By Nina Sangma (GARO)

Where are we, the world’s Indigenous Peoples, going to be in the age of Artificial Intelligence? What will be our situation as Artificial Intelligence becomes an everyday reality for those of us, the “othered,” who have been left out of rooms and histories and memories? Historically oppressed and politically disenfranchised, Indigenous Peoples have served as test subjects for centuries of systemic silencing and dehumanization.

The human condition today is centered on and propelled by data in an endless continuum of consuming it, harvesting it, living it, and generating it through loop after loop of digital footprints on platforms meant to compete with sleep. For Indigenous Peoples, our identities are predestined and politicized, defined by our resistance as our existence through the ages and stages of colonization and imperialism to the present, the “age of AI,” which will exacerbate existing inequalities and violence.

Many of us have begun to unravel the extent to which AI will determine the human condition and have arrived at the inconvenient truth that AI is a bridge to unspeakable horrors if its governance does not prioritize the lived realities of those on the margins. Development per se has always been a dirty phrase to us, the Indigenous, who have borne the burdens of colonizer States’ so-called “developments” on our ancestral lands. Given their records, we can hardly expect States and corporations to regulate AI through governance that is aimed at being truly ethical and centered on the guiding principles of business and human rights.

Left and center: Nina Sangma (far left) at the Internet Governance Forum 2024 in Kyoto, Japan.

The stark truth is that the core values that protect human rights are counterintuitive to the values of corporations for whom it is “business as usual.” If democracy were profitable, human rights lawyers and defenders wouldn’t be sitting around multi-stakeholder engagement tables demanding accountability from Big Tech and creators of AI. The cognitive dissonance is tangible in spaces where the presence of a few of us who come from the Global South and represent Indigenous perspectives often leave these spaces feeling like we’ve been patted on the head, roundly patronized by the captains of industry.

A statement released last year on the existential threats posed by AI that was signed by hundreds of AI experts, policy advisers, climate activists, and scholars underlines their well founded fears that we are hurtling towards a future that may no longer need humans and humanity, and that collective interventions and accountability frameworks are needed from diverse groups from civil society to ensure strong government regulation and a global regulatory framework.

