By Gerard Tiwow (Minahasa)

“Nowhere in Indonesia has the old culture so fast and so completely disappeared as in the Minahasa” – Hetty Palm, Ancient Art of Minahasa (1958)

Minahasa is not originally the name of a single Indigenous community, but rather a term referring to a union of Tribes residing at the northernmost tip of Sulawesi, Indonesia. From a linguistic perspective, the word Minahasa is rooted in esa, meaning “one.” This root later evolved into ma’esa or, in the ancient southern dialect, mahasa, meaning “becoming one,” and eventually into mina’esa, which means “has become one.”

The earliest known historical record of the term Minahasa is from 1780, in reference to the unification of mountain-dwelling Tribes in their resistance against foreign coastal groups. In pre-colonial times, Minahasan society did not possess a single name to describe the entirety of its civilization. Instead, each community shared a common understanding of their origin as descendants of To’ar and Lumimu’ut, regarded as the first humans of the land. This shared ancestry formed the cultural foundation that later enabled unity among distinct Tribes.

The original center of Minahasan civilization is believed to be located in a place known as Tu’uz in Tana’ (the base of the land), which today lies within the South Minahasa. This early society is known as the Malesung civilization, a name derived from the area’s basin-like geographical formation. Stone mortar basins, which were used extensively for both domestic and ritual purposes, were central to daily life and cosmology, reflecting a close relationship among landscape, technology, and belief.

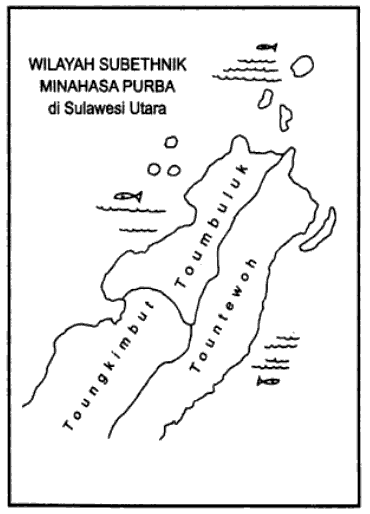

The Malesung civilization consisted of three ancient Tribal groups: the Toumpakewa, who inhabited the southern and southwestern regions, the Tombulu’, residing in the western and northwestern highlands, and the Tountéwoh, who lived primarily in the eastern areas.

Ancient Minahasan Tribal Map

The Toumpakewa were named for the abundance of pakewa trees in their territory. Among the Tombulu’ People, they were also called Toungkimbut, a term referring to the tight loincloth worn by men, which accentuated the form of the male genitalia. The Tombulu’ themselves derive their name from tou um wulur, meaning “people of the mountains” or “people of the hills.” Meanwhile, the Tountéwoh were named for their close association with lakes, where tiwoho plants grow abundantly, hence tou un tiwoho, or “people of the tiwoho.”

Over time, the name Toumpakewa/Toungkimbut evolved into Tontémboan, derived from tou un témboan, meaning “people who look downward from above.” While the Tontémboan and Tombulu’ maintained their respective territories, the Tountéwoh later divided into Tondanouw and Tonséa’ groups. Subsequent generations saw further divisions, as the Tondanouw separated into Tondano (Tolour), Tonsawang, and Pasan-Bangko. Pasan-Bangko later split into Pasan and Ratahan, and eventually Ponosakan. These processes of differentiation reflect population movement, ecological adaptation, and shifting political organization over centuries.

Today, there is broad agreement that the Minahasa consist of eight Indigenous Tribes: Tombulu’, Tonséa’, Tondano, Tontémboan, Tonsawang, Pasan, Ratahan, and Ponosakan. Some contemporary discourse includes the Bawontéhu’ and Bantik Peoples within the Minahasan framework—a position that is highly controversial because the Bawontéhu’ do not share the same ancestral lineage and are historically known as refugees from Manadotua Island, once the center of the Bawontéhu’ Kingdom. The Bantik, meanwhile, are a seafaring people, whom some historians believe originated from the northern islands. Longstanding land incursions into mountain territories led to repeated conflicts between the Bantik and upland communities.

Today, the term Minahasa is often used interchangeably with individual Tribal identities. Among fellow Minahasans, people typically identify themselves by their specific Tribal affiliation. However, when interacting with non-Minahasan communities, they commonly identify collectively as Minahasan.

