By Edson Krenak Naknanuk

Displacement and human rights violations have become a tool to punish the Quilombola Peoples’ identity and reinforce structural racism and impoverishment. This article denounces the Brazilian State’s violations against Quilombola Peoples, known in English as Maroon Peoples, which are part of a wider strategy for demographic reengineering on Indigenous and Quilombola lands for attaining political and economic interests.

During the past few months, I have followed the situation of many Indigenous and Quilombola communities in Brazil with a particular interest in the issue of human rights and their territories and protection during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A case arose in which the Brazilian Navy undertook serious - unimaginable - and repeated violent actions towards the Quilombola Peoples in the Brazilian State of Bahia. I contacted the community and spoke to their leader, a brave and incredible woman whose words will reverberate throughout this text. I also spoke with one of the lawyers and partners to understand the legal context.

What shocked me the most and left me speechless several times during our conversations were the stories that Rose Meire dos Santos Silva told. She tells me how much she, her family, and her community have, in recent years, suffered several acts of disrespect, racism, and physical and moral violence. She shared videos – used in legal proceedings – that show Brazilian Navy soldiers beating her and her relatives while trying to enter their own homeland. The word she repeatedly uses to describe these acts is “torture”; it has been “a torture that goes beyond the physical, but that has psychological and social problems.”

When I told Rose Meire that I would write an article for Cultural Survival about their situation, she said thankfully: “You know the military dictatorship [which ended in the country in 1988] is not over for us, so your work is very important. We really need Cultural Survival’s support. We need support from all four corners of the world. I lost my father, my two brothers, and friends of the community, and today they're trying to take everything from us. I hope Cultural Survival is a door for us to share our story. Because I'm a Black woman, a Maroon, fisherwoman, and a rural worker. I'm a woman who fights to give my people freedom. I'm a mother and a sister of 16 siblings. My struggles are so our children and grandchildren do not live the psychological and physical torture of racism that we suffer today...We are a majority of women in the community who struggle to survive.”

