The Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, better known as the Escazú Agreement (named after the city in Costa Rica where it was adopted), is the first binding regional environmental agreement. It was adopted on March 4, 2018, after four years of negotiations, and has been signed by 24 countries and ratified by 15. The most recent country to do so was Granada, which ratified the Escazú Agreement on March 20, 2023. Brazil, Paraguay, Peru, and Guatemala have not yet ratified it, meaning it is not binding for these States. Venezuela, Honduras, and Cuba have not signed it.

The Escazú Agreement came as a result of the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, whose Principle 10 states: “Environmental issues are best handled with the participation of all concerned citizens, at the relevant level. At the national level, each individual shall have appropriate access to information concerning the environment that is held by public authorities, including information on hazardous materials and activities in their communities, and the opportunity to participate in decision-making processes. States shall facilitate and encourage public awareness and participation by making information widely available. Effective access to judicial and administrative proceedings, including redress and remedy, shall be provided.”

In 2012, Latin American and Caribbean countries signed the Declaration on the Application of Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration, which laid the foundation for the Escazú Agreement. An important concept that appeared in ensuing discussions on the application of Principle 10 was access rights. These were divided into three categories: the right to access environmental information, the right to access environmental participation (i.e., decision-making processes), and the right to access environmental justice.

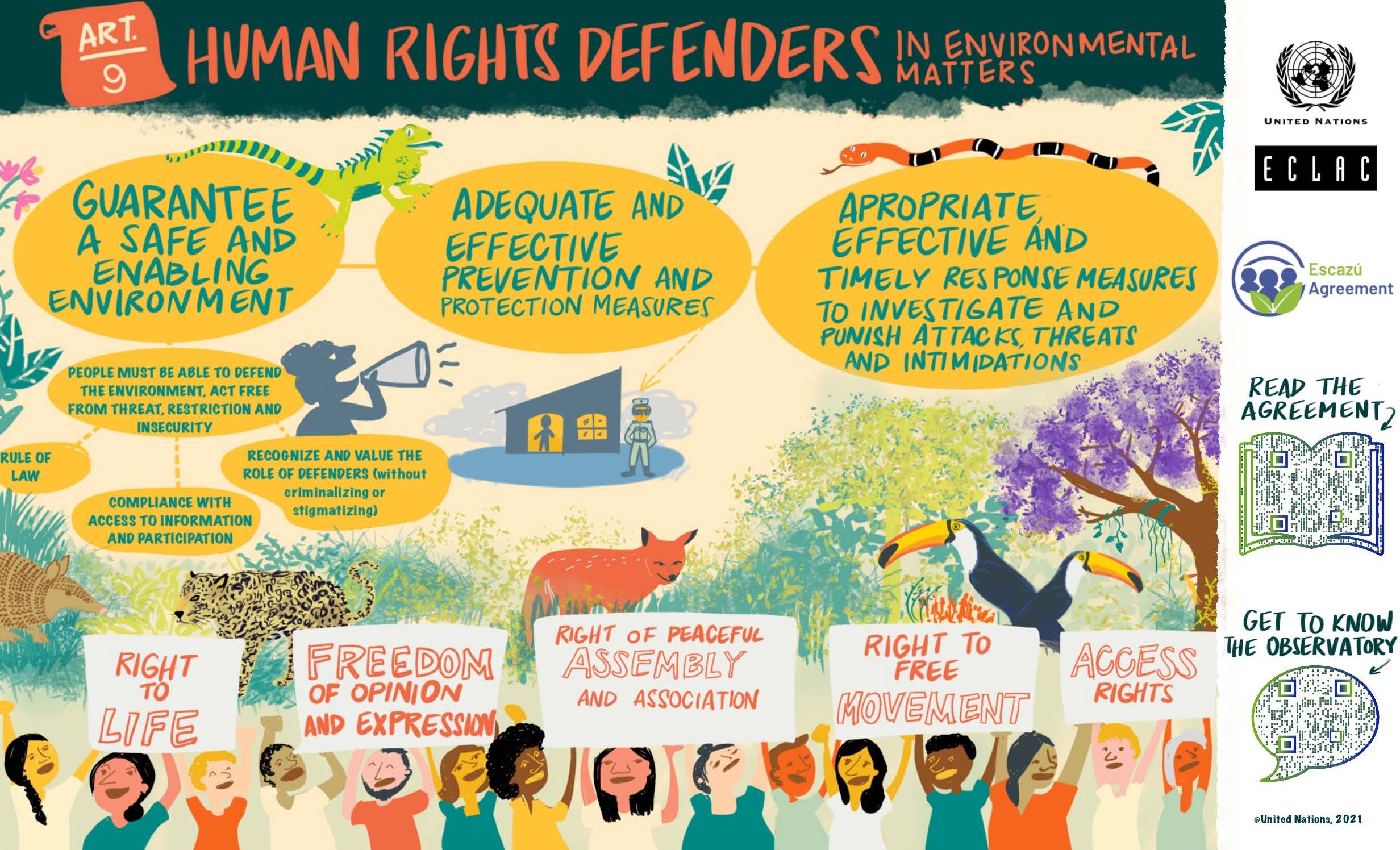

The Escazú Agreement is the first binding treaty to contain specific provisions on environmental defenders. It is of special relevance that its geographic scope encompasses one of the most dangerous regions to be a human rights defender, as three out of four assassinations of environmental defenders take place in Latin America. The agreement obliges States to take effective measures to recognize, protect, and promote all the rights of human rights defenders in environmental matters and to investigate and punish attacks, threats, or intimidation against them.

How Could the Escazú Agreement Benefit Indigenous Peoples?

Indigenous Peoples are innately environmental rights defenders. When they protect their lands, they are protecting the environment. It is not a coincidence that 80 percent of the globe’s remaining biodiversity is within Indigenous territories; Indigenous Peoples live in profound and reciprocal relationships with their lands and are best equipped to continue protecting them.