Contemporary map of the Minahasa Peoples. The Bantik area (in green) is considered a contested area with the Tombulu’.

Understanding Minahasa: Social Structure

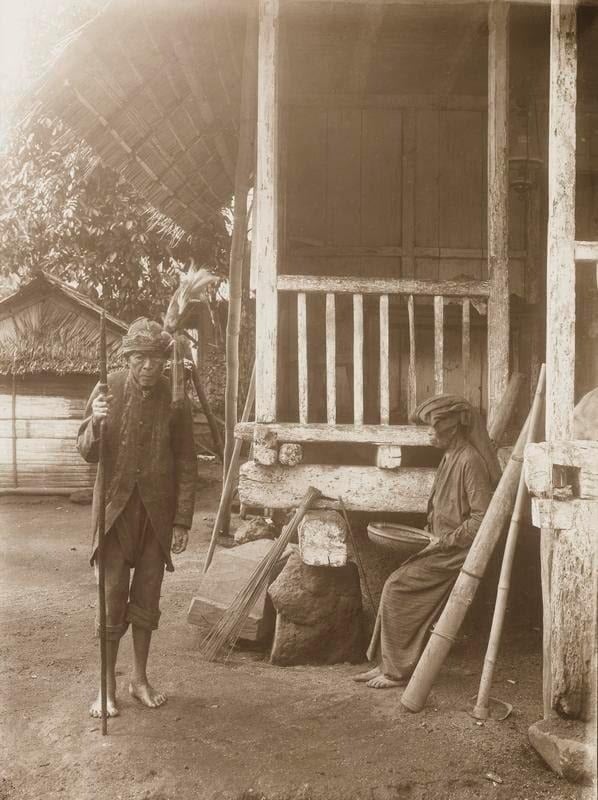

Minahasan society has never recognized a single ruler or centralized authority. The most basic social unit in Minahasa is the awu, which literally means “smoke.” An awu consists of a nuclear family, with each family required to have its own pa’lutuan (kitchen), as the smoke rising from the hearth symbolizes life, continuity, and autonomy. Several awu form a taranak, which can be understood as a clan or extended family group. Each taranak is guided by an Elder known as pa’éndon tu’a, meaning “the one where we seek the old wisdom.” While this figure is sometimes described as a leader, their authority is not coercive or hierarchical. Instead, the pa’éndon tu’a holds the highest advisory and decision-making responsibility based on experience, moral authority, and communal trust.

A pa’éndon tu’a and his wife.

A group of taranak forms a wanua, or village. Similar to the taranak, the wanua does not operate under a formal government system, but instead follows a functional leadership structure. Each wanua is led by a Tona’as Umbanua, who serves as the highest political authority. Supporting roles include the tétérusan or tona’as paséké’an (war commander), the wali’an (religious and ritual leader), and other tona’as responsible for specific communal affairs such as agriculture, hunting, water management, and land stewardship.

The term tona’as originates from the words tou (person) and ta’as (strong), reflecting strength not merely in physical terms, but also in wisdom, responsibility, and moral integrity. Each tona’as holds a distinct mandate assigned by the Tona’as Umbanua, reinforcing the functional nature of Minahasan leadership.

Several wanua may form a walak. However, the wanua is the highest sovereign unit in traditional Minahasan society, as it holds authority over both people and land. The walak functions primarily as a coordination unit rather than a governing authority. Leadership at this level is held by the Ukung Tu’a, meaning “the bearer of old wisdom.” The Ukung Tu’a plays a role similar to the pa’éndon tu’a, but on a broader social scale, serving as an advisor and mediator rather than a ruler.

Groups of walak that share the same language and ritual traditions form a larger cultural unit known as pakasa’an. In contemporary understanding, Minahasans generally equate the concept of suku (Tribe) with the pakasa’an level, while wanua or walak may be considered Indigenous communities. There is no singular authority governing a pakasa’an, though certain respected figures from influential walak may exercise moral or cultural influence across the wider group.

This decentralized system was often misunderstood by European observers. During early European contact, colonial writers frequently mischaracterized the Ukung Tu’a as a king or ruler, imposing foreign political concepts onto a fundamentally non-hierarchical Indigenous system. The Dutch colonial period severely disrupted Minahasan social organization, transforming a functional and relational structure into a rigid administrative hierarchy. Colonial authority was centered in the Keresidenan Manado (Manado Residency), led by a Dutch-appointed Resident. Below this were administrative units such as afdeeling and onder-afdeeling.

