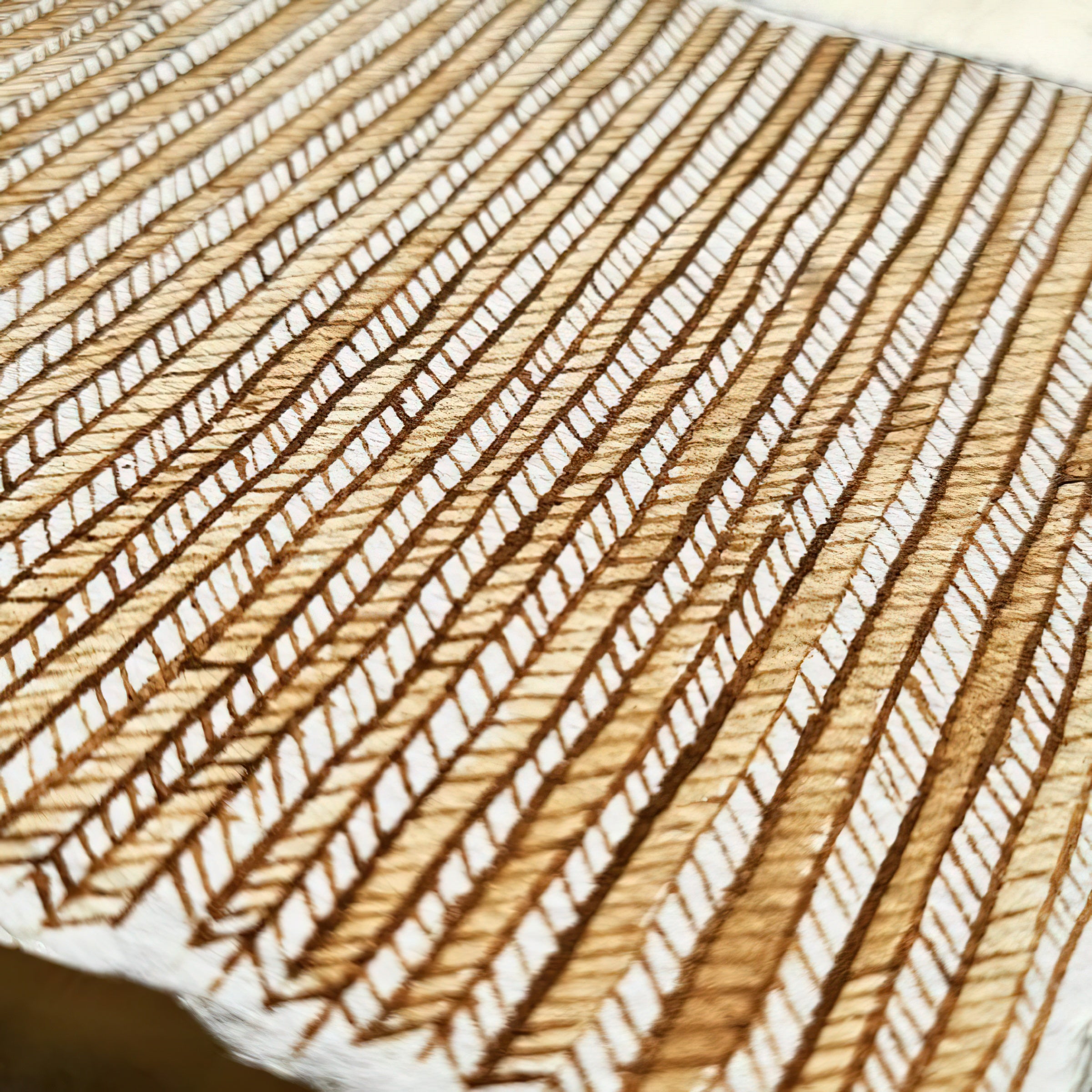

Whakapapa Tuhoe pigment on cotton. Photo by Sarah Hudson.

I am in an art collective called Mata Aho Collective. We’re a collective of four Māori women and we make large scale installations with industrial materials based on Māori textile practices. That’s one part of my collective art making. Another part is Kauae Raro Research Collective, which is myself and Lanae Cable. We are from Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Pūkeko, and Ngāi Tūhoe, and we explore this place where we grew up and see what art materials we can make. We’re interested in the processes of our ancestors, who were self-sustainable and responsive to the environment. I’m finding more and more relevancy through gathering materials in a respectful, reciprocal way. We research, which means walking around and touching mud, talking to people, and digging through historical texts, usually ethnographic descriptions of our people. And we make paint and do paintings.