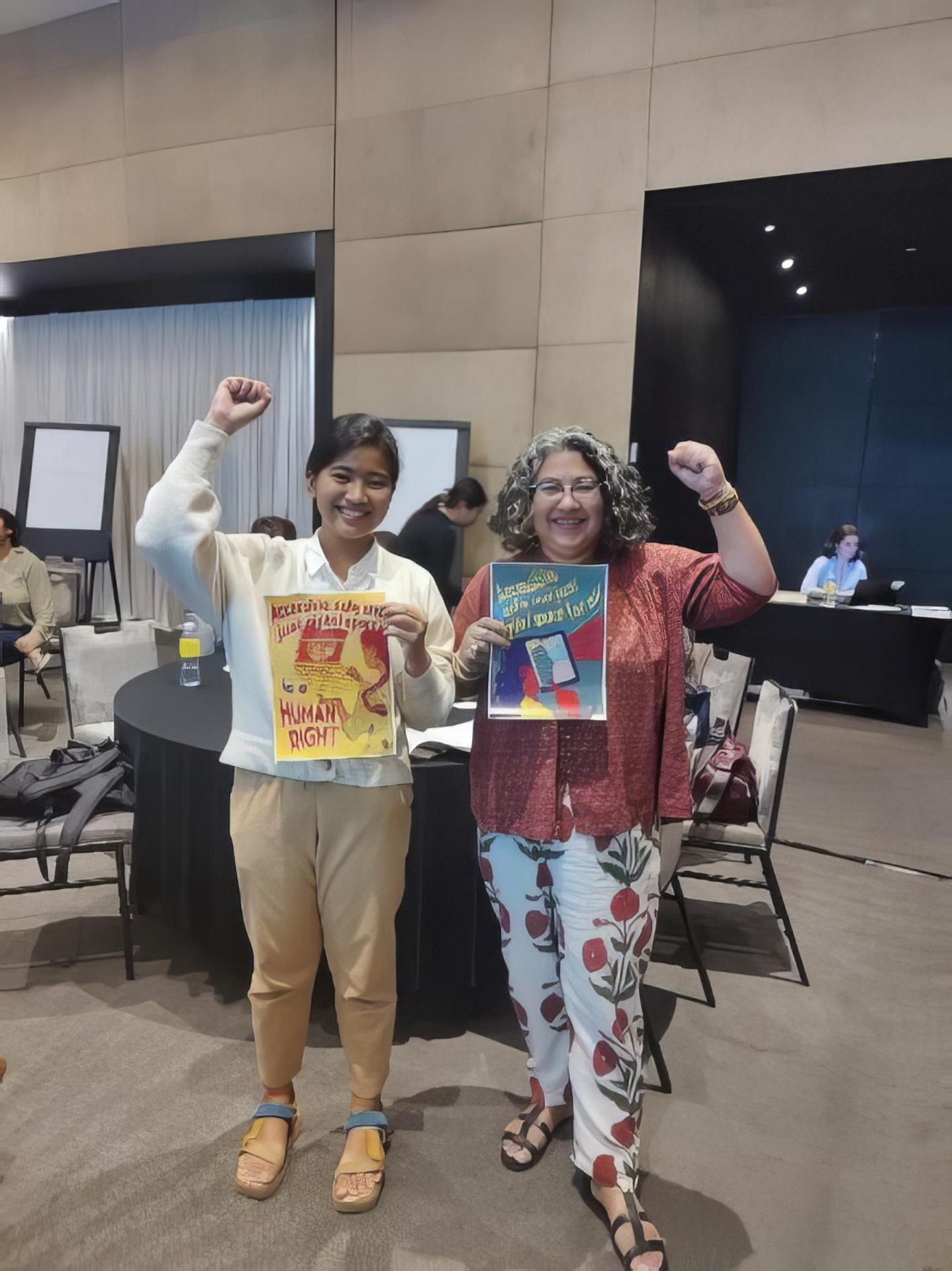

Eloisa Mesina, SecretaryGeneral of Katribu Youth, and Nina Sangma at the Asia-Pacific Conference on Internet Freedom in Bangkok, Thailand. All photos by Nina Sangma.

AI cannot, and should not, be viewed in isolation. Preceding technologies have been the bridge to AI and will continue the prejudices and biases embedded in existing technology. One of the biggest concerns is the use of surveillance tech like Pegasus, which is being used to subvert democratic rights of citizens and free speech, including the targeting of journalists to curb freedom of the Press and citizens’ right to information under the guise of national security. This, coupled with draconian laws like India’s Armed Forces Special Powers Act, gives unbridled powers to the Army in so-called “disturbed areas” to maintain the status quo. These areas coincide with Indigenous lands where there is an Indigenous population, such as in Northeast India.

Independent Indigenous journalist and Fulbright scholar Makepeace Sitlhou reporting from the buffer zone in Manipur, India. Photo courtesy of Makepeace Sitlhou.

Historically, the heavy-handedness of the State has served as a fertile learning ground for testing adoption strategies to exercise control over other areas in India, always with the sinister goal that coincides with and aims at the dispossession of Indigenous Peoples from resource-rich lands to create value for a few corporations and their beneficiaries. The use and justification of surveillance tech are pinned on creating the need for protection from “antinationals” or “terrorists,” terms commonly used to label and libel anyone critical of the government. Both the Duterte and Marcos Jr. governments have continued to put Indigenous activists at risk through the practice of “red tagging” to suggest links to communists in the Philippines.

Online violence often precedes offline tactics, which led to deadly attacks on nine Indigenous leaders who were gunned down in December 2020 for protesting against the Philippines government’s dam projects. Almost a decade ago, in a similarly chilling encounter in June 2012, 17 Adivasis falsely accused of being “Maoists” were killed in extrajudicial killings in the state of Chattisgarh, India, a mineral-rich zone that has attracted mining companies and led to the forced eviction of thousands of Adivasis. Most recently, the use of facial recognition and drone technology is being adopted in the northeastern Indian state of Manipur to quell the ongoing civil unrest in the state.

Nina Sangma (far left) with Pyrou Chung, Director of Open Development Initiative, East West Management Institute and independent Adivasi journalist and poet Jacinta Kerketta at RightsCon 2023 in Costa Rica.

The question of whom and how the government identifies as a person of interest will depend on who technologies mark as suspicious. What existing databases will it tap into, and how are these databases equipped to correctly profile citizens, given the inherent flaws in pattern recognition and algorithmic biases in its training sets? Are there not some identities more likely to be marked suspicious based on their political histories, religions, and records of resistance to State oppression? And in whose favor will these technologies be deployed to justify occupation and win wars and elections? In digitized political economies, the incentives to use technology for good to prioritize the welfare of citizens are low when compared to wealth creation for a few that rely on maintaining the status quo through ongoing systems of oppression.