Colonial authorities appointed Ukung Tu’a as heads of onder-afdeeling, effectively redefining Indigenous leadership roles to fit colonial governance structures. In the contemporary Indonesian administrative system, the onder-afdeeling roughly corresponds to the district. However, these imposed boundaries rarely align with traditional walak territories, resulting in the fragmentation of Indigenous land, authority, and social cohesion.

The Decline

Within the Minahasan belief system, the wali’an (priest or priestess) holds a transcendent responsibility of connecting the living community with the deity, the ancestors, and the unseen forces that sustain balance among humans, land, and cosmos. The term wali’an means “accompaniment,” reflecting their role as spiritual guides who walk alongside the community through ritual, life cycles, and moments of crisis.

In traditional Minahasan society, every taranak or wanua possessed its own si ma’mu’is, or ritual headhunter. Contrary to popular misrepresentations that portray headhunting as random violence, ma’mu’is functioned within a cosmological logic tied to warfare, spiritual power, and social survival. One of the primary targets in inter-community conflict was the wali’an. The death of a wali’an was understood to be catastrophic—not merely the loss of an individual, but the collapse of the village’s ritual life. Without a wali’an, there was no one to lead ceremonies, communicate with ancestors, or restore balance after illness, disaster, or conflict. In this sense. The destruction of the wali’an meant the destruction of the wanua itself.

During the Dutch colonial period, wali’an were targeted for elimination. Dutch soldiers identified the wali’an as the backbone of Indigenous authority, knowledge transmission, and collective morale. Without them, colonial power could more easily dismantle Indigenous governance from within, without confronting armed resistance directly. The persecution of wali’an intensified with the spread of Protestant Christianity, which labeled Indigenous Minahasan spiritual practices as heretical, idolatrous, and even satanic. This framing justified widespread forced conversion and the systematic suppression of Indigenous religion. As wali’an were killed, silenced, or delegitimized, ritual life collapsed, leading to the erosion of cultural continuity and Indigenous identity. The disappearance of the wali’an marked the loss of oral knowledge, cosmology, medicinal practices, environmental ethics, and historical memory.

Minahasan Priestess Timbe’e Walukow from Sonder.

From the 19th century onward, Indigenous practices across all aspects of Minahasan life experienced rapid decline. One of the most visible examples is the Waruga burial system. In Minahasan cosmology, the soil itself is sacred. To bury the dead beneath the ground is considered an act of desecration and disrespect toward Makawalang, the deity dwelling within the earth. For this reason, the dead were traditionally placed above ground. This burial system represents thousands of years of cultural evolution and philosophical interpretation.

Waruga are not merely graves; they are eternal stone houses built to honor the dead and maintain harmony among the living, the ancestors, and the land. Each Waruga embodies complex symbolism, craftsmanship, and cosmological understanding. Contrary to colonial narratives, Waruga were carefully designed, sealed stone structures that did not contaminate the environment.

Under Protestant influence and colonial authority, the Waruga system was eventually banned under the pretense of public health and disease prevention, despite no historical record of epidemics arising from Waruga practices. In actuality, it was European contact that introduced devastating diseases. In the late 19th century, Minahasa suffered a massive cholera epidemic that wiped out approximately a quarter of the population. While the cultural practice blamed for disease had coexisted safely with Minahasan society for generations, colonial intrusion brought unprecedented biological catastrophe.

The final Waruga burial was recorded in 1928, marking the end of a funerary tradition that had defined Minahasan cosmology for thousands of years. With its disappearance came the loss of ritual knowledge, architectural wisdom, and spiritual philosophy encoded in stone.

Approximately 200 years of Dutch colonial rule in Minahasa, from the late 18th century until 1945, systematically dismantled Minahasan cosmology, social organization, and language. Functional leadership structures were replaced with rigid hierarchies, spiritual authority was criminalized or delegitimized, and Indigenous languages were marginalized through missionary education and colonial administration. What survived did so in fragments embedded in oral tradition, family memory, and scattered ritual remnants.

