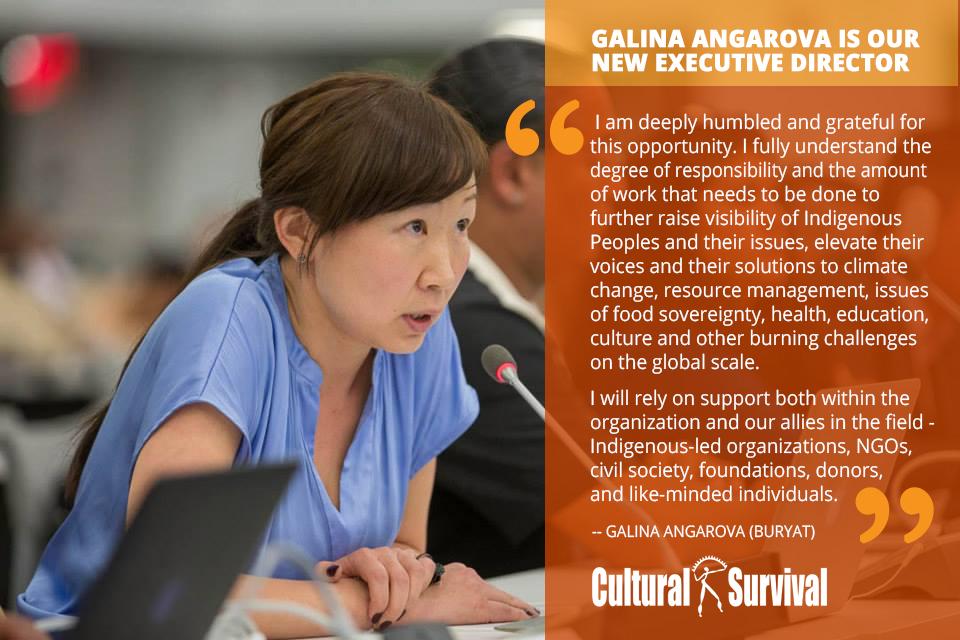

Being an Indigenous woman (Buryat), Galina Angarova is very familiar with Indigenous issues around the world. We look forward to Galina’s leadership which will support an increasing global presence and effectiveness of Cultural Survival’s ability to reinforce Indigenous goals of self-determination and self-governance.

Galina recently sat down to talk about a range of topics, including her work as an Indigenous rights advocate, as a foundation program manager, and her plans for Cultural Survival.

Thank you for reading, and as always, for your partnership. If you'd like to write a short note to Galina, please click here.

Cultural Survival: How did you get into this line of work, advocating for Indigenous Peoples?

Galina Angarova: I come from the Buryat Peoples who have lived in Siberia for millennia, on both sides of Lake Baikal, the deepest and largest fresh-water lake containing 20 percent of the world’s fresh water. I was born and raised in a community of about 400 people. I grew up eating wild berries, mushrooms, pine nuts, wild garlic, deer, and rabbit that members of my family would gather and preserve for harsh winters. My grandmother would tell me stories which encapsulated the wisdom of our ancestors and have been passed down for generations. I participated in our traditional ceremonies. I still vividly remember a time when I was five years old, when my grandmother took me to a ceremony on a wooden horse cart miles away from our village. I still recall the fire, the chants, and the prayers of the women in my clan. I grew up with a deep sense of understanding of our lifeways and belongingness to the land, to my people, and a deep love for my culture and for Mother Earth.

It was not until I was 24 when I first encountered the term “Indigenous Peoples.” Growing up in Russia, it was hard to really understand my own situation and the situation of my own people. It took leaving and living far away to understand the degree of both external and internalized oppression, colonization, and paralysis that my people and other Indigenous Peoples in Russia currently face.

I received a full scholarship to go to graduate school in the United States, in New Mexico. This is where I first met Native American Tribal members - Zuni, Navajo, and Acoma. I was blown away by their rich and vibrant cultures, the people, and the food. I made friends with local people and I learned that there were more similarities than differences between my people and Native Americans communities. Having a Native language, our own culture, land-use and management practices, belief systems, traditional ceremonies, traditional governance systems, and close relationships to Mother Earth--all these elements make Indigenous Peoples “Indigenous” and are rightfully included in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

My work in a professional setting as an advocate for Indigenous Peoples started when I joined San Francisco-based Pacific Environment in 2007. Even though the organization’s focus was on environmental issues in the countries of the Pacific Rim, we worked closely with Indigenous communities, specifically in the regions of Siberia, Russian Far East and, Russian Arctic and Alaska. I worked as a program associate for community-based initiatives and was responsible for campaign organizing, regranting, strategy development, and movement building among environmental and Indigenous organizations in Siberia and the Russian Far East. I was promoted to the Russia program director and started organizing global campaigns and representing issues of Russian Indigenous Peoples on the international level. In 2012, I joined the board of Indigenous Funders for Indigenous Peoples (IFIP) where I served as a board member for seven years.

