Interviews by Miriam Anne Frank, article by Miriam Anne Frank and Alexandra Carraher-King

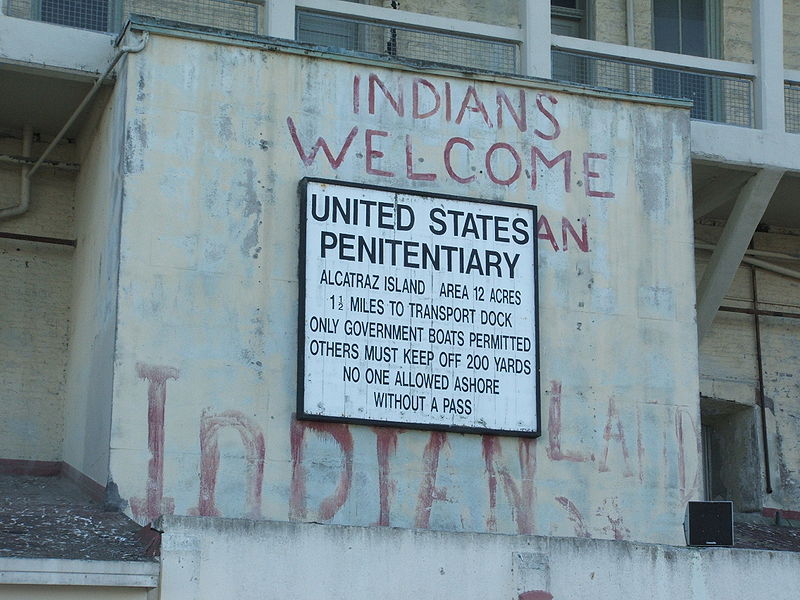

It is an ever present paradox that when you enter into the San Francisco Bay in California, under the Golden Gate Bridge - which for so many is a symbol of hope and freedom - your gaze falls on the infamous Alcatraz Island. Although it boasted the first lighthouse on the West Coast is it primarily known by most as a notorious prison, once containing Al Capone, one of the most feared criminals of his day. What is hardly known is that the some of first prisoners were California Indians resisting incursions of settlers and miners during the Gold Rush. Another group of Indigenous prisoners, 19 Hopis were later also held there for resisting the removal of their children to U.S. Boarding Schools.

When Alcatraz became financially untenable as a prison the site was closed and abandoned until the Native American occupation of this site began on November 20, 1969. Eighty-nine Native Americans led the occupation which, at its height, swelled to a total of 400 Natives and allies. During this time Bay Area supporters, including the Black Panthers, organized boats to deliver food and other essential supplies to the movement.

Known as Indians of All Tribes, they rooted this action on the fact that the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868)betweenFinal the U.S. and the Lakota Peoples, outlined that all such retired, abandoned or otherwise unutilized federal land should be returned to the Native people who once occupied it. The choice of Alcatraz is rife with symbolism, mirroring many Indian reservations, a place with harsh living conditions, land unsuitable for sustainable living and lack of economic possibilities.

The occupation held out for 19 months, ending with a forcible intervention by the U.S. government. While the physical occupation ended it sparked and ignited a movement. Although these activists did not know it at the time, Alcatraz marked a turning point in the national dialogue surrounding Native American rights. One can trace its lasting impact to Standing Rock, which has been referred to by some as “the Alcatraz of our day”. It can be seen as one of the roots upon which basis the growing global Indigenous Peoples’ movement came together to collectively work towards achieving the historic adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

On October 14, 2019, on Indigenous Peoples’ Day - marking 50 years since that occupation - Native Americans, including some of the original activists, joined by Native Hawai’ians, Native Alaskans, and Indigenous Peoples representing many parts of the globe, along with supporters, joined a pre-dawn trip to Alcatraz where in a sunrise ceremony they commemorated and honored the sacrifices made.

