On May 10, 2016, the Library of Congress featured Native American writers on a panel, "Spotlight on Native Writers." Eric Gansworth, Linda LeGarde Grover, and Stephen Graham Jones read excerpts from their work and Deborah Miranda moderated the discussion and Q&A.

Shortly after "Spotlight" the writers and audience walked a few blocks to the Folger Shakespeare Theater for a reading and discussion by Louise Erdrich, the 2015 Library of Congress Prize in American Fiction winner who read from her new novel La Rose and participated in a discussion Q&A moderated by Professor Howard Norman of the University of Maryland.

Cultural Survival Contributing Arts Editor Phoebe Farris interviewed some of the writers.

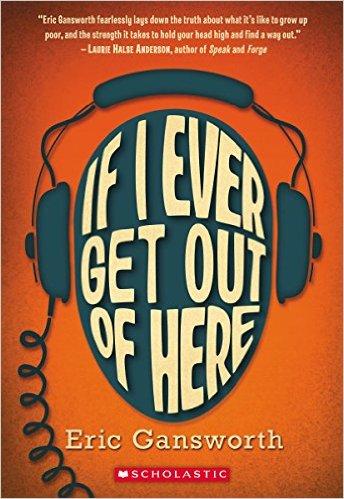

Eric Gansworth (Onandaga Nation), is an enrolled Onandaga tribal member living on the Tuscarora Nation Territories in upstate New York. He is a professor of English and Lowery Writer-in-Residence at Canisus College in Buffalo, New York. Gansworth will be the NEH Visiting Professor of Native American Studies at Colgate University in fall 2016. A visual artist and writer, Gansworth is the author of the If I Ever Get out of Here, Extra Indians which won the American Book Award, Mending Skins which won the PEN Oakland -Josephine Miles Award, Smoke Dancing, Indian Summers, Nickel Eclipse: Iroquois Moon, and a memoir, Breathing the Monster Alive.

Phoebe Farris: Why did you decide to write a young adult novel and what ages encompass that category? Do you think young adults can also relate to your other books?

Eric Gansworth: It was actually an opportunity that arose. I've written about young life for most of my career, but always from the vantage point of an adult looking back. The American Indian Children's Literature activist, Debbie Reese, and I became friends a number of years ago, after we'd been speakers at the same conference. Debbie asked me if I'd ever consider writing for young people. At the time, I didn't think writing for young people would be that different, as I read general audience novels when I was in junior high and high school. My young adult editor, Cheryl Klein, contacted Debbie, seeking Indigenous writers. Debbie then put us in contact and after some discussion, the right story eventually emerged. I think if a young adult is attracted to my work for younger readers, they might engage with my other novels, though they might find them more slowly paced. I tend to write pretty contemplative fiction. That's true for my young adult work too, but maybe more so for my other work.

PF: Do your novels dictate your visual imagery or do you begin a drawing first and develop the story later?

EG: Though each project has been a little different in the organic growth stage, I do tend to think about my work visually and verbally at the same time. Sometimes an element of the story shapes the direction the paintings take and sometimes a series of paintings I've been working on get me thinking about narrative. They're on the balanced side. The stories are not narratives of the paintings, and the paintings are not illustrations of events in the work. They are more like siblings, I suppose.

PF: As a man immersed in Tuscarora and Onondaga culture how do you view the female role in Iroquois societies? Do you think their political and spiritual power helps you develop female characters in your writing?

EG: I'm not sure I would categorize the influence as either political or spiritual, as my work doesn't tend to lean overtly into either of those directions very often. That said, I suspect that because of that long, rich cultural presence, most of the women I've known from the communities have been very strong in expressing themselves as major figures in the culture. That has been so true, actually, that as a young person, I found all the talk about the emergence of feminism quite puzzling. In my experience in our communities, that dynamic had always been true. Most of the influential adults I knew growing up were women, so I took gender equity as a given. It was only later, as an adult in the broader world, that I started to see that divide. Because of my history, the women in my fiction tend to be among the most strong-willed and active characters, but I never thought of that as radical. It's just me reflecting the world I knew.

PF: Out of all the books you have written do you have a favorite?

EG: I am not sure I do. You live with the composition and editing process for so long, there are times when you are very happy with the work and times when you never want to see it again. One of my books about which I had the most doubt seems to be one that gets taught a lot and I have no idea why that one, more than the others, is successful in the classroom.

It took many attempts, and as such, many failures, to finally write the story that became IF I EVER GET OUT OF HERE. I had tried to write versions of that story for over a decade, so it was a relief to finally be done with it, to find the most meaningful structure for it. That may suggest it's my favorite as I usually abandon an idea long before ten years of living with it have gone by. But I might feel different a couple years from now.

PF: How do you feel about the fact that white writers in the USA are just identified as American writers but writers of color are identified as Indian writers, Latino writers, Asian American, African American writers etc.? Do you think having our race or ethnicity attached to our names is a strength or weakness as far as reaching audiences? Have you ever wanted to be recognized as just a writer rather than a Native American writer?

That's an interesting question. I know that I choose to write about a very, very small demographic, and I've worked in a professional world that is not reservation based for long enough that I could easily write about situations that don't concern the reservation where I grew up. But it's still a universe of fascination to me. I don't see that I'll grow tired of it, and I see that as a choice I'm making. I suppose I see the label as an analogue to the way, just to name a similarly sized group, Appalachian writers get labeled as such because they're writing about a very small subculture as well, the label American Indian writers seems informative to me.

However, certainly as Louise Erdrich noted in her Folger Library presentation, one drawback of such an explicit label is that a lot people, perhaps shaped by publishing demographics, see a couple of names they're familiar with as "THE Native American Writers." As such, they seem to feel reading one or two is enough, that all of our stories must be similar to those few names they know, and thus not necessary.

It may do a disservice to the voices of individual Indigenous writers. I don't really see that happening in the world of white writers. Perhaps it does and I'm just not aware of it. But do all white male writers get chronically compared to Rick Moody or Cormac McCarthy? I'm thinking they don't. It doesn't seem like people say, "Oh, I've read Tobias Wolff, I don't need to read another white guy because their stories are going to all be similar." That IS the sort of way many Indigenous writers are categorized and/or are dismissed as redundant in readers' choices.

PF: Cultural Survival Quarterly is read by Indigenous people around the world. Is there anything you would like to say to aspiring Indigenous writers in the USA and other countries?

EG: I would say that the hardest thing for me to learn was to trust that my story and the stories of contemporary Indigenous people could be interesting to others. When I was a young, developing writer, in high school, I felt like my stories had to be about some other life. I didn't start writing about the world I knew until I was maybe 20. That seems young, of course, but I'd been writing for seven years by then. That's a long time to recognize the value of your own experience. So what I would say to any aspiring writer is to read what others have done before you and learn your craft. Specifically to aspiring Indigenous writers, on top of that, because craft is your biggest tool, is to trust that your story is valuable. The better you get at the craft end, the better you'll be able to express that story, and reach an audience with the richness of your experience.