I remember reading somewhere that culture is constantly under construction. This passage began by recalling an anthropological conference where one eager student’s question became a key to understanding humanity: “Anthropologist Margaret Mead, what do you consider to be the oldest sign of civilization in a culture?” All of the attendees, rooted in their disciplinary structures, expected the answer to be about material vestiges such as spears, clay pots, or grinding stones. But to the contrary, Mead replied that the first sign of civilization in an ancient culture was a femur that had been broken and then healed.

Mead explained that in the animal kingdom, if you break a leg, you die, because you can’t run from danger, go to the river to drink, or look for food. You are easy prey for predators and plunderers. No animal survives long enough for a broken leg bone to heal. A broken and healed femur is evidence that someone took the time to care for their fellow animal, dress the wound, carry them to safety, and help them recover. Mead said that helping someone in need is where the civilization of our species begins; it is where humanity begins.

To understand the Andean restoration process through the situation of Indigenous Peoples in the Peruvian Andes, it is essential to contextualize the recent events that have caused the current political crisis in the country. The social upheaval in Peru began with a political siege by the Fujimori opposition (1990–2000) and other political parties, which never accepted the democratic election process and created obstacles for then-elected Indigenous President Pedro Castillo to govern. Violence worsened with the political suicide of Castillo, who, on December 7, 2022, dissolved the Congress of the Republic and consequently paved the way for the succession of Dina Boluarte as the new President of the Republic of Peru.

“The Taking of Lima” massive mobilization by Indigenous Peoples from the interior of Peru marching towards the capital.

Given these events, widespread indignation began from southern Peru. The persecution and harassment of the former president was not limited to the contempt of a political figure of a State, but encompassed the direct disgust, racism, and classism of an alienated class of Mistis (white colonizers) toward a population that in historical times was 80 percent Indigenous, but today is just under 26 percent Indigenous. Almost immediately, campesinos with huaracas (handmade weapons) took to the streets against the National Police and Army. The social costs were high, with more than 60 deaths in less than a month of governance. The social upheaval persisted in southern Peru as Indigenous groups, campesino communities, and grassroots movements remained strong for more than two months until the State suppressed commerce impacting Indigenous groups, who were now seen as terrorists against the State and opposed to national development.

Since then, there have been marches to the capital called “the Taking of Lima,” which have involved the mobilization of groups from the interior of the country to the capital as a way of counteracting the invisibility of the protests in mainstream national media. Now, as a third wave of national mobilization is underway, the wear on Indigenous Peoples is visible, but the results are blossoming.

Today there are more national movements marching together for a national agenda that demands the resignation of the current president, new presidential elections, and justice for unpunished deaths caused by the State. Today, Peru is a panorama of popular consciousness that has awakened and intends to fight against the groups in power, which would not have been possible had the people not maintained the resistance.

Mothers saying farewell to their children on their way to the “Taking of Lima.”

Things are not and cannot always be the same; everything flows, changes, and transforms, as my Andean brothers say. Life follows a dialectic of contradiction rather than opposition. It is not that the day is opposed to the night or that the male is opposed to the female, but that they are complementary. Opposition denies the existence of the other, while contradiction allows the amalgamation and coexistence of both for something better. Andean cosmovision holds a philosophy based on the whole being and happening, which is best explained in its principles of reciprocity and complementarity that materializes the sumaq kawsay (living well), or qhapak ñam (right way of life). These principles govern ethical life in community and make collective life possible. There may be, as in any reality, something that unbalances this archetype, but there will also be an antidote that neutralizes and produces an immediate cultural response to cure it.

In the Andean world there is a device of epistemic self-correction to heal or reestablish the existing order called Chaninchay. Chaninchay is the perception of justice and balance for all things, where reality is a subjective community construction not linked to the individual, nor to the theocratic divine of morality, but rather, as a universal but relational animated whole where everything has or possesses soul and feelings. This relationship is constantly nurtured by fellowship, solidarity, and reciprocity in order to seek a diverse, balanced, and just community whole.

So, how does the Andean society heal and restore its balance after the recent political crisis in Peru? How do they rebuild their individual and collective existence after events such as those experienced on January 9, when 17 protesters were killed and 68 injured in a deadly clash with police in Juliaca? For the Andean society, these events are not random or casual phenomena. They understand that the origin lies in the historical process, which, obeying its law of cycles, arises and sprouts every so often. Time is for them an update of the past, but with particularities of the present that make the future possible. The Andean world knows that what is uncertain in Western philosophy—the future—is, in reality, what is known and lived in the qhipnayra (past); the future is the lived past in the Andean world. From this perspective, the Quechua and Aymara communities are activating diverse mechanisms invisible to the eyes of the socially alienated. The myth of the inkarri, that “some will die but we will return as millions,’’ is an element of ethnohistoric memory that is activated in each process of resistance and restoration of harmony.