In terms of the right to access environmental information, the Escazú Agreement mentions in Article 5.4 that States have the obligation to facilitate access to environmental information and specifies that Indigenous Peoples have the right to receive assistance in preparing their requests and to obtain a response. This right could serve as a standard for establishing procedures to access information in a timely manner.

According to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and International Labour Organization Convention 169, Indigenous Peoples have the right to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent. This means they have the right to give or withhold consent prior to the implementation of projects that will impact them. Development companies often fail to meet their obligation to provide Indigenous communities with transparent and trustworthy environmental impact information prior to development projects. Companies tend to take advantage of this, tearing apart the social fabric of communities by sowing division. This sometimes results in part of the community agreeing—but not giving consent as established by international standards— to harmful projects, finding out the real environmental consequences only after a project has commenced, a point at which it is very difficult to stop it. This lack of access to appropriate and timely information violates Indigenous Peoples’ right to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent. The Escazú Agreement requires States to promote public access to information held by private companies.

Article 6.3 establishes that States must share environmental information systems offering a variety of materials including “information on Environmental Impact Assessment processes and on other environmental management instruments, where applicable, and environmental licenses or permits granted by the public authorities.” Environmental Impact Assessments are crucial in order to estimate the potential impacts and risks a new project could have on Indigenous land and people. Facilitating access to these analyses could help establish better practices for FPIC processes and, as a consequence, safeguard Indigenous rights. Article 6.6 also references the obligation of authorities to share the relevant environmental information in the various languages used in the country and in formats that are comprehensible to groups in vulnerable situations. This would mean disseminating the materials in Indigenous languages and through culturally appropriate channels of communication.

The right to access public participation in the environmental decision-making process is described in Article 7. Its provisions protect the right of the public to participate in decision-making processes, revisions, re-examinations, or updates regarding environmental permits, land-use planning, policies, and others from early stages and in a clear, timely, and comprehensive manner, including customary methods. The Escazú Agreement also includes a list of information that should be made public in the decision-making process that could clarify responsible entities or companies, and as such facilitate the identification of wrongdoers.