By the time daylight came the island was circled by Indigenous canoes. They had taken this journey to celebrate the history of Indigenous Peoples’ resistance to colonialism, but also reminding the nation of how much still needs to be done to make up for the past atrocities. The canoe journey that culminated at Alcatraz was years in the making, said Julian Brave Noisecat (Canin Lake Band Tsq'escen), one of the leaders of the commemoration, “Two years ago my father and I had just returned from the Tribal canoe journey up to Campbell River British Columbia and we were hanging out with our good friend, Eloy Martinez, who was one of the participants in the occupation, and someone who has played a huge role in maintaining the legacy of the occupation both on the island and in the community.” Together, they “came up with the crazy idea that [they] would organize a canoe journey for the upcoming fiftieth anniversary.” The idea was not so crazy, though, once Noisecat’s volunteer committee set to work: the team “met every week and ended up making the thing [the commemoration] happen.”

“We got over we got 18 canoes representing dozens of Tribes, between 500 and a thousand people throughout the day, and over 20 press hits including all the local TV stations a bunch of national print publications, and the New York Times is actually going to publish a story very soon, so it is a very successful gathering and journey,” Noisecat recalled.

The journey achieved its aim of continuing national dialogue surrounding Indigenous rights: only eight days later, the New York Times indeed published a piece titled “Occupy Alcatraz: Native American Activism in the Modern Era” in addition to releasing a lesson plan on teaching Native American activism. Dozens of other outlets have reported not only on the commemoration but also on the history of Indigenous protest in the nation. Noisecat described the experience of planning the event and seeing its success as “powerful.”

To quote the International Indian Treaty Council Executive Director, Andrea Carmen (Yaqui), the commemoration celebration marks a large achievement in the work of Indigenous rights, as the occupation was “something that began the international Indigenous movement, here in Alcatraz...and continues to inspire it...We've been doing protests to commemorate the occupation, but also to challenge the myth of Columbus and the continuing impacts of the Doctrine of Discovery that he utilized to pillage Indigenous Peoples and the land on this continent, because we well know that he didn't discover anything. He was a lost colonial pirate looking for Hindustan. It wasn’t called India at the time. And we know from his diary what his view of the Taino people that encountered him and his lost starving scurvy-ridden sailors. He said in his own diary that the [Taino] people are so beautiful and so generous they would give [Columbus] anything they had. He went on to write, ‘With 50 men we could enslave them completely. ’So rather than appreciating what he'd found in the treatment of men, the food, the generosity he encountered, and the beauty…[he thought of] enslavement and...ornaments that were worn by the Taino people…[which were taken and] melted down by the Vatican... many, many centuries ago. It was important for us to stand for truth in history as well as to commemorate the occupation of Alcatraz, which sparked the national and the international Indigenous movement.”

The commemoration on October 14, 2019 symbolizes the continuing fight for Indigenous Peoples’ rights that has been kept aflame for centuries. In the words of Tony Gonzales (Seri/Chicano), Director American Indian Movement-West (www.aim-west.org), “We all come to Alcatraz Island to commemorate and acknowledge 527 years of Indigenous Peoples’ resistance to colonization throughout the Americas and I think what we witnessed today [at the commemoration] is work that was begun by many men and women before us.”

One of these people was Carmen herself, who participated in the occupation when she was only 17 years old: “Richard Oakes...another student from San Francisco State came down to meet with our little Native American Student Association from the University of California at Santa Barbara, and explained to us what they were going to do and that they wanted us to be part of it. We sent our chairman up, and I was vice chair—I was a 17 year-old college freshman. I was in charge of collecting canned goods and blankets and signatures so they wouldn't go in and shoot them all. I didn't get much money but mostly goods and support. I can just speak for myself and how inspired I was by the reasons given [for the occupation]... the broken treaties, the forced relocation that brought thousands of Indigenous Peoples under force to the Bay Area and other cities off the reservations. The San Francisco Bay Area became the third largest urban indian population in the United States as a result. We owe a lot to those students, young people, that stood up,” Carmen explained. “I think it's important for us to remember it was students and young people that conceived of and led the occupation even though many others came to join them.” The 1969 occupation of Alcatraz as a decisive moment in the history of Indigenous rights both in the United States and globally. Not only did the occupation mark a continuation of resistance against colonization, it furthered future actions of resistance, including the occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973 and the more recent occupation of the Dakota Access Pipeline Occupation in 2016. “I really see a direct link from the occupation in 1969 to the adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007. There's a direct link and chain and history there,” stated Carmen.