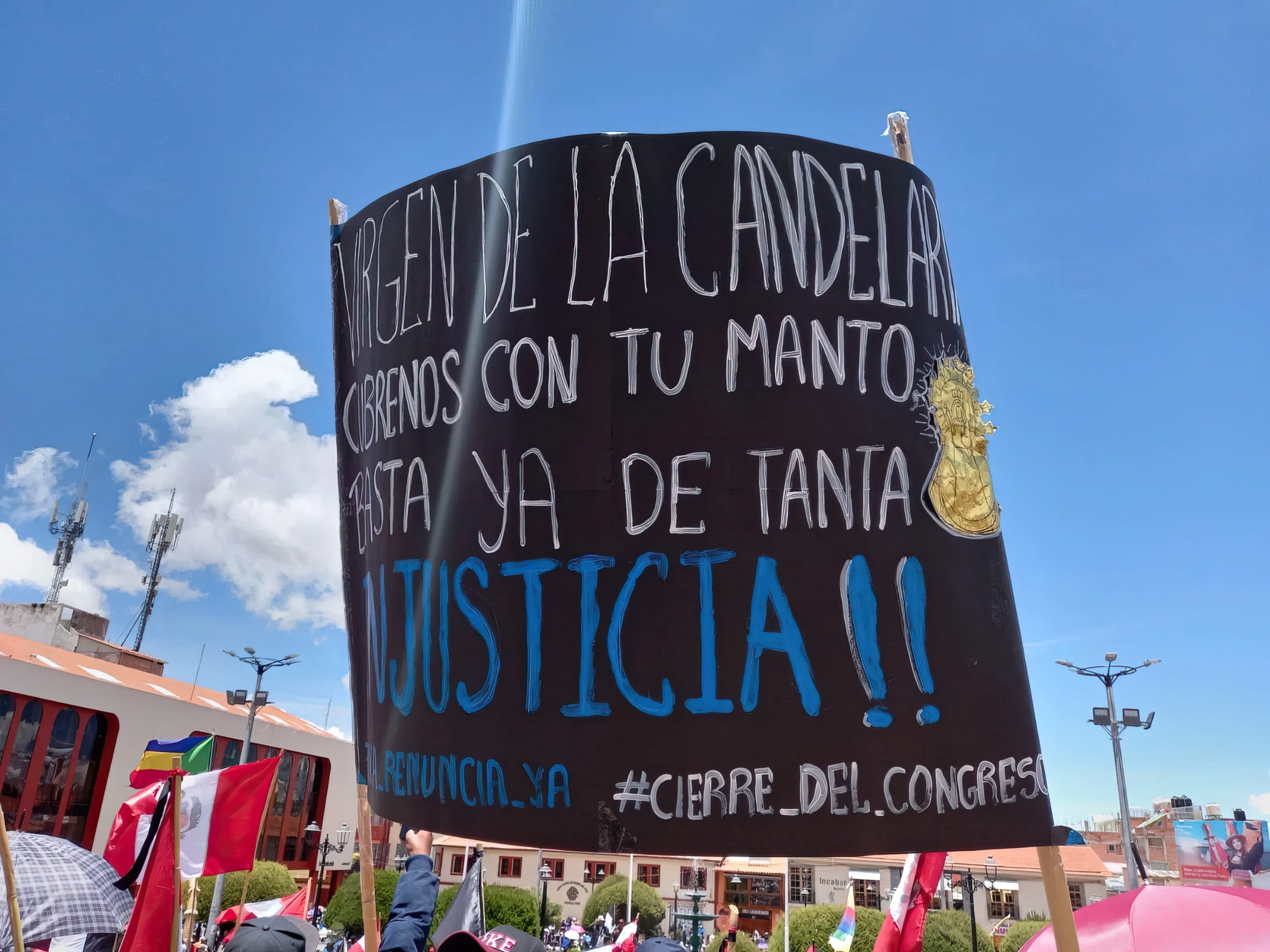

Request to the Holy Virgin Maria de la Candelaria (embodiment of Pachamama) of Puno for protection and to stop the violence against the Indigenous defenders.

The restoration of the Quechua and Aymara communities of Peru has begun with their rituals around cycles of Pachamama and Pachakamaq, the Earth and the sun. Festivals and ceremonies play an important role in this healing process. In the Andean world, individuals cannot be healed if their social environment is not healed first. That is why there is no better moment than at group meetings. Celebrations cease to be a simple presence of music, food, and dance, as they are often interpreted by outsiders, and become a process that collectivizes and shares pain. After the State violence, people accompany the bodies of those lost with chants and funeral dances that free the relatives from individual suffering and help keep the memory of the fallen people alive.

Today, the State’s process of making amends for its crimes and injustices with monetary payments and psychotherapy for relatives of the victims is being questioned, as if the violence perpetrated could be solved with materialism. The State has even tried to buy the communities’ forgiveness through regional economic bonds, but they have not succeeded. The social and historical fissure has already been made, and the resistance will perpetuate. The Andean world is being continually restructured. The people who were there before cannot be separated from the people who intend to stay today. Jallam wayqipanaykuna! Nuqanchik kachkaykuraqmi! Long live our brothers and sisters! We will continue and will continue to exist!

Top photo: Women marching to bring attention to the murders carried out by the State against their young children

All photos by Ronald Callocondo