By Alexandra Carraher-Kang

On January 14, 2020, over 100 individuals, including members from other Indigenous Tribal Nations, stood with the Shinnecock Indian Nation in part of an ongoing protest against development on sacred burial grounds in New York. Located in Sugar Loaf, a designated critical environmental area, the development of a single-family, two-story residence with a three-car garage was approved by the town Southampton. However, the applicant did not inform the Shinnecock Nation of its plans.

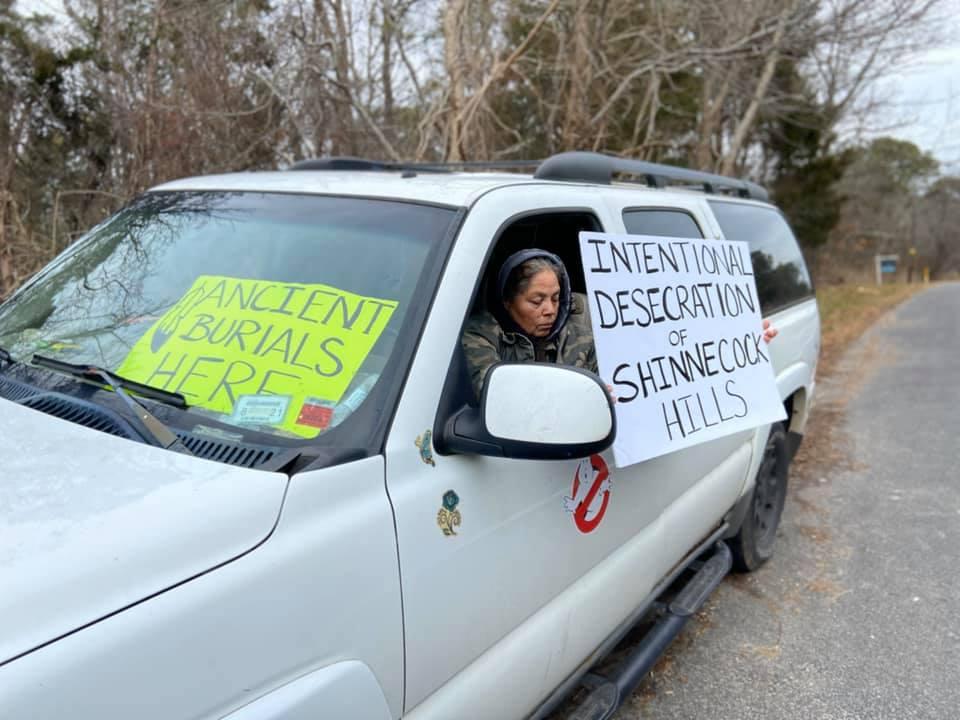

In 2018, during construction on Hawthorne Road in Shinnecock Hills, a Native American grave was desecrated when remains were dug up. Ever since, to quote Shinnecock Nation Vice President Lance Gumbs, “a verbal commitment [was] made to notify the Nation of any future disturbance in our sacred Shinnecock Hills while work was being done to pass legislation that would protect our sacred sites that have been listed on the Shinnecock Hills’ sensitive site map with the town for years.” Despite the formation of a Stewardship Committee to craft legislation to protect Shinnecock lands, the Committee met only twice in 2019. “We’re being told...that they want to work with us,” Shinnecock Tribal Member Chenae Bullock explained to Cultural Survival, “but the actions are showing something different,” and when governments ignore their past promises, it becomes “intentional desecration.”

The ongoing construction marks how, Gumbs stated, “the words of the town leaders are meaningless when it comes to keeping their promises to the Shinnecock Nation.” In the words of Shinnecock Tribal member Tela Troge, “The town of Southampton should follow their own laws. They need to notify us so that we can tell them this is a very sensitive site, this is a very important site, and you can’t desecrate it.” Speaking about longtime Shinnecock activist Becky Hill, Bullock put the reality bluntly: “She wasn’t even notified.” If the correct procedure had been followed, the Shinnecock Nation has argued, they would have pushed for soil tests in order to prove the Sugar Loaf site’s existence as a burial ground. But, since neither the applicant nor the town informed Shinnecock Nation of the building plans, there was little the Nation could do.

Despite meetings between town officials and Tribal leaders over crafting legislation regarding such processes, there remains little consensus. Moreover, Southampton Town Supervisor Jay Schneiderman stated, “One of my biggest concerns is that if we come up with too onerous of a process, that developers – it would be unethical and potentially illegal – but my concern is that they would look the other way. And push the bones in a different direction, bury them, pretend like they never saw it.”

When lands are taken and remains are excavated, these same remains must be reburied by the Nation. “Just in the last year alone, over 100 remains that were taken across the East End of Long Island were repatriated back to us and just in the last couple of weeks we’ve had to rebury 106 of our ancestors’ remains that were repatriated for us,” said co-chairman of the Shinnecock’s Grave Protection Warriors Society Shane Weeks. It’s a painful process, too, with Shinnecock Tela Troge calling it “a trauma we have to relive every single time this [development on sacred lands] happens, and we put up a fight every single time this happens, but it shouldn’t be this way.”

Since December 28, when Shinnecock Tribal members realized that digging was occurring on ancestral lands, rallying against the Sugar Loaf construction has taken place. “This is a joining of forces to bring our message to the Town of Southampton, State of New York, and to all the developers who come out here and desecrate in their rush to construction,” said Shinnecock elder Margo Thunderbird. “This is a demonstration of determination and we are determined to stay the course of resistance until ‘not one more acre’ becomes our rallying cry and our collective reality.”

“We are not protestors, we are protectors,” Thunderbird stated. Other than land and remains, those protesting are protecting their entire historical legacy; Bullock said, “If they desecrate our skeletons, that’s a way of erasing us” and removing the Tribe from history. In the meantime, Bullock explains that, “We need to ensure that local governments are doing their due diligence,” because the developers are still going to build, “but what they don’t know is that these lands are ancestral burial grounds.”

“I’ve watched my elders fight the same exact battle on the same exact highway,” Bullock continued. “This fight isn’t from two weeks ago, from 25 years ago, from 100 years ago. This fight is 400 years old...There has to be some type of resolution. We’ve done everything. The next step is a decision.”

Although the January 14 protest was successful, with no construction occurring that day, protests are expected to continue until building and construction on the site end. “No Indigenous person needs permission to fight for what is right,” Bullock declared.

Photos courtesy of Chenae Bullock.