Chef Sean Sherman (Oglala Lakota) is working to draw attention to the cuisine of America’s Indigenous cultures and reclaim Indigenous food knowledge. After mastering European dishes in restaurants across Minneapolis, Sherman shifted his focus to the recipes of his ancestors and embraced the budding Indigenous food movement. In 2014 Sherman founded a catering company, Sioux Chef, specializing in Indigenous foods that eliminate the use of European ingredients. Sioux Chef is now an Indigenous-led team with a mission of revitalizing Native American cuisine. He published a popular cookbook, The Sioux Chef, which was recently named “Best American Cookbook” by the James Beard Foundation. In 2015 he launched Tatankatruck, a food truck that features Oglala Lakota specialties such as cedar and maple tea, bison, and wild rice bowls. When Sherman and his business partner, Dana Thompson, decided to open a restaurant, their record-breaking Kickstarter campaign raised nearly $150,000 from 2,358 people in 30 days—more individual contributors than any other restaurant to ever raise funds using Kickstarter. The Sioux Chef team has grown rapidly from just Sherman to 12 employees working round the clock to maintain the catering business while developing the physical restaurant. Sherman’s long term vision is to work with Tribal communities to decolonize diets and bring access to Indigenous foods across the whole United States. Cultural Survival’s Salma Al-Sulaiman recently spoke with Sherman.

Cultural Survival: Tell us about your journey into the culinary world.

Sean Sherman: I was born in Pine Ridge in the early ‘70s and was there until I was about 13. We lived way out in the country, but I had a lot of my family still living at the reservation so we visited often. My parents split up, and my mom moved off the reservation and went back to school. I started cooking out of necessity, just because we did not have a lot of money. I was able to find a job and started working at restaurants as soon as I turned 13. I didn’t really know that I was going to be a chef growing up. I just kept working at restaurants throughout high school, college, and after college. I went to the same university as my mom, Black Hills State University. When I moved to Minneapolis, I kept working at restaurants and became pretty good at it. I got my first executive chef job just after a few years of being in the city. I did not go to culinary school.

I started working with the farm-to-table movement when it was barely a movement. It was nice to work directly with farmers and ranchers around me to really help me think outside of the box. It helped me explore more and more food flavors until I had my epiphany a few years later, realizing that there was no Indigenous representation in the culinary world. It was eye-opening to have that realization that I could name 100 European recipes from English, French, Spanish, and Italian, but could barely think of 10 Dakota recipes. That made me spend a few years researching, experimenting, and reconnecting with plants until I started feeling comfortable to do dinners focused on regional and Indigenous foods, in about 2012.

CS: What makes food a good avenue to reclaim Indigenous cultures?

SS: Food is a really nice center point for people, for understanding and for identity. Food really defines who we are on so many levels, nutritiously, regionally, spiritually, culturally. The removal of food systems [from Native communities] was our driving force; we are centering our whole nonprofit based on returning education and creating food access, which is something that was taken from us, like our ancestors going to boarding schools and residential schools and losing so much culture. [With] the destruction of our natural resources and disruption of land and animal and plant resources, we are lucky to have Indigenous agriculture still alive throughout the U.S. at all. A lot of us as Indigenous communities are basically genocidal survivors. It is important to talk about the history.

CS: How can Indigenous foods and wildlife help the food system?

SS: Indigenous communities all over the world have a blueprint of how to live sustainably using just plants and animals right around you, no petroleum or anything. Much of Indigenous education centers around food: how to hunt, fish, farm, gather and process food, how to use tools and weapons and all of that. Indigenous education never had a price tag on it, so it seems ridiculous that we are kept in such a state of oppression because of lack of education. Food is the most important part of understanding Indigenous food systems because it is complicated; it is not just like going to a cooking school and learning about French techniques. There is so much diversity within Indigenous food systems all around the world that you could find commonality in technique like food preservation and cooking techniques; you know how people were grinding and drying things. We are looking at the knowledge of the wild foods and plants and understanding they are used not just for food, but also for medicine and crafting. We are also looking at agriculture and the history of agriculture, at the migration of people, and understanding the history in general of how we all ended up where we are. It’s important to utilize this Indigenous education and thousands of generations of knowledge of how to live sustainably with the plants and animals around you. That resourcefulness showcases the need for protecting natural resources and continuing this education, writing it down, and showing the value of Indigenous education over Western education.

CS: Tell us about NATIFS and Indigenous Food Labs.

SS: As we were getting ready to open restaurants, we also had this drive that we wanted to do this everywhere. We did not want to have franchise restaurants because we are trying to return a lot of this education to the communities and make Indigenous foods a part of a daily life. We created the non-profit, North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems, utilizing the brand Indigenous Food Labs, which we are hoping to open by the Spring in Minneapolis. Indigenous Food Labs is a nonprofit restaurant that is focused on training people to work with Indigenous foods in a restaurant scene. All of our staff become trainers, so people learn restaurant systems, management, cooking, operations, catering, and all aspects of a full scale restaurant. We also have in the plans a culinary kitchen education center and classroom so we can teach people this curriculum that we want to design around Indigenous food, farming, agriculture, seed saving, foraging techniques, food preservation, salt and sugar fat production... cooking techniques in general. Our goal for Indigenous Food Labs is to have a large education training center open as a public restaurant and help open other smaller food entities. Basically, we want to be a support and training center. We will help develop everything, including writing the business model and the recipes, and help them build healthy Indigenous food entities for their community that can spur jobs and help bring foods that are culturally relevant to their particular place, land, history, and people. Our goal is to open Indigenous Food Labs everywhere we can throughout North America, largely in the United States but also eventually in Canada and Mexico. Hopefully this will be a resource for anybody around the world to utilize similar techniques to help develop and revitalize Indigenous food systems anywhere, using restaurants as a center point that people not only go to, but learn from.

