By Terri Hansen and Joe Yracheta

This is turning out to be a particularly nasty flu season and is especially concerning for Indigenous children and adults migrating from Latin, Central, and South America detained in holding pens at the U.S. southern border, and then denied flu vaccination.

Some genetics experts say Indigenous Peoples run a greater risk of dying from flu-related illness than other or ethnic groups, especially from the still-circulating H1N1 influenza A strain.

According to Freedom for Immigrants, most migrant detainees are from Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala and have more Indigenous ancestry than other Hispanic groups, according to the American Journal of Human Genetics, as reported by journalist James Giago Davies.

Research dating from the 2009 H1N1 influenza A pandemic found Indigenous Peoples suffered flu-related deaths at rates up to eight times greater than other races or ethnicities.

The scientific journal, Clinical Infectious Diseases, stated the death rates in Mexico from reported 2009 H1N1 influenza cases were the highest of any other country for which estimates were available. In that country, individuals aged 5–19 and 20–59 years were at disproportionate risk of death.

In the United States, those who identify as "Hispanic/Latinos" comprised 15 percent of the population yet represented 30 percent of all reported cases during the early spring 2009 wave of the epidemic. H1N1 infection in 2009 put 89 out of every 100,000 "Hispanic/Latino" children under the age of five in the hospital for flu-related illness, compared to 29.1 out of every 100,000 of non-Hispanic white children of the same age.

A U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study of American Indians in 12 states including Arizona and New Mexico found their death rate from H1N1-related illness was four times greater than other races or ethnicities.

John Redd MD, an epidemiologist with the Indian Health Service in 2009 and a report co-author, told this reporter that year they had been worried at the outset of the H1N1 outbreak. “We knew from previous outbreaks that there was severe disease happening in American Indian and Alaska Native and other Indigenous populations.”

And a 2014 study published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found that influenza-related hospitalization rates suggest that American Indians and Alaska Natives might suffer disproportionately from influenza illness compared with the general U.S. population.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that everyone six months and older get a yearly seasonal flu vaccine by the end of October, if possible, to ensure the best available protection against the flu. But children in migrant detention will not be vaccinated.

“In general, due to the short term nature of Customs and Border Protection [CBP] holding, the time the vaccine takes to begin working, and the complexities of operating vaccination programs, neither CBP nor its medical contractors administer vaccines to those in our custody,” CBP told CNBC on August 20.

But the denial of flu vaccine to migrant children upon arrival to this country is especially concerning due to the lack of continuous care and barriers these children face in obtaining adequate, ongoing treatment once they are released into the U.S., health care providers in the U.S. say.

President Trump's new policy of returning migrants to be held in Mexico means thousands of unvaccinated people will be crowded together in unhealthy border camps.

Three migrant children have died of flu-related infections in the past year while in CBP detention, including a 2 year-old, a 6 year-old, and 16-year-old Guatemalan Carlos Gregorio Hernandez Vasquez, who died in a concrete cell block after writhing and vomiting on the floor alone overnight last May, according to video obtained by ProPublica.

A team of Harvard and Johns Hopkins medical experts say these tragic deaths reflect a rate of influenza death substantially higher than that in the general population. They called for an investigation into these deaths in a letter to Congress. The letter also argued that CBP should vaccinate the children to prevent more deaths.

“Data from several countries indicate Indigenous populations suffer from more severe influenza," Andrew Pekosz, Professor of Microbiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health told Cultural Survival in an email. "The reasons for this aren’t clear, but it does make these populations high priority for influenza vaccination."

Historical evidence indicates Indigenous populations have been disproportionately affected by influenza pandemics than other population groups since record keeping began. These numbers are significant.

Studies in 2009 found that deaths related to the H1N1 flu in Indigenous populations in Canada, New Zealand and Australia were three to eight times higher than other races and ethnicities.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people get influenza more often, and get more severe forms of influenza, than non-Indigenous people.

And studies of Indigenous populations in Alaska and Australia by researchers at Australia’s University of Melbourne in 2013 found that genetic differences put Indigenous Peoples at higher risk of severe complications and death from a strain of Avian influenza or bird flu called H7N9 that had emerged in China and Taiwan.

To protect Indigenous Australians, the Australian researchers studied 31 populations from different continents based on 1919 data from the influenza pandemic that had decimated Indigenous Peoples worldwide, study co-author Katherine Kedzierska, associate professor at the University of Melbourne’s department of microbiology and immunology told this journalist in 2014.