CS: Tell us about your work with Indigenous Peoples on the ground?

GA: During my years with Pacific Environment, our team helped to build one of the most effective movements in Russia that works to protect both local people and the environment. This is what influenced my strongest belief that local and Indigenous communities are best equipped to protect their own environment. This is why I have always prioritized local needs and building relationships. One of the most successful campaigns I led was against plans to build a gas pipeline in Altai, an Indigenous republic in Western Siberia that borders with Mongolia, China, and Kazakhstan. Together with local Indigenous partners, we worked on a multi-tiered campaign that included several elements: targeting potential investors, protection of sacred sites and protection of rare and endangered species. We worked to bring in alternative energy such as solar, wind, and mini hydro-power, and created protected areas managed by Indigenous Peoples.

We conducted numerous exchanges bringing experts and activists from the United States and other parts of Russia who had similar experiences with large infrastructure projects. They met with local people and shared with their experiences of what happened to their land and people once the projects started - loss of biodiversity, corruption, pollution, disease, prostitution and so on. These conversations had a powerful effect on local people which resulted in local support for the campaign.

Other successful campaigns were protesting against a toxic paper mill on Lake Baikal, an oil pipeline that was supposed to be laid in the proximity to the northern shore of the Lake, an hydro-electric dam that threatened to flood thousands of hectares of forest and a settlement of five thousand Evenk people.

CS: Please tell us about your work with the Indigenous Peoples’ Major Group at the United Nations.

GA: As Tebtebba’s policy and communications advisor, my primary role was to serve as the Global Organizing Partner and Focal Point for the Indigenous Peoples Major Group at the United Nations from 2013-2016. My goal as the main negotiator for the constituency of Indigenous Peoples was to advocate the inclusion of key references to Indigenous Peoples in the outcome documents of Post-2015 Development Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals, World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction, and World Conference on Financing for Development. In my role, I organized preparatory meetings in Africa, Asia, and Latin America and gathered ideas from Indigenous representatives in these regions on key topics such as climate change, poverty, health, education, traditional knowledge, FPIC, etc. I participated in UN meetings in New York and Geneva, drafted interventions, and met with member states, UN agencies, and NGOs to strategize the best way to approach the negotiation processes.

During my time with Tebtebba I was also assigned to lead a team of Indigenous experts to provide input to ensure safeguards for Indigenous Peoples for the financial arm of the UNFCCC -Green Climate Fund. This all helped me to understand and navigate the system of the United Nations, to understand very complex issues pertinent to Indigenous Peoples, financial mechanisms, and negotiations. I was able to travel, meet with the constituency, study some legal cases and ultimately become an expert on Indigenous issues.

One of the most interesting projects during my tenure with Tebtebba was the project called Indigenous Navigator, a project funded by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and co-managed by a number of organizations such as Tebtebba, AIPP, IWGIA, Forest Peoples Program and several implementing local organizations. The project gathers data on Indigenous well-being using indicators that define the well-being such as health, education, land use, and traditional livelihoods. Pilot communities input the data and can monitor the level of recognition and implementation of their rights over the years. It is groundbreaking work that is gaining a lot of attention and I am proud to have been part of the team.

CS: Tell us about your time with the Swift Foundation?

GA: My most recent job was with Swift Foundation. As a program officer, I managed a portfolio of 65-75 partner-grantees in regions of Africa, South America, Canada, and the United States. I was responsible for managing relationships, conducting due diligence on prospective partnerships, reviewing reports and proposals, conducting site visits and periodic scans of the political, social and cultural landscapes in target regions to identify opportunities and trends in areas of interest such as: alternative energy, agroecology, Indigenous Peoples, extractive industries including mining oil, gas and industrial agriculture, microcredit, and integrated capital. I also provided program updates, research and analyses for the board, collaborated with peer foundations and institutions to enhance the effectiveness and reach of programs and represented the foundation in conference and meetings of the philanthropic community.

During my time with the foundation, I was able to increase the number of Indigenous-led organizations in the portfolio, strengthen connections to Indigenous communities and focus on Indigenous-led grantmaking, and advocated the shift toward more multi-year unrestricted grants. I also initiated the idea of an Institute on Philanthropy from an Indigenous Perspective, nurtured the idea in a small team, and rallied the Board to support it with a multi-year grant. The Institute is now thriving and is hosted under the umbrella of the International Funders of Indigenous Peoples.

CS: What are the major challenges Indigenous Peoples face today?