The disappearance of the wali’an is not an isolated historical tragedy, but part of a broader pattern of epistemicide: the deliberate destruction of Indigenous systems of knowledge. Understanding this history is essential not only for cultural recovery, but also for contemporary struggles over Indigenous rights, land, identity, and self-determination in Minahasa today.

Language Loss

The erosion of Minahasan culture is inseparable from the decline of its languages. Generations born prior to 1960 were still able to speak their respective Minahasan languages fluently. However, among subsequent generations, language transmission rapidly weakened. Today, many Minahasans can no longer speak—or in some cases understand—their ancestral language.

This decline was intensified by modernization and globalization, but its roots lie in earlier colonial and missionary policies. Indigenous languages were systematically displaced by Dutch, and later Indonesian, as languages of administration, education, and social mobility. Over time, speaking one’s Indigenous language became stigmatized. Some Minahasans internalized the belief that using their native language was a sign of being “backward,” rural, or “primitive,” an attitude that reflects deep colonial conditioning.

Although there have been efforts to reintroduce Indigenous languages into formal education, these initiatives have had limited impact. Language instruction is often symbolic rather than structural. It lacks standardized curricula, trained teachers, intergenerational continuity, and most importantly, daily practical use. Languages cannot survive solely as school subjects; they require social space, ritual function, and community legitimacy. Without these, classroom-based instruction becomes detached from lived experience.

The suppression of language is closely connected to the marginalization of other cultural expressions. In several Christian denominations, Indigenous dances, music, and ritual expressions continue to be labeled as pagan, heretical, or incompatible with Christian belief. This theological framing reinforces cultural shame and discourages younger generations from engaging with their heritage. As a result, language loss is accompanied by the disappearance of songs, chants, oral histories, ceremonial vocabulary, and cosmological concepts that cannot be translated into dominant languages.

When the Waruga burial system was officially banned, the destruction of physical heritage accelerated. Waruga were vandalized, dismantled, and repurposed. Stones from Waruga were used as tomb markers, gravestones, and even building foundations. This destruction was not merely material, but symbolic: a severing of ancestral presence from the landscape. Alarmingly, such acts continue today.

The persecution has extended beyond the destruction of Waruga. Lesung (traditional stone mortars), which hold deep cultural and ritual significance, have also been targeted. Recently, some were deliberately destroyed during live-streamed events accompanied by Christian prayer as public performances of religious purification. Such acts represent a continuation of the historical violence of the ritualized erasure of Indigenous culture under the guise of moral or spiritual correctness.

Together, the loss of language, banning of rituals, stigmatization of art forms, and destruction of sacred objects constitute a sustained assault on Minahasan Indigenous identity. Language loss in particular signals a deeper crisis not only of communication, but of worldview. Embedded within Minahasan languages are ecological knowledge, ethical principles, kinship systems, and cosmological relationships that cannot survive in translation.

The disappearance of Minahasan languages is part of a broader process of cultural disintegration driven by colonialism, missionary zeal, and modern structural pressures. Revitalization efforts cannot succeed unless they confront this history directly and restore language to its rightful place within ritual life, land relations, and community practice.

Waruga of Pangémanan being restored.

Post-Colonial Division

Although Indonesian independence marked the end of formal colonial rule, it did not restore Indigenous governance systems. Instead, Minahasa became subject to a centralized national administrative model that further marginalized traditional structures. In the aftermath of independence, Indonesia underwent prolonged political turmoil and state consolidation. During this period, the government adopted a standardized administrative system largely modeled on Javanese governance structures. This system divided territory into kabupaten (regencies), kecamatan (districts), and kelurahan (subdistricts). These categories were applied uniformly across the archipelago, and did not align with Indigenous social and territorial realities in Minahasa.

Kelurahan and desa occupy similar administrative levels within the national system, but are fundamentally different in structure and legitimacy. A kelurahan is administered by a lurah, who is appointed by a bupati (regent) or walikota (mayor) and functions as an extension of the state bureaucracy. In contrast, a desa is led by a Hukum Tua, who is elected directly by the people and retains a degree of customary legitimacy rooted in Indigenous governance traditions. This distinction is crucial, as the expansion of the kelurahan system effectively weakened local autonomy and displaced customary authority.

Today, Minahasan Indigenous territories are located within Sulawesi Utara, or North Sulawesi Province. Administratively, these territories are divided among the three cities of Manado, Tomohon, and Bitung, and four regencies: North Minahasa, Minahasa (Central), South Minahasa, and Southeast Minahasa. Each city and regency encompasses multiple Indigenous Tribal territories, often without regard for historical boundaries.