The researchers tested pre-existing immunity and found the prevalence of T-cell immunity depends on ethnicity and that Indigenous Peoples, owing to their historical isolation, lacked a key protein necessary to fight the virus.

The researchers found that just 16 percent of the Indigenous populations in Alaska and Australia had a robust T-cell response, compared to 57 percent of non-Native populations.

--Terri Hansen is a climate and science journalist, and a member of the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska. Follow her on Twitter @TerriHansen. Joe Yracheta is a health disparities scientist of MexIndigenous American heritage. Find him on Twitter @YrachetaJM.

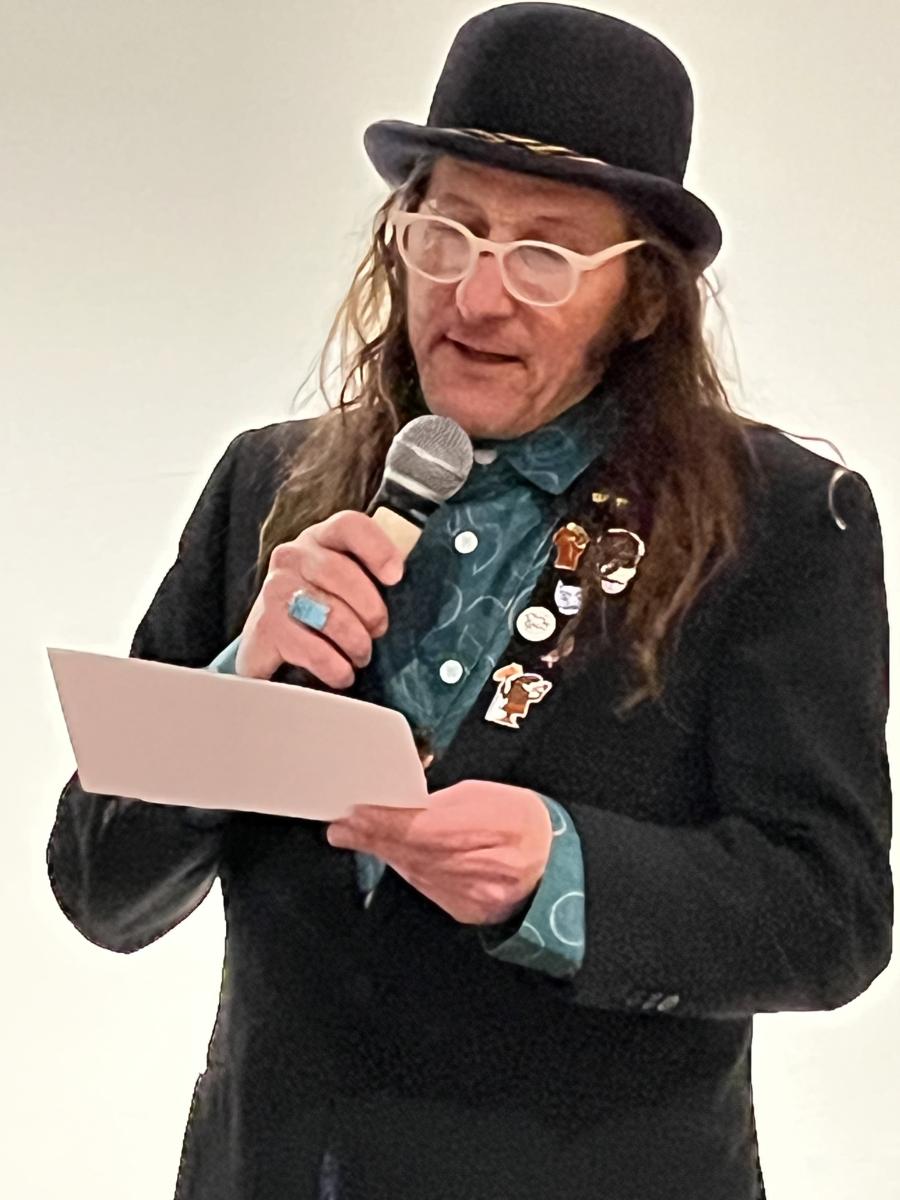

Photo: Charles Edward Miller.