Lorraine Brigdale (Yorta Yorta):

Lorraine Brigdale (Yorta Yorta):

I am from Victoria, Australia. My clan originates from Maloga on the Murray River. Our family was put on the Cummeragunja Mission in New South Wales. I’ve been an artist since I was a small child. I was an international product designer and coming towards the end of my professional life when my sister and I started to search for our Indigenous roots and tried to make contact with family. As my connection with my family grew, my interest in ochre-based paints grew.

The first step in making paint with natural pigments is foraging. Foraging for food, medicine, and construction materials has been guided by similar cultural protocols in many Indigenous communities around the world. As Hudson explains, “we follow customary practices of only taking what we need and tending to and caring for the environment while we’re there.” Brigdale follows a similar ethos while foraging in Australia; she always asks her Yorta Yorta ancestors for permission to take something and practices reciprocity as a way to give back. “One of the things that I often do when I’m foraging is I take a plastic bag so I can put the rubbish in when I can pick it up,” she says. Logue also believes that natural pigments, along with all natural resource extraction, should be used in accordance with the return of land and asking for permission from the Indigenous caretakers.

Knowing what materials to forage and understanding how to process them can be challenging. Hudson’s research collective uses a combination of ethnographic documents and intuitive foraging to relearn the ochres and processes that her ancestors have used. Logue’s interest in natural pigments began when he stumbled across vivianite, a blue pigment used by Indigenous artists across the Pacific Northwest, in a shell midden while foraging for mushrooms. He has since learned from his Tribe’s basket weavers about the yellow dye that can be obtained from wolf moss and Oregon grape root and transferred this into his painting practice. This combination of learning from tradition, as well as intuitive learning from the landscape, places Indigenous artists at the forefront of development of natural pigment technologies.

Developing an artistic practice based upon natural pigments is not a simple task. Indigenous artists can be shamed for not creating what others perceive as “traditional” art. Additionally, the use of natural resources raises ethical questions. “Leave no trace” principles, contested land ownership, and fears of intensive extraction have all discouraged artists from foraging for their colors. Instead of using the raw pigment, Brigdale processes her ochres to make high quality watercolors. The kinds of paintings she creates are not generally recognized as an Aboriginal use of ochres, and because of this, she is not always recognized as an Indigenous artist in the commercial art world.

Shades of ochre and charcoal. Image courtesy of Lorraine Brigdale.

Brigdale, Hudson, and Logue all spoke of the difficulty of being paid properly as Indigenous artists who create their own materials, especially Hudson, who works in a collective. When the collective runs workshops, gives presentations, or participates in shows, the collective is compensated for the rate of one person’s pay, despite the contribution of multiple people’s knowledge, time, and resources. The collective art making process is a way for Hudson to embed Indigenous community relations into her art, but it makes it difficult for her to make a sustain-able living. The commercialization of natural pigments also raises questions around who is entitled to profit from these materials. Hudson reflects, “When I started using earth pigments, I found it really hard to sell the work. It’s stolen Maori land in the first place, and then there’s a bunch of other stuff going on top of that. I’ve come back and taken a piece, and then I commercially benefit from selling that land again . . . where do I sit in that cycle?”

Brigdale believes that one of the strongest modes of decolonization is education. In talking to people at her shows, she has found that her art provides an opening for people who are curious and allows her to share stories of her Indigenous experience and Aboriginal history. Both Brigdale and Hudson are currently working in schools, encouraging children to play and make art in the natural world while becoming informed on the Indigenous history of the landscape. In this way, the increasing popularity of natural pigments is facilitating the next generation of Indigenous and settler children to build a reciprocal, decolonized relationship with the land through visual expression. Logue also values the perspectives on Indigenous youth, who he says are able to see through so much of the colonial conditioning, and because of that, he “can’t wait for the creations, new perspectives, and the change they are bringing.” Hudson sees the positive ripple effect of this work: “The kids are going to learn how to make paint and go out in the field and that’s so exciting to me. I wish I knew this stuff as a kid, and I’m really excited that these kids will know. My kid knows so much, and she tells all the [other] kids. I’m really proud and excited about that.”

Top photo: Camas Logue in the studio doing an underpainting of oil paint on wood panels. Courtesy of Camas Logue.