On November 18-20, 2022, the Richmond, Virginia-based Pocahontas Reframed Film Festival once again raised issues of Indigenous sovereignty, climate change, decolonization, language reclamation, and the Indigenous past/present/future through films, panel discussions, readings, and live performances. One of the highlights of the festival was a panel “Reading from the 4th World,” which focused on a four-episode science fiction fantasy television series featuring Pocahontas as a lead character, along with another important Native American historical figure, Joseph Brant.

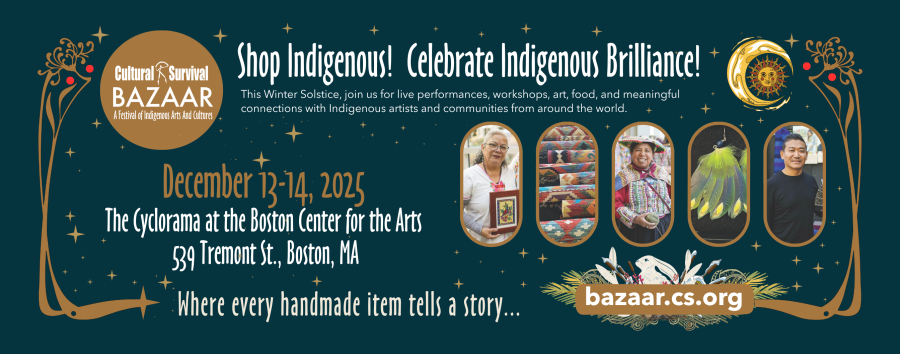

Presented by Iroquois Arts, “The 4th World” is a historical exploration that envisions a future world with Pocahontas and Brant, historical Indigenous figures who continue to evoke strong emotional reactions among both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Writers/filmmakers Shelley Niro (Mohawk, Six Nations) and ElizaBeth Hill (Mohawk, Six Nations) traveled to U.S. reservations to meet with Pamunkey and Mattaponi descendants and to search through their museums, libraries, and family archives.

“Reading from the 4th World” panel poster.

They also interacted with Iroquois Traditional Knowledge keepers and scholars in a quest to unravel truths and discrepancies between documented history and stories from descendants and knowledge keepers. Their research inspired them to create fictional stories as a way to present historical information. Additional scriptwriters Jordan Wheeler (Cree, Ojibway, Assiniboine) and Darlene Naponse (Anishinaabe, Atikmeksheng, Anishnawbek) were invited to bring in other Indigenous historical characters to the storylines.

Three years were spent accessing historical documentation about the main characters to a mixed degree of success. For example, Pocahontas was kidnapped by Captain Samuel Argall when she was a young woman but Niro and Hill could not find any log books that reference it, while copies of John Smith’s diaries with fictionalized accounts of Pocahontas’s life are numerous. The fact that Pocahontas was a nickname and her given name was Matoaka is often overlooked, as well as her first marriage to a Native person named Kocoum, with whom she had a son prior to her kidnapping, and her later marriage to the Englishman John Rolfe. Similar discrepancies can be found in documentation about Brant and the Treaty of Paris, which involved the loss of the traditional homeland of the Six Nations.

“Reading from the 4th World” panel. Photo by Shelley Niro.

Niro laments the fact that non-Indigenous interviewers seldom give credit to oral storytelling or acknowledge that Indigenous history can be told more truthfully by Indigenous people. She counters, “We would like to tell those stories in a way that is creative, interesting, fun, and challenging while encompassing the past, present, and future in the telling.”

“Reading From the 4th World” featured actors Katrinah Carol Lewis, Landon Nagel, Shinji Elspeth Oh, Trevor Lawson, and Toney Cobb selected by Director Nathaniel Shaw from The New Theatre in Richmond, Virginia as well as Darlene Naponse, one of the writers. The writers have not yet approached any producers about developing their scripts into a series. “I cannot tell you enough how the actors' presence was impactful on hearing the scripts read,” Niro said.

Dancers from the Upper Mattaponi, the Mattaponi, Chickahominy, and Nansemond Tribes. Drum Group is the Adamstown Singers from the Upper Mattaponi, Mattaponi, Saponi, and Tuscarora Tribes. Photo by Julian Kunnie.

Shifting back and forth from the 1600s to the 21st Century and an imaginary future was a challenging, insightful, entertaining, educational, and inspiring experience for the audience. Pocahontas/Matoaka/Rebecca (her baptized Christian name) speaks contemporary English, Elizabethan English, and Indigenous languages connected to the Powhatan peoples. In one scene, at the age of 20, the character Pocahontas speaks the Mattaponi language of her mother’s people. Jumping several centuries ahead, Pocahontas and Brant witness the destruction of the twin towers in 2001 while speaking in contemporary English. Brant states, “The destruction I witness is my fault for not taking action,” which alludes to Brant’s friendship with the Duke of Northumberland and Brant’s role as Ambassador for the British and his role in the infamous Treaty of Paris.

Other time-traveling scenes that may seem controversial to academic historians or conservative Pamunkey and Mattaponi Tribal members include the use of Matoaka’s Christian name, Rebecca, for the character that dresses stylishly, “walks with purpose and posture,” lives in a minimalist, posh London apartment. In one scene, Rebecca removes her clothes, curls into bed with a beautiful Black woman named Zoe, and kisses her. The character Zoe appears in several scenes during various time periods with Rebecca and Matoaka.

In 1610 Jamestown, a young Pocahontas walks in tall grasses, speaks to sea shells, talks to the trees and animals, runs through the forest, and walks into water. Jumping ahead to her 30s, Rebecca is back in the 4th world at the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford University, where in this series (and in our “real world”), her father, Chief Powhatan’s, historic mantle is displayed. Addressing her colleagues and students, this futuristic Rebecca discusses colonialism, first contact, and the importance of tobacco. At Graves End, England, where the historic Pocahontas is buried, Matoaka and Brant share thoughts telepathically.

Flutist Darren Thompson (Ojibwe/Tohono O’odham) from the Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe Reservation in Northern Wisconsin. Photo by Julian Kunnie.

The imagined future also includes scenes in Alaska where a Russian invasion is imminent at an outpost on the Bering Strait and Matoaka and Brant are wearing military uniforms. For science fiction buffs, these scripts that flow seamlessly through time will be a must see, especially for Indigenous Peoples who are tired of seeing themselves mainly in the historic past, sometimes in the present, but seldom in the future. At the culmination of the viewing, Niro expressed her gratitude to the Film Festival Board’s Director, Bradby Brown (Pamunkey), “for letting us take the stage and deliver a part of our work. He is progressive and wants to keep PRFF moving in that direction,” she said.

The following is a brief synopsis of a few of my favorite films and readings from this year’s Pocahontas Reframed Film Festival:

“K’ina Kil: The Slaver’s Son” (2015), directed by Jack Kohler, is a fictionalized account of true events involving Tlingit Alaska Native women who were sent to Fort Ross, California as sex slaves in the mid 1800s. Many of the mixed race children born to Indian women through rape and sex trafficking were left behind at the end of the California Gold Rush. K’ina Kil is an Indigenous term for children of unwed mothers who were often unrecognized by either Indigenous or white people. Kohler cast his daughter and hired other Native American actors at his own expense after refusing to cast the all-white actors suggested to him by mainstream producers. The film was shown at the NYC Tribeca Film Festival and won best short at Cannes.

“Long Line of Ladies” (2022), directed by Rayka Zehtabchi and Shaandiin Tome, focuses on the resurgence of the Ihuk puberty ceremony of the Northern California Karuk Tribe. As Indigenous coming-of-age puberty rites for boys and girls are almost extinct in communities around the world, viewing “Long Line of Girls,” which documented a series of events where teenagers “start out as girls and come out as women” four days later along the Salmon River, was eye-opening for many in the audience.

The themes of the short film “Saging the World” (2022), produced by Rose Ramirez, Deborah Small, and the California Native Plant Society, and the reading by Diane Wilson (Dakota Nation) of her recent novel, “The Seed Keeper,” both featured on the same day, are very interrelated. The film chronicles the desecration and exploitation of Grandmother Sage (salvia apiana) by consumer capitalist Western cultures that do not follow traditional, Indigenous ways of harvesting and using the plant. Wilson discussed the relationship between her fictionalized characters and her work with the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance. Both the film and Wilson’s reading emphasized that the ancient original agreements between seeds and humans are not being honored in contemporary times.

L-R: Shelley Niro (Mohawk), writer/filmmaker of “The 4th World” and Pocahontas Reframed Film Festival Board member with Phoebe Farris (Powhatan-Pamunkey). Photo by Julian Kunnie.

“Bring Her Home” (2022), directed by Leya Hale (Sisseton Wahpeton Dakota and Dine’), highlights three Native women—an artist, an activist, and a politician—who tirelessly advocate for their missing and murdered relatives, primarily women. Of importance to many Indigenous women is how the #MeToo movement ignores missing Native women, who are often found long after they have been raped and/or murdered. Artworks are featured in the film from the exhibitions, “Bring Her Home” and “Sacred Women of Resistance.” The documentary highlights North Dakota State Rep. Ruth Buffalo (enrolled citizen of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation) who advocates for MMIW (Missing Murdered Indigenous Women) legislation. Minnesota Lt.Governor Peggy Flanagan (White Earth Band of Ojibwe) also appeared in the film.

“The Osage Murders” (2022), produced by Dan Bigbee and Lily Shangreaux, is a historical documentary from the Indigenous perspective about events that occurred on the Osage reservation in the 1920s when Tribal members were mysteriously dying at alarming rates. The local white authorities dismissed these deaths as accidents, suicides, or the result of alcohol poisoning. At the time, the Osage were known as the wealthiest people on Earth because their reservation was located on land above the largest oil field in the United States.

Bradby Brown (Pamunkey), Board member and Chair of the Pocahontas Reframed Film Festival. Photo by Julian Kunnie.

The documentary references the late author/journalist Charles Red Corn (Osage Peace Clan), whose 2002 novel, “A Pipe for February,” takes place during these turbulent times. The novel’s main character describes the 1920s from a traditional Osage perspective, taking on theft and murder for profit as well as the challenges that the wealthy Osage faced trying to adjust to the Roaring Twenties. Red Corn’s novel predates David Grann’s 2017 book, “Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI,” which is falsely promoted as the first book about the Osage murders. During the film’s follow-up discussion, producers Bigbee and Shangreaux expressed that they are glad their documentary was produced and viewed before the upcoming film based on Grann’s book.

The last film shown on the last day of the festival, “Call Me Human,” (2020) directed by Kim O’ Bomsawin (Abenaki), won Best Canadian Documentary at the International Film Festival Vancouver, Best Canadian Documentary at the Calgary International Film Festival, and the Audience Choice Best Documentary at Cinefest Film Festival. In French with English subtitles, the film follows Innu writer Josephine Bacon across Montreal, Pessamit, and the Canadian tundra as she shares her life reflections and stories, leading a movement to preserve the language and culture of her people as well as acknowledging the language and culture loss of many other Canadian Indigenous Peoples.

Viewing films from 9:00 a.m.-9:00 p.m. for two days and from 9:00 a.m.-5:30 p.m. on the third required a lot of endurance for us in the audience. It is a marvel how Film Festival Board member Chief Lynette Allston (Nottoway), the emcee responsible for introducing each film and its subsequent discussions, handled it with such grace, humor, and insight.

--Phoebe Mills Farris, Ph.D. (Powhatan-Pamunkey) is a Purdue University Professor Emerita, photographer, and freelance art critic.