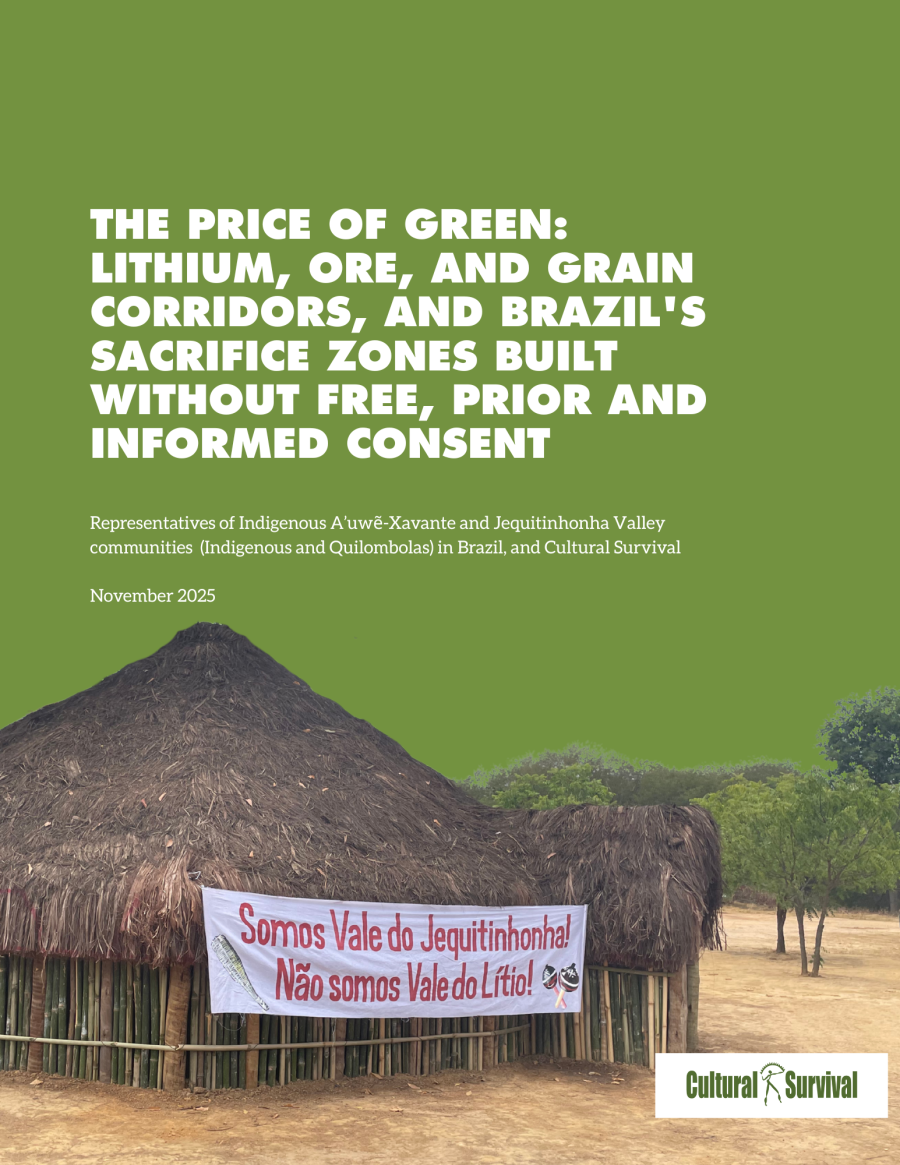

Quilombola protesting: “Rivers, mangroves, fish and workers at risk of extinction” says the sign. Image courtesy of Quilombo Rio dos Macacos

Who are the Quilombola Peoples?

The Quilombolas are the descendants and remnants of communities formed by enslaved Black and Indigenous Peoples who fled the cruelty of slavery and took refuge in the woods between the sixteenth century and the year 1888, when slavery was abolished in Brazil. Known as “Maroons” in the English language, Quilombola originates from the term kilombo, or quilombo, in the language of the Bantu people from the African and now Portuguese-speaking country of Angola and means resting place site or home camp. Unfortunately, resting is what they have not had since the Brazilian Navy became the neighbors and invaders of their lands. In Brazil, Quilombola is the person who inhabits the quilombo.

Throughout Brazilian history, several quilombos have been recorded, some with a large number of inhabitants. The Quilombo dos Palmares, for example, which was actually formed from a set of 10 quilombos near each other, came to have an estimated population of 20,000 inhabitants in the seventeenth century. According to a survey by the Palmares Cultural Foundation, there are 3,524 of these communities, but according to Quilombolas themselves, the total number may reach 5,000. The Palmares Cultural Foundation is a public agency linked to the federal government and, like The State Indian Foundation, FUNAI, for Indigenous Peoples, is responsible for the protection of Quilombola cultural heritage.

Quilombo Rio dos Macacos: What is happening?

Rose Meire’s ancestors moved to the Rio dos Macacos, in the northeastern part of Brazil 200 years ago. Currently, the community consists of about 87 families, with approximately 400 people. Since 1950, the Brazilian Navy "began the process of invasion of the traditional territory belonging to the Quilombola community of Rio dos Macacos for the construction of the Dam of the Macacos River, and then with the installation of the Naval Village of Aratu, a residential condominium where military people live with their houses with swimming pools, and all facilities in a comforting condominium," in Meire's words.

Rose Meire conducting a meeting in the quilombo to discuss the next steps after the trial. Image courtesy: Quilombo Rio dos Macacos.

This situation, in which the Quilombolas never had a voice nor participation, generated various conflicts, episodes of expulsions, damage to property, and physical and sexual violence. It is worsened by the lack of access to essential public services, such as health care systems, education, etc. When any assistance is needed, like an ambulance to enter the territory, it is not allowed by the Navy officers, for the Military institution built a guarded entrance to the land.