This administrative fragmentation has had profound consequences. For example, both Manado and Tomohon cities lie primarily within Tombulu’ territory, yet traditional walak boundaries overlap across multiple modern jurisdictions. The Walak Tombariri is divided among Manado City, Tomohon City, and Minahasa Regency. Such divisions disrupt customary land management, ritual coordination, and collective identity.

In Minahasa regency, at least two distinct Indigenous groups, Tondano and Tontémboan, are administered under a single regency framework despite differences in language, ritual practice, and historical governance. North Minahasa regency and Bitung city are the only administrative units that correspond largely to a single Indigenous group, the Tonséa’.

These imposed boundaries have not only fragmented Indigenous territories, but have also weakened intergenerational transmission of knowledge, customary law, and collective memory. Governance systems designed for administrative efficiency have proven ill-suited to sustaining Indigenous civilizations whose social organization is rooted in wanua, walak, and pakasa’an.

The Contemporary Path

Every January 3, the descendants of To’ar and Lumimu’ut gather at Watu Pinawéténgan, the “Rock Where the Dividing Was Made.” This site is regarded as the most sacred place in all of Minahasa. The carvings on the rock—anthropomorphic figures, animals, lines, and geometric forms—each carry layered meanings. At the center of the rock is the si’zang symbol, an inverted triangle formed by intersecting lines representing boundary, balance, and protection. It marks the moment when order was established and difference was acknowledged without division.

The Tumo’tol ritual.

Oral tradition recounts that the ancestors of Minahasa held three great assemblies at Watu Pinawéténgan. The earliest, known simply as the Pinawéténgan, is believed to have taken place millennia ago. This chronology is preserved in ritual poetry, where it is said that “thousands of years after mapa’amian (the northward journey), and thousands of years before the era of Waruga, we were already here.” The oldest carbon-dated Waruga, dated to around the third century BCE, supports this timeline.

During the first assembly, the ancestors reached two foundational decisions: Pinawéténgan u Nuwu (the division of languages) and Pinawéténgan u Posan (the division of rituals). These decisions formally established the Tribes of Tontémboan, Tombulu’, Tonséa’, Tolour/Tondano, Tonsawang, Ratahan, Pasan, and Ponosakan. A colonial interpretation places this event around the year 670 CE based on genealogical reconstruction, though this dating remains strongly contested.

In the present day, the annual gathering on January 3 continues this ancestral mandate. The assembly is widely regarded as the highest deliberative forum among Minahasan Indigenous communities. Rituals and communal discussions are held to address unresolved conflicts, restore harmony, and set collective intentions for the coming year. The ceremony is known as Tumo’tol un Ta’un, or Tumo’tol Ta’un Weru, meaning “Setting the Foundation for the Year,” or “Setting the Foundation for the New Year.”

Although Tumo’tol is a contemporary ritual formulation, it is deeply rooted in historical practice. During the Dutch colonial period, the introduction of the western calendar normalized New Year celebrations. In Pinabéténgan village, people traditionally visited the rock after New Year festivities, bringing flowers and resting near the hot springs down the hill. This was originally an act of leisure rather than ritual. In the early 2000s, Indigenous communities from across Minahasa began voluntarily gathering at Watu Pinawéténgan on January 3, transforming the occasion into a formal ritual. The reasoning was clear: if a new year is to begin, it must begin at the place where Minahasa itself was founded by seeking wisdom, balance, and blessing from the ancestors.

Each year, Watu Pinawéténgan is filled with thousands of people. The atmosphere is both solemn and joyful. The assembly becomes a space of reconciliation where hostilities are resolved, relationships renewed, and collective decisions made. It is not merely ceremonial, but profoundly social and political in an Indigenous sense.

Several tona’as from the Tombulu’ community attend the ritual, including Rinto Taroreh, who serves as both tétérusan and wali’an. The ritual opens with a chant:

“O Empung Walian, Opo Wananatas, témbone kai i mengaléy” (O Most Prosperous and Glorious One, O Highest God, look down upon us as we pray to You).

Offerings of betel nut, traditional liquor of cap tikus, saguer, and coffee, tobacco, boiled eggs, and rice are placed in a designated area, followed by the presentation of heirlooms such as swords, spears, and ancestral objects laid upon the sacred rock.

