By Ishmael Hope, Sealaska Heritage Institute

“Át Khuwaháa haa yoo xh’atángi wutusaneixhí.” “The moment has come for us to save our language.”– Joe Hotch, Gooxh Daakashú

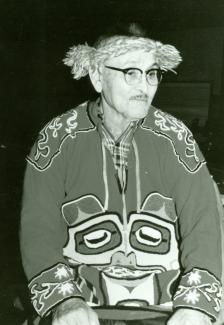

In 1980, the Sealaska Corporation brought together Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian Elders in Sitka, Alaska, for a gathering of discourse, stories, and traditional songs and dances in the first Sealaska Elders Conference. During one evening, Charlie Joseph, Khaal.átk’, an Elder of the Kaagwaantaan clan, led traditional performances of Tlingit songs and dances, many of which, he told his peers, had not been seen or heard in many years. He asked his Elder peers to have patience and forbearance for the young dancers, as they were learning and could make mistakes. The Elders ended up overwhelmingly embracing Charlie Joseph’s leadership. In thanking Joseph, William Johnson, Keewaaxh.awtseixh Ghuwakaan, said that, “I ítnáxh ghunéi kghwa.áat.” “People will begin to follow your example.” (Haa Tuwanáagu Yís: Tlingit Oratory, edited by Nora and Richard Dauenhauer, 1990.)

The people really did follow the example of those Elders at the Shee Atika Hotel in 1980. That conference led to the creation of the Sealaska Heritage Foundation, later to be renamed the Sealaska Heritage Institute (SHI), with a mission to perpetuate and enhance Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian cultures. In 1982, following the example led by Charlie Joseph and other Elders who were instructors in schools across Southeast Alaska, SHI created the biennial Celebration, a large gathering of Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian traditional singers and dancers. It has grown to host over 2000 traditional dancers and 3-4000 visitors who take in all the festivities and rich culture.

However, as George Davis, Kichnáalxh, noted at the 1980 conference, “Ch’a yéi gugénk’ áwé a kaaxh shukaylis’úxh haa tlagu khwáanx’i aadéi s khunoogu yé.” “We have uncovered only a tiny portion of the way our ancient people used to do things.” He also said, “Tsu héidei shugaxhtootáan yá yaakhoosgé daakeit haa jeex’ a nakh has kawdik’éet’.” “We will again open this container of wisdom that has been left in our care.” There was so much more of this “container of wisdom” to be shared, and SHI’s Council of Traditional Scholars and Board of Trustees recognized that much of that deep knowledge of Tlingit culture and worldviews was embedded in the Tlingit language. In 1997, the trustees adopted language restoration as the foremost priority of SHI. Revered Tlingit Elder Walter Soboleff, for whom SHI’s new cultural center is named, told his Elder peers, “Yak’éi áyá has du ée tududasheeyí wáa sá khóo at dultóow yá yoo xh’atánk yoo xh’atángi has du éexh yáa uháan Lingít xh’éináxh yoo xh’atula.átgi.” “It would be good if we help whoever is teaching the Tlingit language, those of us who speak Tlingit.” (1996, KTOO Radio Conversations, edited by Keri Eggleston, et al.)

These and many other words of the Elders deeply inform the work of SHI, and continue to inspire and motivate leaners today. It was like they planted little seeds, embedded pockets of knowledge and meaning in our hearts and minds, meaning which would only deepen within us as we matured and were in need of the wisdom that was left in our care. Guided and encouraged by the Elders, SHI, over many years of advocacy and development, joined with many organizations, Southeast Alaska school districts and the University of Alaska Southeast in developing a comprehensive, region-wide network of Tlingit language programs, learners and teachers. There are now over 500 students of the Tlingit language in the Juneau School District, for example, and many teachers who dedicate their lives to learning and passing on their knowledge of the language. Many of these teachers received scholarships from the Sealaska Corporation, attended SHI’s language immersion camps, and have always been supported by SHI as their efforts bolstered SHI’s mission and goals. It is truly a community effort. Additionally, SHI hosts a Tlingit Language Master Apprentice Program, currently in its first year, which supports Tlingit language immersion for six master-apprentice teams in three Tlingit communities. The teams will speak at least 260 hours of Tlingit together over the course of three years. As SHI President Rosita Worl said during the launching of the program, “All languages reflect world view. And there is a lot of knowledge and experience embedded in that language. And for our human society that’s been around for thousands and thousands of years we want to be able to capture that knowledge.”

SHI also documents hundreds of hours of Tlingit language audio recordings and texts from its extensive archival collections. We most recently completed a National Science Foundation project that produced transcriptions and translations of 31 Tlingit language texts. Tlingit linguist James Crippen estimates that less than one percent of the total available Tlingit recordings are transcribed and translated, so this project adds significantly to the body of work for study. The greatest stories, along with everyday conversations, were documented. Students of the language can now mine the texts for stories of the Migration and Great Flood, for Xh’a Eetí Shuwee Kháa, Slop Bucket Man, and for funny conversations among elderly Tlingit women, or passionate advocacy for subsistence or the Tlingit language. The tiny portion of Tlingit knowledge that we have uncovered is slowly beginning to unwrap for us, available for the eager and dedicated learner.

The Sealaska Heritage Institute also stood with Tlingit Elders, students and faculty of the University of Alaska Southeast, and many others, Native and non-Native, in advocating for the passage of the historic state House Bill 216, which officially recognizes 20 Alaska Native languages as equal in standing with English. Advocates for the bill were passionate testifiers and lobbyists, eventually hosting a sit-in at the Capitol building lasting from mid-day to 3:30 am on April 21, when the bill finally passed to a great cheer of the packed galleys. With the signing of the bill into law by the governor, Sean Parnell, Alaska, with Hawaii, will become one of the two states that recognize Native languages as “official languages of the state.” This is one of the civil rights struggles of our times. Our world is in our language, our breath of life. We are truly equal when our particular, unique container of wisdom—haa yoo xh’atángi, our language, haa khusteeyí, our way of life—is acknowledged, honored and respected.

The Elders always gave us this strength. Sometimes we didn’t even fully comprehend what we were told until it came back to us like a vision of strength and forbearance that helped us to continue on. Elder Nora Dauenhauer tells Tlingit students that the Elders told all kinds of stories to people of all ages. No one told children’s stories. Everyone heard the complex, deeply layered, sophisticated, beautiful stories. Nora and her scholar husband, Richard, often mention that people “grow into it.”

In one of the most popular stories of Yéil, Raven, the Raven is said by some to have stolen the sun, moon, stars and daylight from his grandfather, Naas Shagee Yéil. The way that Austin Hammond, Daanawáakh, told it, however, was that “Haa dachxhánx’i yán áyá tusixhán.” “We love our grandchildren.” The Raven’s grandfather gave him the things he most treasured, even at the risk of losing it. The Raven opened those boxes and let free much of the universe, the material of life. It’s nothing less than the universe that we’re opening when we open the container of wisdom, given to us from the love of our grandfathers and grandmothers.

“Tsu khushtuyáxh daa sá yaa tushigéiyi át

du jeedéi yatxh ghatooteeyín

haa dachxhánxh siteeyi kháa.”

“Even those things we treasure

we used to offer up to them,

to those who are our grandchildren.”

- Charlie Joseph, Khaal.átk’