This legacy of the occupation of Alcatraz exists not only in the collective resistance of Indigenous Peoples against the United States’ policies of persecution and assimilation, but also in their individual stories and experiences. Noisecat did not participate himself in the 1969 occupation, but the impact the event had on his understanding of his history as a Native American was profound. He grew up in Oakland. “I remember going to the sunrise ceremonies from the time when I was five years old. Alcatraz was a huge part of the community's history for me. There was a huge sort of legacy of the occupation in the community and obviously a lot of people who themselves participated or whose parents or aunties and uncles participated. It was just always a huge part of my upbringing, that sort of awareness of that history.”

Thorne Lapointe (Sicangu Lakota) who participated in the canoe journey, also felt a strong connection to Alcatraz despite being born well after the occupation. “We travelled here from Minnesota. We’re seeing where our father and where our predecessors overtook Alcatraz, fighting for their rights. We went out this morning to actually step into a place where we heard all these stories come out from one of the central and pivotal moments in the history of Indigenous Peoples, and really, a springboard launching for our rights movements that began during the more recent times. That was pretty historical morning to have those canoes going around Alcatraz Island.”

The awareness that the commemoration raised was crucial. “The thing that was always notable to me,” Noisecat recounted, “was that the history of occupation was not well-known among non-Native people. While this thing that happened on Alcatraz was a huge part of my understanding of the history of my community and the place where I lived, other people didn't even know that it had happened.”

Carmen had a similar experience with others’ lack of knowledge on Indigenous Peoples’ rights, especially abroad. “Having had the chance to be at the United Nations in Geneva, Switzerland, and many other European countries. I hear from a lot of the people there that this is the first time, [due to] the lack of publicity around [the] Alcatraz occupation and then around the Wounded Knee occupation in ‘73, that they realized that there were still American Indians living, that we weren't completely extinct. Not only that, we're organizing and standing up and calling for rights and treaties and protecting the environment, our cultures, and languages—all of those things that we continue to work on today,” she recalled.

