By Nithin Coca

In the middle of the wedding, my friend's grandma, a short, stocky, but strong aboriginal Taiwanese woman in her 80s, went up on stage. She grabbed the microphone and, after a short introduction in Mandarin, the dominant language in Taiwan, began a Christian prayer in the Atayal language.

The fluid, slightly raspy words sounded quite different than the varying toned, short-syllables of Mandarin. I was in Taichung, Taiwan, a groomsman for my good friend. Here, the attendees were mostly Atayal, one of the 16 surviving aboriginal tribes of Taiwan, as the ceremony was for the Indigenous side of my friend's family.

Taiwan is unique linguistically. Dominating are three Chinese dialects; Mandarin, the national language, Taiwanese, the most widely spoken, similar to the Hokkien dialect in mainland China, and Hakka, a distinct dialect from southern China. These three languages, all part of the Sino-Tibetan language group, the second most widely spoken language group in the world after Indo-European, represent more than 95 percent of the island's 23 million people.

Throughout my time in Taiwan I saw this diversity, as I learned how to distinguish between the three languages. I found out that many of the older generation do not speak Mandarin, but, conversely, in Taipei, many youth do not speak Hakka or Taiwanese. These three languages alone provided me with a window into Taiwan's unique cultural landscape.

Now, though, at the wedding, I saw that this was only a small part of the picture. It is incredibly easy to live, work, and travel in Taiwan and not realize that an even greater linguistic diversity lies in the islands beautiful, green hills, and rocky, western coast, where the aboriginal peoples of Taiwan reside, the source of one of humanities most astounding migrations and the birthplace of another language group that's tentacles are spread over a far vaster geographical area than the Sino-Tibetan group.

Besides Atayal, there are Truku, Paiwan, Bunun, and many others. They number 500,000 in Taiwan, only 2 percent of the population, severely displaced by migration from mainland China that began in the 1700's, especially the influx of Mandarin speakers who fled with the Kuomintang (Nationalists) in 1949 and took control of Taiwan.

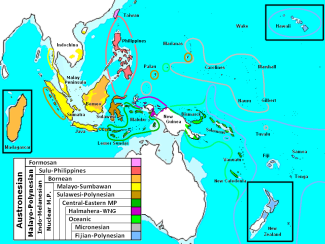

Aboriginal Taiwan's history long predates that of Chinese Taiwan. It is unknown how and when the island was first populated, but archeological records of settlements date back thousands of years. What is known is that, beginning in 300 AD, Austronesians (often referred to as Polynesians) became the first great seafarers in human history. Ships set sail from Taiwan down to the neighboring Philippines, then, in the greatest period of exploration until Columbus' voyage across the Atlantic, Austronesian sailors spread to a huge part of the world, colonizing vast territories.

Tagalog, Indonesian, Malay, Maori, and Hawaiian languages can be traced back to Taiwan, the birthplace of Austronesian people and languages, the world's third most spoken language group. Taiwan's Indigenous people are the ancestors of one of the greatest, most influential stories in human history.

Even more amazing, despite the spread of Austronesian peoples, is that there is more linguistic diversity on Taiwan than the rest of the Austronesian world. That is to say, Truku and Atayal are more different than Malagasy (Madagascar) and Maori (New Zealand) are from each other. In fact, three of the four branches of Austronesian language tree can only be found in Taiwan.

Taiwan's true beauty is this, the astonishing diversity, preserved over thousands of years. One that, today, is facing its greatest challenge in the face of globalization and Mandarin Chinese dominance.

This I could clearly see at the wedding. My friend's grandma was still praying, and I listened attentively, trying to grasp the unique sounds of Atayal, to see if I could hear the distant connection between it and the Austronesian language I am learning, Indonesian. I couldn't. It ended too fast, and the cacophony of Mandarin once again took over.

I looked at my friend, who can understand, but not speak, Atayal. In fact, none of his cousins can speak it. They are passive listeners, the first step towards language loss.

He is going to have kids soon, who will not likely get the chance to learn Atayal. With that, a link that connects them with their past, with those countless generations, with the Austronesian sailors who spread the language and culture of this small island to the far corners of the world, will be broken. The history of Taiwan, one that is extraordinary, but little known and of little use in our modern world, is being lost.

It's already started. Just one hundred years ago, Taiwan had 26 aboriginal languages, but in the past century, 10 have gone extinct, two are moribund, and several others endangered. The day may come when the island only speaks Chinese dialects, and Taiwan's uniqueness is a mere relic of the past.

This is culture loss in action, the causes clear, the consequences quietly, softly, grave.