Ritual offerings.

Rinto Taroreh then calls upon the ancestral warriors of Toktokai:

“Makakuakualako, ampélé-pélénge ya mindéngané, mindéngan, sé waraney Toktokai e!” (Let me hear all your voices here, the spirits of the warriors of Toktokai!)

He chants, “I Yayat U Santi!” (Raise your swords!), a moment that sends a palpable shiver through all who are present.

Subsequently, the wali’an invites ancestral spirits to enter his body as a vessel for wisdom and guidance. Among those invoked are Kumokomba’, guardian of Watu Pinawéténgan, Tantumoitou, who determines human fate, Makawalang, who dwells within the earth, Muntu-untu, who inhabits the sky, and Siow Kuruz, the ancestor of nine-knee height. Through this invocation, ancestral knowledge is not simply remembered symbolically, but made present.

Ruma’mus Ung Gio’ procession.

The ritual then continues at the water site in a procession known as Ruma’mus ung gio’ (“Washing the face”). The water spring is believed to be the realm of Mio’io, the guardian of the boundary between life and the realm of complete nothingness. The washing is performed in three downward strokes, each accompanied by prayer, marking purification, renewal, and hope.

I so’so’ moma un dano, un ipi léwo’ wo u rawoy, genang weresi’ (Just as this water streams away, may your nightmares and weariness be carried off, let your heart and mind be cleansed).

I sezu’ momé un dano, katu’tu’a wo kalalawizen, genang weresi’ (Just as this water flows, may a good life and prosperity come to you, let your heart and mind be cleansed).

Mengalé-ngaléy uman pakatu’an wo pakalawizen, genang weresi’ (All that we ask is for a good life and prosperity, let your heart and mind be cleansed).

The history of Minahasa is not a linear narrative of disappearance, but a long struggle between continuity and erasure. For centuries, Minahasan civilization was systematically weakened through the targeting of spiritual leaders, the criminalization of ritual practices, the suppression of Indigenous languages, and the fragmentation of ancestral territories. Colonialism, missionary intervention, and post-independence state centralization each contributed to the erosion of cosmology, governance, and collective memory. What was lost was not merely cultural expression, but an entire Indigenous system of knowing, relating, and governing the world.

Yet, decline does not equate to extinction. Beneath layers of imposed structures and internalized stigma, Minahasan identity endured in oral traditions, ritual fragments, sacred sites, and family memory. The persistence of ancestral knowledge, even in fractured form, demonstrates that Indigenous civilization does not vanish: it adapts, waits, and re-emerges when conditions allow. The challenge facing Minahasa in the modern era is not the absence of tradition, but the restoration of coherence among land, language, ritual, and community.

In this context, Tumo’tol un Ta’un represents far more than a ceremonial gathering. It is a contemporary Indigenous response to centuries of disintegration, a deliberate act of cultural re-centering. By returning each year to Watu Pinawéténgan, Minahasans reclaim the place where difference was first acknowledged without division, and where consensus was established through ancestral deliberation. Tumo’tol functions as a living institution of Indigenous governance, spiritual authority, and ethical renewal, operating outside colonial and state frameworks while remaining fully present in modern life.

The ritual’s power lies precisely in its adaptability. Though its current form is modern, its foundations are ancient. Tumo’tol demonstrates that revival does not require rigid reconstruction of the past, but meaningful continuity rooted in ancestral values. Through prayer, deliberation, reconciliation, and communal presence, Minahasans transform ritual into a tool for healing historical trauma, resolving contemporary conflict, and renewing collective purpose. In doing so, they resist the narrative that Indigenous cultures belong only to history.

Ultimately, Tumo’tol embodies the Minahasan path forward—not a return to an imagined past, but the reactivation of Indigenous civilization as a living, evolving force. It affirms that after centuries of decline, Minahasan identity is not only surviving, but consciously rebuilding through land, memory, ritual, and unity. In setting the foundation for each new year, Tumo’tol also sets the foundation for an Indigenous future shaped by ancestral wisdom and self-determination.

--Gerard Tiwow is an Indigenous journalist and researcher belonging to the Tombulu' Tribe of the Minahasa Peoples in Tomohon, Sulawesi Utara, Indonesia, and a former CS Youth Fellow.