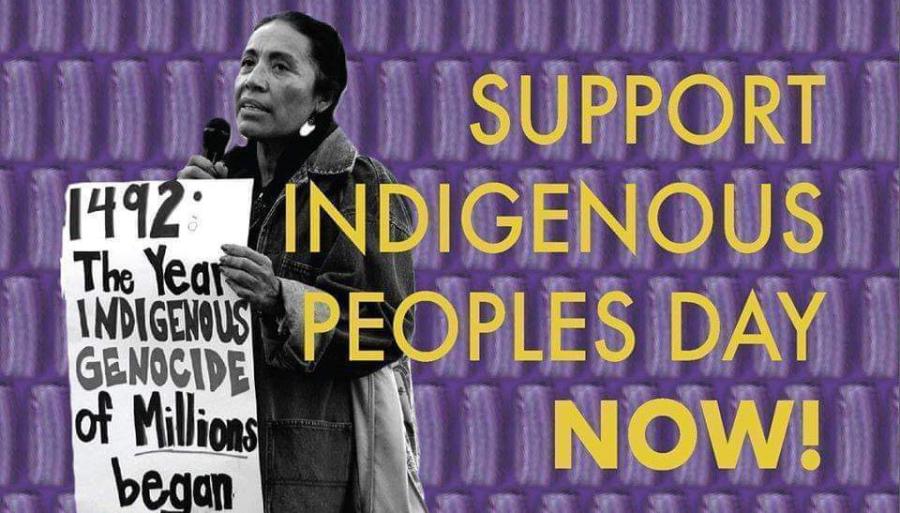

Recognition of the commemoration is essential, Carmen said, “It's important for all of us working internationally to recognize how this movement started, and what was sacrificed in order to bring it about. It wasn't easy. People were cold and shivering today on the island. And it was a beautiful sunrise ceremony. We had Indigenous speakers, presenters, dancers and drummers from literally all over the world. All the way from New Zealand and Hawai’i to Arctic Village, Alaska, [and] Ecuador.” And there was music, “Celebrating is another example of how we've been able to change the mentality of the world. Just last year—San Francisco decided to declare Indigenous Peoples’ Day instead of Columbus Day.” There are “myths of the pilgrims,” Carmen explained. Thanksgiving, for example, “was proclaimed by the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony to celebrate and give thanks for a massacre of the people during their green corn ceremony. Over 700 killed, and then the settlers—the Pilgrims—declared a day of Thanksgiving. So what we all learned in elementary school, dressing up like Indians and Pilgrims and eating turkey and such things you know is another very harmful untruth of history that we try to challenge not just for our own Indigenous kids, but [for] every single child in the United States [who] should know and own that history so that we don't repeat it, so that we can make amends and make corrections.” The declaration of Indigenous Peoples’ Day in San Francisco “was really important because of the show of solidarity with the Indigenous Peoples of California. There are many California Indian peoples from Northern California that suffered incredible genocide in the California Gold Rush and the policies of extermination that were officially the policies of the state of California. It's really important for us when we do the events for Indigenous Peoples’ Day.”

Indigenous Peoples’ Day, to Lapointe, is about more than just education, but about community. It “is a time to really come together as a Peoples and re-energize and refocus our vision, and recommit ourselves to this global movement that is Indigenous Peoples” and their rights. But, rather than being a “political identity,” Lapointe sees Indigenous Peoples more as a “sleeping giant of 375 million Indigenous people throughout the world, that is 375 million gifts, strengths, and possibilities. We come together on a spiritual foundation, much like a prayer that was done this morning, because that's what the braids together the world Indigenous community, international and local, as distinct Peoples. We want to let the broader community know that we're still here and we come together, [and] we always use these cultural and Indigenous ways of life.” LaPointe is working in collaboration and partnership with Indigenous Peoples and youth to host a pre-summit parallel event on water at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in April, called, Mni Ki Wakan (Water is Sacred). They are building a global Indigenous community that will convene in the annual Mni Ki Wakan: World Indigenous Peoples Decade of Water (mnikiwakan.org), held each August.”

“We're in for more,” said Gonzales, speaking of what lies ahead. “And we have all the sacred colors working with us, and we have one common goal, and that is to protect the coming generations by protecting Mother Earth, and living more sustainably, and realizing that the climate change is the big threat to us all. Mother Earth will go on. But other species are threatened. We encourage people to register to vote. Vote local, regional, and national, particularly in 2020. And also the U.S. Census count—everybody needs to be counted, particularly here in North America, [because the Census is] translating into federal dollars, which go to Indigenous or Native American health programs, education, and the like. So that's a big message that comes forth from Alcatraz.” Carmen is presently working with the UN General Assembly “to declare a decade of the world’s Indigenous languages.”

The commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the occupation of Alcatraz is another stepping stone in the path toward greater international recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ rights, cultures and histories. Much like the historical moment it marks, the commemoration will inspire future generations and continue the legacy of Indigenous Peoples’ activism.

Top photo by Rochelle Diver/ International Indian Treaty Council.

--Miriam Anne Frank has worked on Indigenous Peoples’ issues for IPOs, NGOs, international organizations and foundations for over two decades and is currently at Amazon Watch. She lectures at the Department of Cultural and Social Anthropology, University of Vienna where she teaches on these issues and their inter-relatedness to human rights, environment and development.

Alexandra Carraher-King is an intern at Cultural Survival.