These provisions may contribute to practices that may align with Indigenous Peoples’ right to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent, in the sense that they may fortify practices of participatory decision-making. However, it is important to distinguish between the individual right of every citizen to participate in decision-making processes–as established by this accord–from the collective right to give or withhold consent that Indigenous Peoples in particular have according to international standards.

In regards to the right to access justice in environmental matters, established in Article 8, the Escazú Agreement states that people have the right to go to court if the environmental information they requested was not provided, if they were denied participation in decision-making processes, or when there is a risk of a project negatively affecting the environment. In the case of Indigenous Peoples, access to remedy for negative environmental impacts that affect them or restitution for land dispossession has often been unavailable, in spite of their right to remedy under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Sometimes Indigenous Peoples are, at best, awarded monetary compensation. In many cases this is inadequate; land is much more than a material resource for Indigenous Peoples, and the loss experienced by destruction of or forced removal from land has impacts on cultures and collective histories that cannot be resolved monetarily.

Many of the Escazú Agreement’s decision-making provisions may offer opportunities to establish practical steps for accessing information and participation, but would still not fully implement Indigenous rights, as participation is limited to consultation of the public and does not require consent—a crucial difference from the rights protected in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and International Labor Organization Convention 169. Another significant matter to take into consideration are the collective rights of Indigenous Peoples; the text references “the public” or “persons or groups in vulnerable situations” as recipients of these rights but does not specify Indigenous Peoples, which could limit the scope of its application. The Escazú Agreement sets positive minimum standards in order to protect Indigenous environmental defenders, but when applied to Indigenous Peoples it also needs to be interpreted in alignment with the specific rights Indigenous Peoples hold. As the agreement mentions, States should make sure domestic and international obligations in relation to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities are observed in the implementation of the agreement. Cultural Survival believes the combination of these two different entities—Indigenous Peoples and local communities—disregards the collective rights to which Indigenous Peoples are entitled as distinct, self-determining Peoples.

Latest Updates and Implementation Process

The first meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP1) for the Escazú Agreement took place in Santiago de Chile from April 20-22, 2022. Several decisions were made in this first conference, including setting the rules for the election of the Committee to Support Implementation and Compliance, which is a subsidiary body of the Conference of the Parties to promote the implementation of the Agreement. The seven experts composing this body will be elected during COP2. During COP1, it was also decided that an ad hoc working group on human rights defenders in environmental matters would be established. This is an opportunity for public participation, including for Indigenous Peoples, at the annual forum on Human Rights Defenders in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean. The working group was charged with the responsibility of creating an action plan for protection of environmental defenders. On November 22-23, 2022, the First Annual Forum on Environmental Human Rights Defenders from Latin America and the Caribbean took place in Quito, Ecuador, with the goal of developing this action plan.

The UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean has released an implementation guide for the Escazú Agreement. However, the implementation process has varied widely among signatories. Argentina launched a public consultation on the implementation of the agreement that asked for the participation of civil society in several aspects. Many interviews were conducted, although some representatives of civil society and organizations say they are not satisfied with the result, as environmental defenders are barely mentioned.

Bolivia’s role in COP1 surprised many as it fiercely fought the articles promoting a far-reaching participation of civil society in the conferences and presented a counter proposal that excludes Indigenous Peoples. In México, where more than 500 environmental conflicts have been identified, the Escazú Agreement was ratified in 2020 and was used in court rulings even before it was ratified by the government. And in Uruguay, which was one of the first countries to ratify the agreement, some organizations are reporting that obtaining access to environmental information is still complicated and that it is not available throughout the whole country.

COP2 will take place April 19-21, 2023, in Buenos Aires, at which time members of the Committee to Support Implementation and Compliance will be elected. This event represents yet another critical opportunity to advocate for the effective implementation of the Escazú Agreement, the proper inclusion of public policies on environmental rights defenders at the national level, the consideration of Indigenous Peoples rights in the implementation of the agreement, and the ratification of countries that have not yet done so.

Main image courtesy of ECLAC.