Rose Meire and others have sent me a series of reports of violence perpetrated over the years, such as shots fired by a military man at a community member in 2012 and the assaults on her and the community`s members. In one of those episodes, for instance, a video (see the image below) shows the Navy officers at the entrance to the Naval Village taking Rose Meire out of the car by force in front of her children and relatives. The various acts of threat, harassment, and even murders of other community`s members have been happening for years.

While trying to enter into their own land, the Navy officers take by force Rose Meire, who refused to leave the car, and put her down on the ground. They wanted to arrest her. Photo: Public archive and 2017 available at Josias Pires, Quilombo Rio dos Macacos - O Filme.

“They are killing us: torture, death and abandonment”

Rose Meire’s father suffered physical violence before undergoing a fatal heart attack in 1995. His death came due to the ambulance’s inability to access his home, one example of the hardness with which the Brazilian Navy has treated the community. Two of Rose’s brothers were also murdered in the region and the justice did not proceed with the investigation, because it was the community accusing the Naval soldiers.

In addition, and after five decades of legal battles, having victories that lasted a short time, the justice system seems not favorable and biased. Many times, decisions have been arbitrary; sometimes judges have taken actions on Sundays or holidays when the community could not react promptly. These violations, although not supported by the text of the law, were not punished, nor completely resolved or mitigated in the decisions of the courts.

Legal Weapons

1988 – The Federal Constitution states the cultural recognition, rights to lands occupied by remnants of the communities of the Quilombolas (art. 5, §3 of the CF/1988).

2002 – The National Congress through Legislative Decree No. 143 of June 20, 2002 ratifies Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization – ILO and promulgated by the President of the Republic through Decree No. 5,051 of April 19, 2004. It creates legal protections for Indigenous and Quilombola Peoples.

2003 – The delimitation of the territory of the Quilombola community Rio dos Macacos is based on Article 11 of decree 4.887/2003 and article 16 of Normative Instruction 57/2009.

2011 – The Public Prosecutor (MPF) conducts Civil Inquiry No. 1.14.000.000833/2011-91, which monitors the situation of conflict experienced by the Quilombola Rio dos Macacos Community, which claimed, on several occasions, to be the target of coercive actions (by the Naval institution) in the intention of expelling families living there.

2012 – The MPF agency issued a recommendation to the Command of the 2nd Naval District of the Brazilian Navy, aimed at inhibiting the practice of acts of physical and moral embarrassment against Quilombolas.

2012 – The conflict gained even more strength after the decision of the Federal Court in Bahia that ordered the eviction of the area by the Quilombola community. The MPF appealed presenting instrument injury before the Federal Regional Court of the First Region against the decision.

2014 – In August 2014, Official Report (RITD - INCRA) was published by State Agency in the Official Gazette by, identifying 301.3695 hectares of Quilombola land, and regularizing an area of 104.8787.

2017 – The Quilomba story with audiovisual evidences (used in the court) of the local conflicts was launched in the documentary Quilombo Rio dos Macacos - The Film directed by Josias Pires).

2020 – On February 8, the Supreme Court decided to keep the presidential decree that regulated in 2003 that the demarcation of the lands of Quilombola communities as constitutional.

2020 – Quilombola community Rio dos Macacos receives the land title - "It is not a simple document that we will sign, it is our letter of Manumission" (Rose Meire).

2020 – The Brazilian Navy undermines the Court Decision by impeaching Quilombola people to access the water.

2020 – Quilombo Rio dos Macacos appeal against repossession of the dam by the Navy.

2020 – The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) adopts Resolution 42/2020, by which it granted precautionary measures to members of the Remnant Community of Quilombo Rio dos Macacos. The applicants alleged that the beneficiaries are at risk due to threats, harassment, and acts of violence perpetrated against them in the context of their dispute for recognition of their territory, and in view of the potential collapse of the dam in Rio dos Macacos, close to the territory. The State must protect them from threats and acts of harassment and violence committed by both state officers and third parties, pursuant to international law of human rights; consult and agree upon the measures to be adopted with the beneficiaries and their representatives; and report on the measures adopted in order to investigate the facts that led to the adoption of this precautionary measure and thus avoid its reoccurrence.