CS: How can people access Indigenous ingredients?

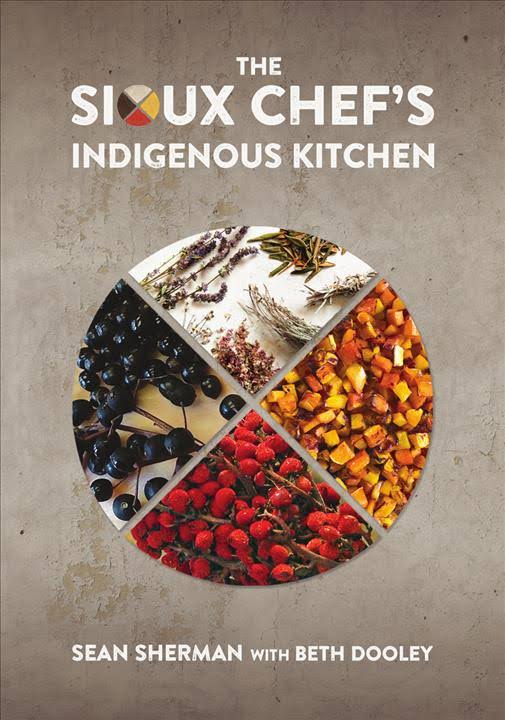

SS: We wanted a cookbook to give people my idea of how we approached food and how they can similarly approach food, no matter what region they are in; not to use the exact same ingredients that we have in our region, but to look around and see what is out their back door. Utilizing that concept and thinking about wildfoods, agriculture and history, the processing and the cooking technique and why it is important to decolonize foods; to know why we have pushed so hard to remove the dairy, the wheat flour, the processed sugar, and even beef, pork, and chicken, just to prove a point that there are other protein sources out there. We see that we can start to spur Indigenous regional food hubs all over the place, because no matter where you are in North America there is beautiful Indigenous history and all sorts of different foods. We have been able to go coast to coast and play with whatever food and history and different flavors that are in those regions, opening the doors for so much more plant diversity in people’s diets. There are so many plants that are not being utilized at all, that are completely perfect food sources, and we literally step on them all the time.

CS: What are your plans for the future?

SS: We are hoping we can start working on opening our first Indigenous Food Labs in different parts of the country, like Albuquerque, Denver, Seattle, Boston, or Chicago, to help those respective regions to do that same work to help the Tribes around them to solidify and revitalize the food systems and to grow those economic opportunities. We are also going to be working on the next book iteration, taking a deeper look at North America as a whole.

Sioux Chef's Recipes:

Squash and Apple Soup with Fresh Cranberry Sauce

Wagmú na Tȟaspáŋ Waháŋpi nakúŋ Watȟókeča T’áǧa Yužápi

Serves 4 to 6

This rich, flavorful soup has a creamy texture without cream. We use the small, tart crab apples that grow in backyards and along the borders of farm fields.

2 tablespoons sunflower oil

1 wild onion, chopped, or ¼ cup chopped shallot

2 pounds winter squash, seeded, peeled, and cut into 1-inch cubes

1 tart apple, cored and chopped

1 cup cider

3 cups Corn Stock, page 170, or vegetable stock

1 tablespoon maple syrup or more to taste

Salt to taste

Sumac to taste

Cranberry Sauce, or chopped fresh cranberries for garnish

Heat the oil in a deep, heavy saucepan over medium heat and sauté the onion, squash, and apple until the onion is translucent, about 5 minutes. Stir in the cider and stock, increase the heat, and bring to a boil. Reduce the heat and simmer until the squash is very tender, about 20 minutes. With an immersion blender or working in batches with a blender, puree the soup and return to the pot to warm. Season to taste with maple syrup, salt, and sumac. Serve with a dollop of Cranberry Sauce.

Cranberry Sauce

Watȟókeča T’áǧa Yužápi

Makes 1½ cups

Use this to drizzle over roasted squash or turkey, on Wild Rice Cakes, page 63, or for a dessert sauce.

1½ cups cranberries, fresh or frozen

¼ cup cider

¼ cup maple syrup

Salt to taste

Crushed juniper to taste

Put all the ingredients into a saucepan and set over medium heat. Bring to a simmer, stirring occasionally, and cook until the cranberries have popped and the mixture is thick. Remove from the heat and put into a fine-mesh sieve set over a bowl. Press the mixture firmly with the back of a spoon and scrape the underside of the sieve to capture all of the fruit pulp. Taste and adjust the seasoning. Serve warm or cool.

.