The role of disinformation campaigns in winning elections is an outcome all governments are aware of on both the ruling and opposition sides. We are in a war of narratives where the battleground is online, on social media and messaging apps, in the daily propaganda of corporate media and the hate speech targeting minorities, scholars, and critics, and the subversion of history with nationalistic texts and takeover of public institutions. AI will certainly prove to be a cost-effective way to spread hate speech and disinformation in terms of not just efficacy, but relying on existing quantities of hate speech and distortion of facts to churn out vast amounts of unverified information.

What that means is that we, the users, are forever doomed to be stuck in a content verification and content recommendation loop based on what we consume online, leading to more polarization than ever before. An especially gruesome thought is the industrial levels of technology-facilitated, gender-based violence that will be unleashed. Think revenge porn using AI-generated deep fakes, the building blocks of which lie in existing disinformation campaigns targeted against women to undermine their professional credibility and reputations. Online hate towards women is almost always of a sexually violent nature. Simply expressing an opinion as a woman is enough to warrant harassment and a slew of vile abuses from rape threats to calls for murder and deep fakes, the articulation of which will be gut-wrenchingly innovative with generative AI tools like ChatGPT and Dall E.

In the UNESCO report “The Chilling: Global Trends in Online Violence against Women Journalists,” a staggering 86 percent of Indigenous women journalists reported experiencing online violence. The storm of technology-facilitated, gender-based violence spikes during conflict and for women journalists reporting from conflict areas.

A gruesome mirror of ground realities where women’s bodies become a battleground and rape is a political tool is being witnessed in the ongoing ethnic violence in Manipur. The trend of heightened attacks by trolls is something Indigenous journalist Makepeace Sitlhou (Kuki) has experienced firsthand on Twitter as a result of her award-winning ground reportage from volatile regions. Unfazed by these online attacks, things took a troubling turn when Sitlhou was named in a First Information Report for allegedly “. . . misleading statements and to destabilize a democratically elected government, disturb communal harmony by creating enmity amongst communities, and to defame the state government and one particular community.”

When asked if the probability of online attacks paving the way for offline violence was high and whether deep fakes could be used as an online tactic, Sithlou agreed, saying, “The concerted trolling led up to an actual police case filed against me over my tweets.” When asked if this could mean that the use of AI-generated deep fakes was a possibility, she responded, “The way it’s happening to other journalists, it’s more likely an inevitability.”

In a remarkable turn of events, the Supreme Court held criminal proceedings against Sithlou after Kapil Sibal, a high-profile advocate, appeared for her. Her situation underlines the need for access to legal help, a privilege not many Indigenous journalists have. Sitlhou commented, “I was lucky to have easy access to good Supreme Court lawyers because I’m well connected to folks in Delhi. But for more grassroots journalists, they must be regularly in contact with their editors and journalists’ unions and keep them posted on the threats that they are receiving.”

Mia Magdalena Fokno at BENECO protest in the Philippines. Photos courtesy of Mia Magdalena Fokno.

Another story of personal triumph over systemic injustice and the importance of pursuing litigation is of Indigenous journalist and fact-checker Mia Magadelna Fokno (Kankanaey), who won a cyber misogyny case against a troll in the Philippines. She underscored the need for building safe spaces online and access to legal aid, saying, “Access to safe spaces and legal services is crucial for Indigenous women, especially female journalists, who face online attacks. The court victory against gender-based online sexual harassment is a significant triumph for women’s rights. This ruling sends a strong message against the use of technology to terrorize and intimidate victims through threats, unwanted sexual comments, and the invasion of privacy. This landmark case . . . underscores the importance of legal recourse in combating online harassment. This victory is a step towards creating safer online and physical environments for all, particularly for Indigenous women and female journalists, who are often targeted. Let this case inspire those who have suffered sexual harassment to seek justice and support each other in fostering safe spaces for everyone.”

Testimonies and firsthand accounts from Indigenous reporters are critical for challenging mainstream discourse and its dehumanizing narrative slants against Indigenous Peoples, which has set the stage for cultural and material genocides—something Indigenous Peoples are all too privy to, having been reduced to tropes to suit insidious propaganda for centuries. Technology in the hands of overly represented communities disseminates these harmful narratives and metaphors at alarming scale and speed, particularly in Indigenous territories, which are often heavily militarized zones.

Mia Magdalena Fokno after filing a case against her troll, Renan Padawi.