Rio dos Macacos: A Failure of Justice

Community representatives received the title. Rose Meire signs the document. Photo courtesy of INCRA/BA

“The only thing we want is access to water”

In July of 2020, the remaining Quilombola community of Rio dos Macacos received the title to its lands, as shown in the Legal Weapons section, on the border between the municipalities of Salvador and Simões Filho, in the state of Bahia. Yet, the victory, following decades of struggles, came with a bitter taste. The Brazilian Navy has always tried to expel the Maroons from their territory, and when it has not succeeded, it has used its political influence to interfere in court decisions. In mid-October 2020, at the Seventh Federal Court in the state of Bahia, a judge on duty on Sunday accepted a request from the Navy to prohibit the Maroons from accessing the waters and the dam that exist on the Quilombola land and whose use was shared until then. This order of repossession in favor of the Navy levies a fine of 1,000 reais ($250 USD) per person per day who is caught using the dam area and the water of the river. Without this access, the Quilombola are prevented from having potable water, a place for traditional fishing, resources for their families’ gardening, or even places for carrying out religious services, among other losses. Thus, even though the final decision of the Brazilian justice consolidated the right of the Quilombolas to the land where they have lived for more than 200 years, the privileges of ruling the territory and controlling the water supply stayed with the Navy. The Quilombolas lost access to essential resources for life and traditional forms of economy, social life, and religion, because the verdict divided the land of the Quilombolas. The legal battle therefore resumes for access to water.

Rose Meire told me that after that trial, "the women of the community were surprised by the truculent actions of Marines and other agents of the Brazilian Navy, who prevented fishing and placed a plaque in the territory, near the river, prohibiting the use of water by the community. The military has been prowling our homes at night, staring at our doors with guns in hand, frightening us and causing terror in the community. Also we are not allowed to renovate and build our houses. They threaten us.”

The AATR, an advocacy organization that supports peasants and defends the Quilombola in court, points out that this "partial entitlement opens the gap for the Brazilian Navy to violate even more fundamental rights and block access to water. Although it has been titled to the Navy, the dam and water reservoir are inside Quilombola territory.

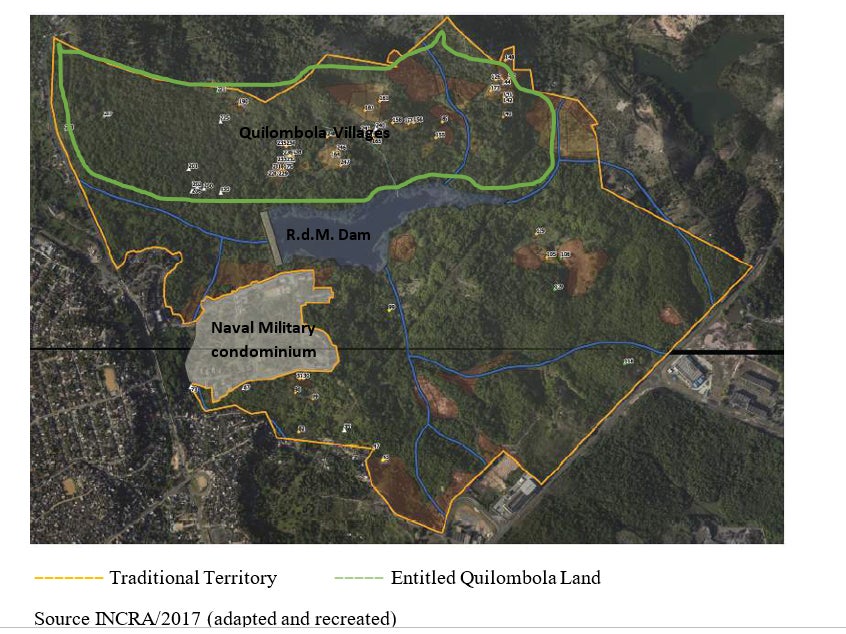

The map above shows how the military facility built a guarded wall preventing the community from accessing the river. Proof of Quilombo residents’ historical use of the waters of the dam is documented in the Technical Identification and Delimitation Report (RTID)" produced by the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA), which is a federal government authority of the public administration of Brazil.

