Between the Santa Marian earth and sky is a backstrap loom on which the history of people in this space is woven. The first shapes formed on this loom are Chumash, people who came from islands and established varying groups on the now Californian coast. The next people are woven into this space through the force of Spanish and Catholic seizure of Indigenous lands, then through the birth and growth of Mexico, through what the settlers of the United States call manifest destiny, and finally through the migrational currents that eventually carried Na Ñuu Savi from their ancestral space to ancestral Chumash territory.

Santa Maria is an agricultural city located in northern Santa Barbara County on the Central Coast of California. It is the second home of Na Ñuu Savi migrants from Yucha Nchaa (Santa Cruz Mixtepec) in the municipality of Ñuu Xnuviko (San Juan Mixtepec), Oaxaca. This is a reflection on the shared history between Na Ñuu Savi (People of the Region of the Rain) and Chumash from the origin of their respective homelands in what are now Mexico and the United States. It is not a definitive representation of Chumash and Na Ñuu Savi history given the generic use of dates to describe these histories. Rather, this reflection is meant to sketch the shared colonial influences and their legacies on those communities and estimate time frames related to them.

Chumash and Na Ñuu Savi History

Chumash territory encompasses most of the area between what is now Malibu and lower San Luis Obispo County, including the Northern Channel Islands off the coast of Santa Barbara. Like in Oaxaca, the home state in Mexico where my parents were born, the names of towns and cities in California are echoes that originate from a time before European arrival on Indigenous lands, resisting the pressure to be silent so they can be heard in the present. Pismo Beach (from Pismu - tar) and Lompoc (from Lum Poc - stagnant water or lagoon), cities on the northern end of the central coast of California, are names rooted in the history of Chumash lifeways. These place names, along with cave paintings found in the area, oral histories passed down to living Chumash relatives, crafts, and other traditions persisting Indigenous erasure, weave Chumash pasts, presents, and futures in California.

In Western Oaxaca and its adjoining regions in Puebla and Guerrero that make up Ñuu Savi (The Region of the Rain, La Mixteca) the nivi (people) of that region weave their own presence across time and space. We trace this presence through oral histories, historical records written using the writing system of Na Ñuu Savi, place names, architecture designed and built by our ancestors, preserved crafts, and other evidence that empower our futures despite continued pressure to sever us from our traditions and history. When the Spanish seized the Indigenous territories in what they called New Spain, they seized and disrupted networks of Indigenous lifeways where Na Ñuu Savi and Chumash had an advanced presence thousands of miles away from each other.