At the wedding hall, the dominance of Chinese was apparent – the "lucky" characters hanging on the walls, the round tables, and, most of all, the languages spoken around us. The entire ceremony, minus the short prayer, was in Mandarin Chinese, as were all the conversations and songs.

But at the end of the night, after the ceremony was finished, the bride had gone home, and the younger generation – my friend's cousins – had all left, it was only us, the groomsmen, and the elders awake, a strange mix. They looked different than most Taiwanese, with darker skin, larger eyes, and straight, sometimes curly black hair, like their ethnic cousins in the Philippines. Out came a bottle of Johnny Walker, and long lines of shots were thrust into our hands. There was no way we could say no. Smoke filled the air, along with a sense of relief and joy.

Spontaneously, one of the elders began singing. Soon, a chorus began – traditional Atayal songs. I whipped out my camera, wanting to record this amazing moment, but for some reason, the record function simply refused to start. Smiling, I put the camera down. Modern technology and traditions didn't mix at this moment. The irony. We try to capture culture through recording, digitizing, but can this moment truly be captured?

I felt as if I was seeing and hearing something truly special, a glimpse into the heart of humanity and our long existence on this earth. But I couldn't enjoy it fully, because I couldn't help wondering if I was seeing the last gasps of a threatened culture.

A week later, I was traveling around the country and found a host from the Truku tribe, who reside in the less populous eastern coast of Taiwan. It was the perfect opportunity to learn more about indigenous culture in Taiwan.

Dylan was a stocky young man, with darker skin and wider eyes that distinguished him from most Taiwanese. He was proud of his culture, willingly teaching foreign visitors about aboriginal Taiwan, and was fluent in both Mandarin and Truku.

"My mother would not let us speak Mandarin in our home. She would say to speak Truku language," he told me.

Language has to be used to survive, a fact obvious yet too easily forgotten. No amount of funding can replace a dedicated, loving mother. This, I saw, was what was meant by the term "mother tongue". Sadly, Dylan's mother passed away just six months before I met him, a sad loss as she was someone who, Dylan told me, knew the traditions and cultures of the Truku tribe, many of which may be lost with her passing.

Nevertheless, Dylan is growing up in a new age. Taiwan democratized in the 1980's and 90's, and that openness allowed it to finally recognize the rights of its indigenous peoples. Attitudes began to change and new organizations sprung up to do innovative work promoting and preserving Taiwan's cultural legacy. The central Government setup an aboriginal affairs council, and there is now an indigenous people's television network, one of the first in the world, launched in 2004, that broadcasts nationwide on social and cultural issues with the goal of informing both aboriginal and non-aboriginal peoples.

Nonprofits are also growing in scope. The ATAYAL organization, named after my friend's tribe, is taking a unique approach, seeking to reconnect aboriginal Taiwanese with other Austronesians around the world, building bridges between through cultural exchange between disperse islands peoples and their distant ethnic Taiwanese ancestors. This will help aboriginal Taiwanese to realize their unique place in the linguistic world. Other ATAYAL projects include building a social network to connect Indigenous youth globally, and organizing events and courses to teach Chinese-Taiwanese about Indigenous culture and its contributions to local and global society.

However, maintinng and revitalizing languages in the hills or sparsely populated coastal East Taiwan is one thing. But many of the universities, jobs, and opportunities are in the big cities – Kaohsiung, Taichung, and the capital, Taipei. Many families, such as that of my friend, move into the cities for work or school, and it is there that they become assimilated into mainstream, Mandarin-Taiwanese culture. It is Mandarin that is needed to get a job and participate in society, and as urbanization continues, the place of aboriginal languages in society gets smaller and smaller.

We need more people like Dylan, my Truku host, who teaches physical education at a rural school, the attendees of which are, he told me, mostly aboriginal children from various tribes. The coursework is almost entirely in Mandarin, and through the government has recently implement place-based education that allows for 40 minutes of local culture and language instruction, it is insufficient.

Dylan tried to change that. "I tell my students to speak their language, in school, amongst themselves, because it is important that they use it."

In the end, what will really make the difference is the pride of people like Dylan, and other Aboriginal people, in their culture and language, and the ability to use that language in their lives. The language loss I saw at my friend's wedding, and the efforts of people like Dylan and organizations like ATAYAL are happening simultaneously, two forces moving in different directions. A lot of progress has been made this decade, and the attitude of non-aboriginal Taiwanese, who, for the most part, genuinely respect and want to maintain the culture and language of their Indigenous kin. If we work together, the current generation will not be the last to speak the Austronesian languages in Taiwan.

--Nithin Coca is a freelance writer who focuses on cultural, economic, and environmental issues in developing countries with an aim at building channels of communication and collaboration around common challenges.