Imagine for a moment that you are standing outside in the blue-grey dawn of the Australian Great Sandy Desert. The temperature hangs in the low 60s and the surrounding light is inky and hard to see through. Above you, the sky is still littered with stars as far as the eye can see. As you stare up at them, you begin to lose track of where the earth ends and the sky begins. This is what it feels like to walk into Stephen Gilchrist’s “Everywhen” exhibition, currently on display at Harvard Art Museums through September 18, 2016. Gilchrist, who is of the Yamatji people of the Inggarda language group, has been working on this collection in collaboration with Harvard Art Museums for the past five years. A man of patient and thoughtful demeanor, he designed the exhibition to engage the complex relationships between Australian indigeneity, identity, and time. “The exhibition is thinking about time and power and who gets to claim it,” Gilchrist explains. “We’re thinking about art history, the category of the ‘primitive,’ and the social category as well. Many people think that Aboriginal people are assigned to the past. So, I wanted in my curatorial approach to think differently—to think about curatorial practice not as preservation, but as activation.” The curator’s desire to activate the space is felt both in the physical design and in the careful selection of the 70-plus works on display. The gallery is broken up into four sections: Seasonality, Transformation, Performance, and Remembrance. Despite these distinct thematic regions, “Everywhen” is designed in a looping figure eight pattern, so the audience always returns to the beginning of their journey at the end. “It’s a conceptual approach to thinking about how time is divided,” says Gilchrist. “The idea of the exhibition is this occupation of space but also the occupation of time. So when you’re moving through the gallery, you’re also moving through these various time zones.“ Seasonality, the first room that visitors enter, is focused on natural time and highlights how ecological ideas are mobilized alongside ideas of belonging. One of the first works that the audience comes across is Gulumbu Yunupingu’s “Garak IV” (The Universe), an incredible series of thousands of stars painted in earth pigments on eucalyptus bark. Gilchrist considers this one of the key works of “Everywhen,” as it challenges the audience to bend their understandings of modernity and Indigenous presence:

This work is all about collapsing temporalities. It’s a depiction of the night sky, but you’re looking at these stars that may have already burnt out. It’s this idea of light that is already dimmed across these unfathomable distances into our present, so it’s a metaphor for how the past is presenced in our present. I was thinking about how Aboriginals don’t physically live in the past, but the past is still revered and held sacred. These narratives of the dreaming that disclose how the world came into being are not just about narratives of the past, because they also tell us how to live in the present, which sustains generations to come. So it’s more complicated than people think. We [Aboriginal people] think of these as breathing objects, and in them we embed and condense all this cultural information.

The room that follows, Transformation, illustrates the historical struggle of Aboriginal artists to gain recognition on a global scale. In part, Gilchrist attributes the increase in global acceptance of Aboriginal art to the seminal works of Albert Namatjira. From the 1930s to the 1950s, Namatjira produced hundreds of works using primarily modern styles and techniques. He was recognized by the Australian public as a great national painter, and was the first Aboriginal person to be granted Australian citizenship. Gilchrist is clear to add, however, that it wasn’t until the 1970s, when Aboriginal artists were painting more distinctly in their own iconography, that the larger battle for recognition was fought. In modern-day Australia, roughly 50 percent of all professional artists identify as Indigenous, and there is a strong national acceptance and familiarity with Aboriginal art styles. But that level of acceptance has yet to take hold internationally. Gilchrist notes that one of the show’s aims is to make people more aware of Aboriginal art traditions and the 400 million Indigenous peoples around the world. As he explains, “There is an important cultural imperative to painting. The community can feel that they are co-owners of this work; the artists are making decisions and negotiating. To me, it’s about privileging artists’ voices, privileging Indigenous voices. The provocation of the show is to imagine the world otherwise. . . colonization is not the meta-narrative of indigeneity. It’s about seeing the ways in which Indigenous artists are taking this type of painting, creating something new, and reconstituting it.”

Following the Transformation room, the exhibition weaves visitors through the Performance area, which focuses on rhythm and gesture in Australian Indigenous works, and concludes in the resounding Remembrance space. The Remembrance space engages Indigenous art on multiple levels, incorporating monochromatic painting, photography, writing, and sculpture. In explaining why he decided to strip away bright colors from the Remembrance section, Gilchrist says, “The past unfortunately erupts into the present for so many Indigenous Peoples around the world. Aboriginal people have been at the place now termed ‘Australia’ for at least 40,000 years, so the knowledge of those 400 generations, and what has been lost in the [preceding] 228 years, is resounding. I thought it was really important that we linger in these spaces of discomfort and talk about the history of what happened. But it’s also not to try and present Aboriginal people as always being victims, and not always this deficit of loss. There is power in renaming it.”

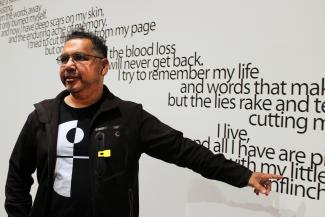

Of particular impact in this final section is a wall-sized print of vinyl text entitled “many lies” by Vernon Ah Kee. The text runs diagonally along the wall in the shape of a scar, and concludes with the resounding words: “I try to remember my life / and words that make me strong / but the lies rake and tear at my roots, / cutting me from the earth. / I live, / and all I have are pieces of truth. / but with my little pieces / I am unflinching and unforgiving.” It is in this room that the magnitude of Gilchrist’s thoughtful work collides with the many complicated histories of Indigenous Australians. By creating a space of tension, the curator has wisely opened up the opportunity for an honest dialogue. “I think it’s difficult to get people to see things through Indigenous eyes, [an] Indigenous lens,” Gilchrist says. “But time is something that people experience every day, so you’re just asking them to recalibrate. Like when we look at “Garak IV” in the beginning. We see that the sky is innocent of these colonial narratives. The land, unfortunately, is not. But this exhibition is thinking about what that in between space would look like.”

Photo: Artist Vernon Ah Kee (Yidindji, Kuku Yalandji, Waanji, Koko Berrin and Gugu Yimithirr peoples) standing before his many lies installation.

All photos courtesy of Harvard Art Museums.