GA: Climate change is becoming the number one risk for Indigenous Peoples, as they are one of the most vulnerable populations and are disproportionately affected by its impacts. We are among the first to face the direct consequences of climate change. In the Arctic communities are suffering from the receding ice, changing weather patterns, increased storms, changes in species and animal behavior. In the high altitudes of the Himalayas, people depend on the seasonal flow of water from glaciers and unprecedented melting is resulting in more water in the short term, but less in the long run. Communities in Siberia and the Amazon are currently affected by the raging fires.

Secondly, Indigenous activists are targets of local governments, landowners, private security, poachers, mining companies, agribusiness and so on. The 2018 Global Witness report documented that it has never been a deadlier time to defend one’s community, way of life, or environment. Their latest annual data on violence against land and environmental defenders shows a rise in the number of women and men killed in the year 2017 to 207 - the highest total they have ever recorded. Indigenous defenders represent roughly 25 percent of the total. However, with Indigenous Peoples making up just 5 percent of the world’s population, they are massively overrepresented among defenders killed.

Finally, Indigenous People globally are facing diminishment of their human rights and rights to their lands, territories, and resources. Today, Indigenous Peoples are standing up against an immense force of international corporations, corrupt and openly hostile governments, and weak national legislatures on Indigenous rights. This global narrative promotes infrastructure development and conversion of nature and culture into commodities in places of biological and cultural diversity. Most biological and cultural diversity is located on the lands of Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous managed lands and territories span 24 percent of the planet’s surface and they are a home to 80 percent of the planet’s biodiversity. Indigenous Peoples have known and managed this diversity for millennia, and there is a lot to be learned from Indigenous Peoples for the sake of survival of the human species. The time is running out and we need to act now.

CS: What needs to be done to bring about solutions to these challenges?

GA: Working on Indigenous issues, I have traveled to far away corners of the world visiting Indigenous communities. Some are facing tremendous poverty and others are thriving. La Trinidad outside of Oaxaca, Mexico, is a forest community where Indigenous Peoples have ownership of lands and forests, operate a wood processing facility and a small furniture factory. Most importantly, they have government support and a contract with local schools to supply them furniture.

From my travels, I came to a conclusion that the key elements for those thriving communities are self-determination; ownership and access to their lands, territories, and resources; traditional livelihoods; ownership of capital; opportunities to build their own capacity; Free, Prior and Informed Consent; and legislative, technical, and financial support from their State governments and philanthropic institutions. These are the cornerstone elements of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the Declaration that thousands of Indigenous activists were fighting for, sometimes at the expense of their lives and the lives of their families.

Cultural Survival is in a unique position to address these issues having the experience and the reach that it already has. We need to support research and better understand and respond to climate impacts. We need to use traditional knowledge, Indigenous adaptation and mitigation strategies, and transform this knowledge and strategies into action. Research by the Rights and Resource Initiative, the Woods Hole Research Center and the World Resources Institute shows that areas managed by Indigenous communities and other forest-dependent Peoples account for at least 24 percent of the carbon stored above-ground in the world’s tropical forests. Traditional agriculture and agroecology is yet, another way to store carbon. Indigenous peoples have known this and used this knowledge for centuries. It needs to be amplified.

We need to build capacity of Indigenous communities and support them in asserting their rights. We need to strengthen community leadership and technical know-how, create and disseminate educational resources to advance human and Indigenous rights. We need to connect Indigenous networks and be informed about events on the ground. We need to tell stories, increase media attention and expose government and industry abuses. The most powerful stories come from people themselves. Walrus hunters in Nome, Alaska, a few years ago told me that they keep losing their husbands and sons to harsh hunting conditions which have worsened due to climate change.

People matter, we matter, the voices of Indigenous people who manage 24 percent of this planet's surface, matter. We are standing up against this immense force of corporate greed and corruption, however, if we ignite the flame from one person to another, we will organize a global movement which will counter the existing status quo.

CS: Do you already have a vision for the organisation? Please share your goals with us.

GA: I would like to stress on the importance of a common vision and buy in from all the members of the board and staff. Even though I do have my own aspirations and some elements of the vision, I believe that every single member of the Cultural Survival team should have a voice and that the vision of the organization should be based upon consensus.

Another goal is building a successful program for Indigenous women and girls and addressing issues at the intersection of Indigenous women and climate change, traditional knowledge, environmental and human rights defenders, and elevating the role of Indigenous women in traditional governance systems and decision-making at local, national, regional, and international levels.

Among the long-term goals, I would name elaborating a message and programming around Indigenous food systems and nutrition, growing the field of Indigenous-led philanthropy, and growing our own funds within Cultural Survival, and building alliances with other movements and networks. Our work would not be possible without the support of our friends and allies. We have launched the new Leadership Transition Fund to support Cultural Survival to go through the transition period, build on our successes, guide the organization to new work to address the realities of the ever changing world, and come up with an updated strategic direction. I invite you all to support our joint efforts and donate to the Leadership Transition Fund and ensure the success and longevity of Cultural Survival.