Although the territory identified in the RTID has a total area of more than 300 hectares, INCRA has granted title for only 1/3 of the area - that is, only 98 hectares - to the community. These 98 hectares are entirely without water sources or any water system for the community, for even state agencies cannot install or provide such infrastructure on that land due to an arrangement imposed by the Navy. This is an obvious strategy to make life in the community unviable since the main source for life conditions is the river. The Brazilian Navy acts, as do many other state agencies and branches of government, to implement a violent dispossession of lands and rights with human rights violations and terror.

What makes the situation worse is that this all is happening during the delicate moment that traditional communities face amidst the global pandemic of COVID-19. As Cultural Survival has reported previously, the traditional communities in Brazil are overlooked and abandoned by the Bolsonaro’s governments, changes, and new public policies.

Structural Racism

Emicida, a Black singer who supports the community, stated in the documentary “Rio dos Macacos” that “poverty, violence, and lack of rights have the same color: Black.” The lack of public policies, the inadequate State measures to protect Indigenous and Black Peoples, the slow and weak justice for them, and the multi-dimensional violence against them characterizes what has been called structural racism in Brazil.

The necessary reparations for those victims of the enslavement and devastation of colonialism not only require economic and territorial protections but also entail the eradication of persistent structures of racial inequality and awareness of a systemic and wide racism and discrimination by State institutions.

The UN Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Forms of Intolerance, Dr. Tendayi Achiume, affirms: "Although the Government of Brazil has tried to address the theme of structural racism against Brazilians of African origin, the persistent and irremediable effects of enslavement and colonization continue to permeate Brazilian society. [...] Afrodescendant Brazilians face racial discrimination and institutional exclusion, and remain in the last place on the socioeconomic scale. Compared to Brazilians of European descent, those of African descent support poorer social and economic conditions, including lower average admission, lower life expectancy, inadequate education and housing, higher unemployment rates and greater food insecurity. Moreover, as a result of ingrained and state-sponsored discrimination, it continues to criminalize and subject Brazilians of Afrodescent to prison and brutal violence disproportionately, which includes extrajudicial executions.

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 1 A Quilombola house which cannot be improved or reformed because the Marinha do Brasil does not allow them. Collective archive/2014.

The State knows the importance of maintaining dialogue with the traditional communities, in the terms established in ILO Convention 169, and has conducted various meetings; however, the decisions were not taken seriously. As far as the expectations, needs, and rights of Quilombolas and Indigenous Peoples are concerned, the way the government has conducted the protocols is inadequate.

Quilombolas and Indigenous Peoples

There is a historical proximity between Quilombola and Indigenous Peoples with regard to the impacts of colonialism and the way the State reproduces and maintains an unfair social system against these peoples. The two groups live simply and integrated with nature, taking most of their livelihood from the land. However, with the advance of urbanization, the impersonal policies of the State that ignore the context and culture of the populations themselves, and agribusiness and unsustainable extractivism, the way of life of these communities and their preservation are in danger.

Rose Meire and Dona Olinda, another local leader of the Rio dos Macacos quilombo, hope that the international community can help them to pressure the Brazilian government and Marinha do Brasil, the Brazilian Navy, to guarantee their rights and access to water.

Like Indigenous communities, Quilombolas need support, first to give visibility to their causes, struggles, and the innumerable acts of violence they suffer, and finally to enjoy the justice and peace they deserve after historical violence.

--Edson Krenak Naknanuk is an Indigenous activist and writer in Brazil and a Cultural Survival consultant. Currently, he is a Ph.D. candidate in Social and Cultural Anthropology with studies in Legal Anthropology at Vienna University, Austria. He is also a teacher. He loves interacting with children and youth and preparing them for a better world.

Special thanks to “Duda”, a former AATR lawyer and new good friend, and especially to Rose Meire dos Santos do Quilombo Rio dos Macacos for the inspiring conversations and for trusting Cultural Survival with her story.