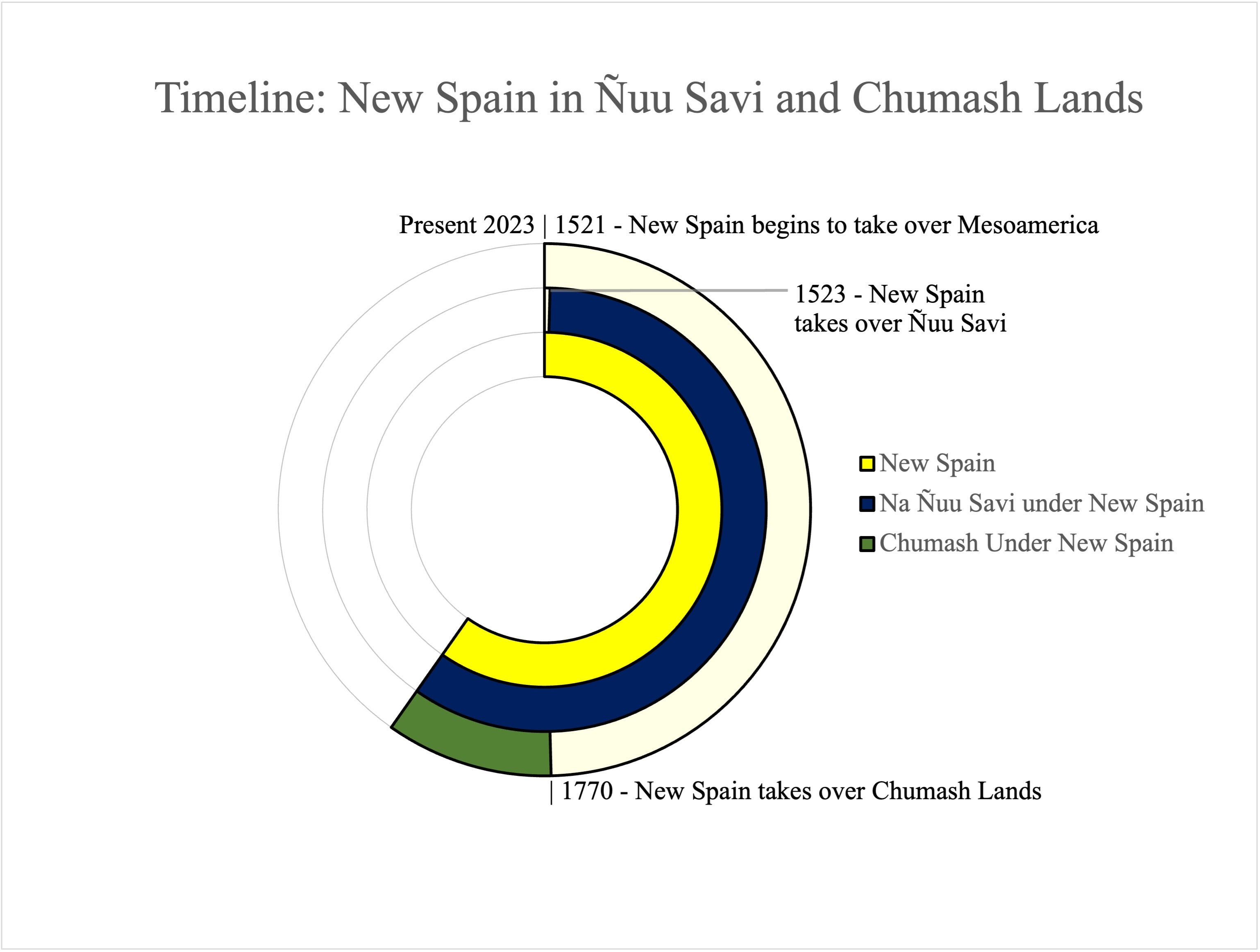

Timeline by Claudio Hernandez.

Chumash people have been resisting the takeover of Indigenous lifeways since the arrival of Spanish settlers in 1770 as these settlers expanded the Northern entity known as New Spain. In New Spain, Spanish people controlled Chumash lifeways while they also controlled the lifeways of Na Ñuu Savi, whose conquest occurred on the southern end of New Spain in 1523, 247 years before the arrival of Spanish people on Chumash territory. These lifeways came under the influence of Mexico in 1821, until California was ceded to the United States in 1848 following the U.S.-Mexican war that resulted from U.S. encroachment of Mexican land.

Na Ñuu Savi and Chumash, who were under the influence of the same colonial entities at the same time for 78 years (1770-1848), would exist in the same space again 112 years later when the first pueblos from Ñuu Savi began populating California in the 1930s following economic opportunities in the state’s developing agricultural industry, forging pathways for survival in the violent push/pull of capitalism at an international scale. Na Ñuu Savi arrived in the United States having experienced the compounding violence of Mexico’s anti-Indigenous development since their defeat by New Spain. This is the context my parents migrated with when they arrived in Santa Maria from Yucha Nchaa in 1993.

New Spain

When New Spain began to settle Chumash territory, Ñuu Savi had already been absorbed into the settler nation for 247 years. Although certain groups of Na Ñuu Savi continued to fight against the Spanish, many groups, often led by caciques (Na Ñuu Savi elites), surrendered and negotiated alliances amongst each other, leading to the preservation of much of the culture. However, when the Spanish absorbed Ñuu Savi into its territory, it began a series of events that would force Na Ñuu Savi to leave their homeland in large numbers. These events were driven by Spanish expansion, racism, and extractivism, exemplified by their grab of Indigenous territories, the dehumanization of Indigenous people, and the stealing of resources connected to Indigenous lifeways to fuel the lifeways of Spanish settlers and their descendants.

To settle Ñuu Savi, Indigenous people were congregated into towns so their land could be used to grow plants and raise animals for consumption. The overgrazing of those animals wiped out much of the native vegetation in the area and began to erode the soil. European agricultural techniques would loosen the soil further until the land was uncultivable. The settling of San Juan Mixtepec happened around 1567, and when land became uncultivable there, the people began to shift their locations to find work, returning more than 50 years later once the land had recuperated in the 1620s. The population in Mixtepec boomed later on because the land had not eroded as extensively and was plentiful. As shown in San Juan Mixtepec, the congregation of Na Ñuu Savi into towns marks a long legacy of forced displacement by the Spanish and their descendants.

As a branch in the system of Spanish settlement, the churches established in Ñuu Savi would participate actively in the mistreatment of Indigenous people. When Dominican friars arrived, the evangelization of Na Ñuu Savi became a process from which Nivi Savi were violently forced to reshape their religion, history, and language to assume Spanish customs. Books were burned, people were beaten into abandoning their beliefs, sacred buildings were destroyed, and their pieces were used to build Dominican places of worship. Through a spectrum of triumphs, Na Ñuu Savi were able to carry forward many ancestral ways into future generations despite the losses they faced.

To collect tribute, an existing system was appropriated. Peasants from Ñuu Savi would send tribute to caciques, caciques would ensure the production of the tribute by supervising the peasants, and Spanish authorities would collect the tribute from caciques, leaving a good share for them. Through the New Laws of 1542, New Spain gained further control of Indigenous lifeways by giving more land to Spaniards, thus creating even more dependence on Spanish authorities and breaking the system of reciprocity with the natural world that Na Ñuu Savi had practiced even under Aztec rule. Peasants were forced to work mines, farms, and ranches belonging to these Spanish authorities who overworked laborers. Along with the brutality of being overworked and stripped of their cultural identity and physical lifeways, Na Ñuu Savi suffered from foreign diseases brought by the Spanish. When New Spain expanded into what is now California in the 1700s, Na Ñuu Savi had experienced a large decline in population, culture, and language.

Between 1770-1821, as New Spain took over Chumash territory, Chumash people had similar experiences as the Na Ñuu Savi. During this period, Chumash were congregated using the mission system where their land was placed under the care of Franciscan authorities who were trusted with acculturating Chumash, using them and their lifeways for labor and resources that would sustain settlers of the area. In the changing landscape of their home, Chumash were forced to look towards the missions for survival. Within 34 years (1772-1806), a majority of Chumash groups had moved under the Franciscan mission system.

Chumash people who lived on land that is Santa Maria were likely moved to La Purisima Mission near Lompoc in 1787. Chumash also experienced losses in population, culture, and language despite their own resistance, even after Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1821 and Mexico’s takeover of the California missions in 1834, totaling 64 years of Spanish-Catholic influence on Chumash territory. Much of Chumash land would remain fertile for years to come, unlike in Ñuu Savi. By 1821, the people of New Spain had taken over and transformed Indigenous networks between its southernmost boundary in Costa Rica and its northernmost boundary in California, several islands in the Caribbean, and islands in the Philippines.

— Claudio Hernandez (Na Ñuu Savi/Mixtec) is a 2022–2023 Cultural Survival Writer in Residence. He is working on other writings reflecting on the shared history between Na Ñuu Savi (People of the Region of the Rain) and Chumash.

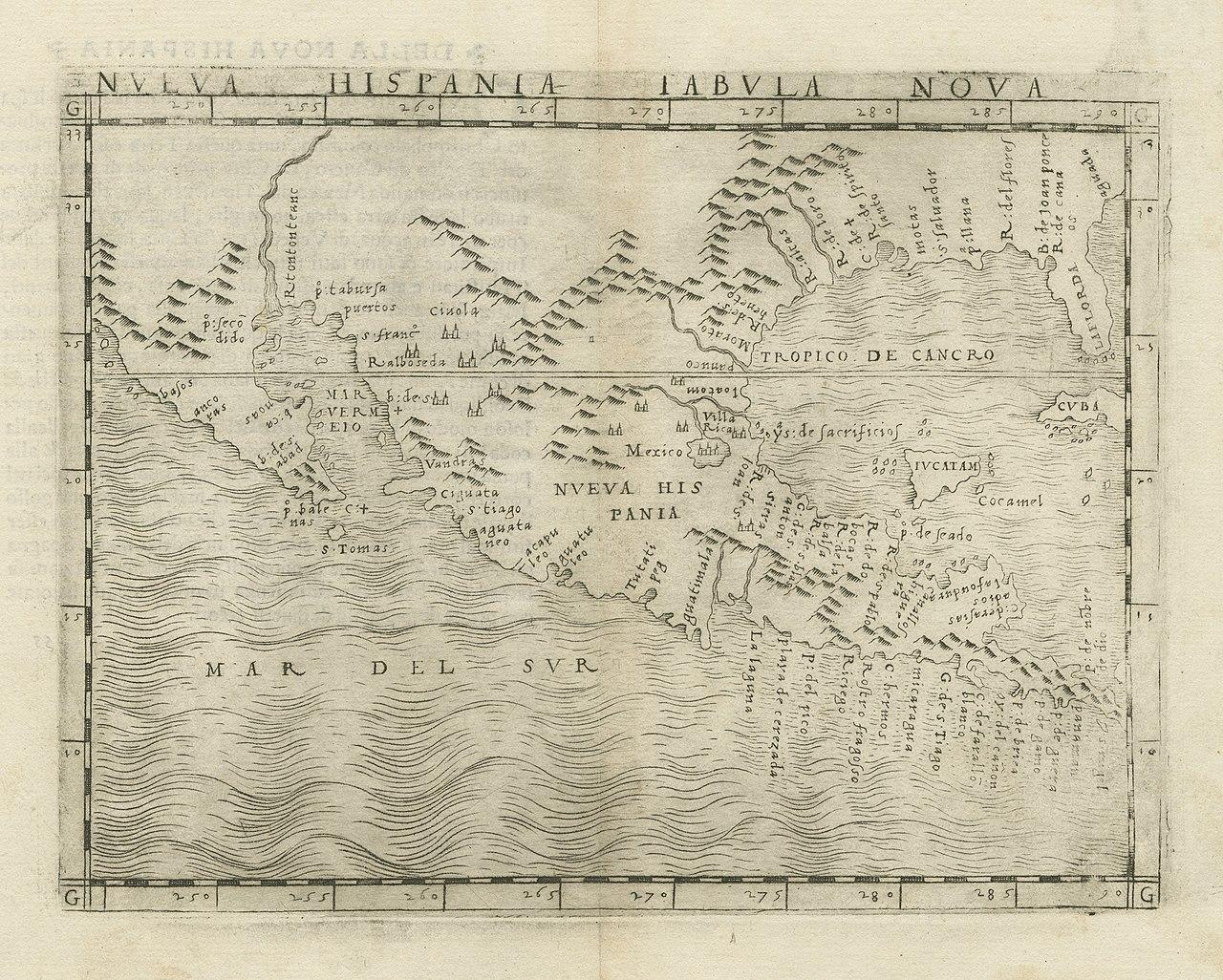

Top map: Giacomo Gastaldi's 1548 map of New Spain, Nueva Hispania Tabula Nova.