Photo: The dance team of the National Indigenous Disabled Women Association Nepal embodies disability pride and joy. ALT Text: Six women in wheelchairs wearing bright pink tops and yellow garlands join hands in Nepal.

By Rucha Chitnis, Communications Director, Disability Rights Fund

In recent years, Indigenous-led philanthropy has made a powerful case for decolonizing wealth. As Melissa Nelson (Anishinaabe/Métis and a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians), President of the Cultural Conservancy, a scholar and ecologist, reminds us, much of the financial wealth of philanthropic dollars comes from Indigenous lands, resources, and labor that was extracted in harmful ways. “Reimagining wealth is also a form of restitution and healing that is needed in our world today,” she said. At the Disability Rights Fund (DRF), while we appreciate the growing dialogues around equity in philanthropy, the actual practice leaves a lot to be desired.

Here’s why: Since 2008, DRF has supported the disability rights movement around the world by resourcing organizations of persons with disabilities (OPDs) to advocate for equal rights and full participation in society. While philanthropy is abuzz with conversations on intersectionality, less than 2% of global human rights funding goes to persons with disabilities. This is an outrage, because one billion people around the world experience some form of a disability, with nearly 28 million Indigenous women living with a disability. And yet, we also know that it is rare for Indigenous persons with disabilities to have a seat at the table when funding decisions are made. Participatory grantmaking is a core part of our practice, along with a gender-transformative approach. Often, we are the first and only funder of women with disabilities and groups belonging to marginalized identities, including Indigenous Peoples. This must change.

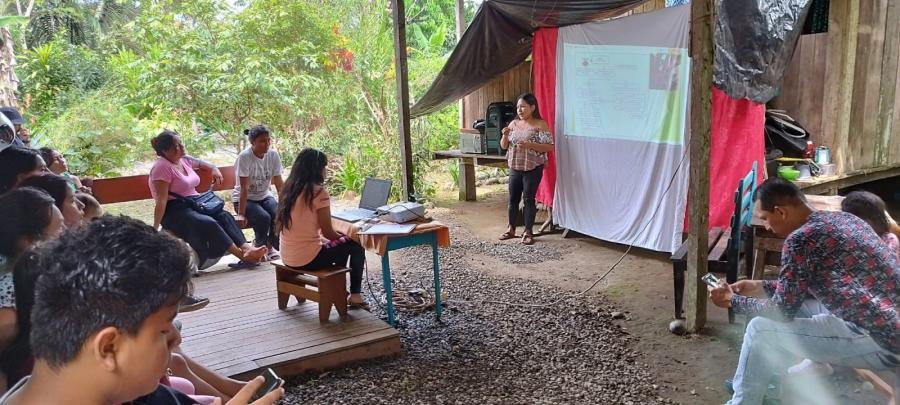

Photo: The team of the Association of Indonesian Women with Disabilities (HWDI) advocates for the rights of Indigenous women with disabilities in South Sulawesi.

As a learning organization, we are eager to share the many lessons we glean in community with grantees. Here are four tips for funders to be inclusive of Indigenous persons with disabilities and their vibrant movements:

- Recognize the historical context of colonialism and a long legacy of resistance: Many of our Indigenous grantees belong to communities that have resisted colonialism and also forced assimilation from modern nation states. The Batwa people are among the most marginalized in East Africa. “Working with the government is a challenge for us because of their policies to abolish ethnic identities. They have not even acknowledged the historical injustices,” shared one Batwa activist confidentially. For Batwa Peoples, political representation is critical for the recognition of their rights. “We need land, political representation, and freedom!” they summed up. We know that Batwa persons with disabilities are excluded from government programs if they claim their indigeneity. This forced assimilation, while they face intersecting oppressions, is a continuation of a long process of dehumanization and exclusion. DRF’s support for the First People Disability Organization supports Batwa parents of children with disabilities to build their capacities to advocate effectively for the rights of their children in the context of emergencies. In the face of it all, Indigenous movements are holding both philanthropy and governments accountable for inclusion. Funders must resource the self-determination of and rights-based advocacy led by Indigenous Peoples and also educate themselves on how systems created by colonization perpetuate in philanthropy.

- Center Cultural Competency: One of DRF’s key strategies includes resourcing technical assistance to equip our grantees to advocate on the rights and inclusion of persons with disabilities. This includes increasing our grantees’ technical knowledge about the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (CRPD) and its implementation. During COVID-19, many of our grantees in the Pacific Islands were in a restrictive lockdown with travel moratoriums in place. To connect our grantees during this uncertain time, DRF started a series of conversations called Talanoa with OPDs. Talanoa is a powerful Indigenous framework in Fiji and across the Pacific for an inclusive and participatory conversation. These dialogues create a safe space to share stories and build empathy through deep listening and moving toward collective solutions. Through these dialogues, DRF grantee Women with Disabilities Association in Papua New Guinea facilitated a Talanoa on the connections between gender equality, disability rights and inclusion. This was followed by another grantee, the Disability Pride Hub, exploring a conversation on gender and SOGIESC (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression and Sexual Characteristics) diversity. Through these dialogues, our grantees learned about each other’s advocacy and strategies, opening doors for cross-regional collaborations.

- Resource Inclusive Storytelling: Ableism is deeply entrenched in the dominant narrative, which is exclusionary and dehumanizing. Storytelling about persons with disabilities is often paternalistic and harmful, perpetuating dangerous stereotypes. Think inspiration exploitation, a definite no-no. Changing this ableist narrative is essential in philanthropy, too. DRF’s strategic partnership with the Disability Justice Project (DJP) has resourced Indigenous storytellers with disabilities to frame their own agenda and solutions. Because #NothingAboutUsWithoutUs is also about flipping the script of ableism! DJP Fellow, Dija, is an Indigenous activist and chairperson of the Association of Indonesian Women with Disabilities, a DRF grantee. Dija collects data on Indigenous persons with disabilities in the village of Batubassi in South Sulawesi and also assists on cases of gender-based violence against women with disabilities. Through the DJP fellowship, Dija learned about the tools for inclusive and accessible filmmaking. “I am a storyteller to inspire my community, the Indigenous community, and especially [for] Indigenous women with disabilities to feel empowered,” she said. For her DJP project, Dija produced a film called, Not to be Feared, documenting the stigma experienced by people with leprosy.

- Be Nimble and Pivot: Around the world, COVID-19 has had a disproportionate impact on persons with disabilities, creating crises of livelihoods, safety and health. As our team learned about the lived experiences of our grantees during a public health emergency, we pivoted nearly 80% of our grants to respond to the ground realities and trust the shifting strategies and priorities of grantees. Funders must be nimble. Restrictive grants with complex reporting mechanisms are onerous for grassroots Indigenous groups that are facing very real security and safety risks during these times of political and economic uncertainty.

Lastly, funders in the Global North must cultivate a culture of humility and be open to learning, unlearning, and evolving. Funder affinity networks, like the International Funders for Indigenous Peoples, and advocacy groups, like the Cultural Survival, are incredible resources for cultivating a practice of intersectionality.

It’s time for philanthropy to act. Because practice makes a foundation inclusive.