“As a fact-checker based in Baguio City, Philippines, I recognize the evolving landscape of journalism in the age of AI,” Fokno said. The emergence of sophisticated AI tools has amplified the spread of disinformation, presenting unique challenges that require specialized skills to address. Journalists, especially those engaged with Indigenous communities and human rights issues, need targeted training to discern and combat AI-generated misinformation effectively. This training is vital to uphold the integrity of information, a cornerstone of our democracy and cultural preservation, particularly in areas like northern Luzon where local narratives and Indigenous voices are pivotal. The need for fact-checkers to adapt and evolve with these technological advancements is more crucial than ever.”

A deeper dive into large language models reveals the fallacy of Big Tech and AI. Large language models (machine learning models that can comprehend and generate human language text) are designed not only to respond to lingua franca, but also the most mainstreamed beliefs, biases, and cultures, leaving out anyone who is not adequately represented in these data sets, and will therefore be representative only of those who have access to social, economic, cultural capital, and digital literacy and presence.

An image I posted on Facebook recently of Taylor Swift standing next to someone wearing a Nazi swastika symbol on his t-shirt was taken down because it went against community standards and resulted in profile restrictions. On requesting a review of the image, Facebook sent me a notification stating that I could appeal its decision to the Oversight Board—a group of experts enlisted to build transparency in how content is moderated. But how feasible is that, given the sheer volume of cases generated daily? And more importantly, which kinds of cases among the thousands, if not millions, that are flagged make it to the final review table? If the bots cannot differentiate the problem at the source level or read the intent behind sharing a problematic image, can it be expected to think critically as so many believe AI will be able to do?

Given this existing lack of nuance, AI will, in a nutshell, perpetuate western or neocolonial standards of beauty and bias with limited localized context. Missing data means missing people. With ChatGPT, for example, there is a real possibility of loss in translation between what is prompted by the user and what is understood by machine learning and the results it generates. Intellectual theft of Indigenous art, motifs, and techniques to the appropriation of Indigenous culture and identity by mainstream communities means that e-commerce websites and high fashion stores will be replete with stolen Indigenous knowledge.

Tufan Chakma with his art and family. Courtesy of Tufan Chakma.

With the advent of Dall E, which can create art from text prompts, Indigenous artists like Tufan Chakma are even more vulnerable to copyright infringement, something he is no stranger to. “I faced it too many times,” he said. “The action I took against it was to write a Facebook post. I also reached out to those who had used my artwork without my permission.” The only protection he gets is in the form of his online followers flagging misuse of his artwork. He added that plagiarism happens with digital artwork because it is a lucrative business to convert into commercial products like t-shirts and other merchandise.

Art by Tufan Chakma. Courtesy of Tufan Chakma.

Apart from the loss in potential revenue, the deeper impact of plagiarism on the artist, according to Chakma, is that “Plagiarism can demotivate anyone who is creating art to engage with society critically.” Chakma’s artwork is political and raises awareness through artistic expression of the plight of Bangladesh’s Indigenous communities. Can AI generate art that speaks truth to power in the manner of an artist who, like Chakma, seeks to change the world for the better? Will AI be able to understand power dynamics and generate art that sees historical injustice and prejudice?

Indigenous identity is encoded in our clothing woven with motifs rife with meaning, intrinsic to our moral codes, core values, and our relationship with nature and the cosmos, a tangible link to our ancestries. Initiatives like the IKDS framework and the Indigenous Navigator recognize the need for Indigenous Peoples to own and manage the data we collect and reinforce us as its rightful owners to govern ourselves, our lands, territories, and resources. Rojieka Mahin, PACOS Trust’s Coordinator for the Local and International Relations Unit, said “Recognizing the impact of [Indigenous Knowledge Data Sovereignty] on all Indigenous Peoples, particularly Indigenous women and youth, is essential. IKDS embodies a commitment to learning, inclusivity, and improved governance of Indigenous knowledge and data sovereignty. This approach will not only keep our community informed but also empower them to share their experiences with others, underlining the importance of establishing community protocols within their villages. Furthermore, it will enhance the community’s appreciation for their Indigenous knowledge, especially when it comes to passing it down to the younger generation.”

Ultimately, Big Tech is colonization in fancy code. Smartphones, smart homes, smart cities—the focus is on efficiency and productivity. But in the rush to do more, we are in danger of losing our humanity. The reality is, that we will soon be outsmarted out of existence by AI if we are not vigilant.

Nina Sangma (Garo) is an Indigenous rights advocate and Communications Program Coordinator at the Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact.