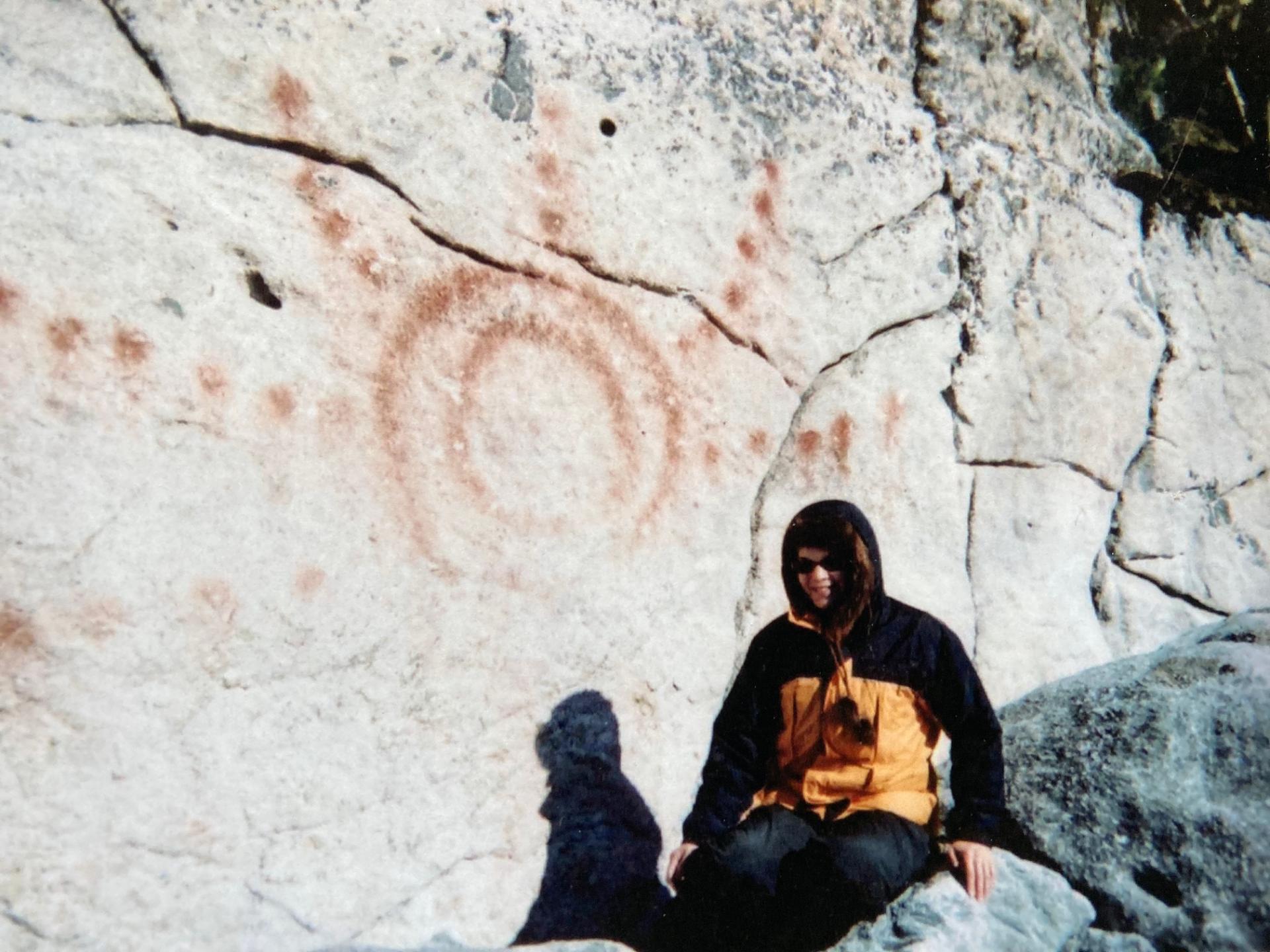

As the ooligan came in, their fluid, silvery forms filled the glacier-blue river. I had never seen anything like it—it looked as though you could have walked up and across the water on their backs. The absolute beauty of the Unuk River is breathtaking. It’s wild and unruly, and I was in love. After we had caught what we needed and started heading for Ketchikan, we left a living river in our wake. My family has been the river’s customary caretakers for over 10,000 years. Our crests of the rising sun are seen throughout the river. These pictographs declare we were there then, we are here now, and we will be there as long as this river flows.

During the end of the last ice age, the Unuk was a refuge and a corridor between the coast and the interior of British Columbia for the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian Peoples, a lifeway leading them back home again. The river feeds the temperate rainforest of the Tongass and sustains a tremendous variety of wildlife, including migratory birds and four species of salmon. It is known for its rich run of ooligan, the slender, oily fish that we have relied on since time immemorial. My mother and father, Cindy Wagner and Louie Wagner Jr., have fished ooligan on the Unuk for over six decades. My father is the “ooligan man” who provided the fish for Metlakatla, Prince of Wales Island, and Ketchikan each spring. My mother is known as the “grease lady” for having mastered the art of making highly sought-after ooligan grease.

It was a crisp spring evening when we reached the Ryus Float in Ketchikan. As our boat approached, lines

of people were waiting for their share of the savior fish, singing and cheering for us as we docked. I vividly remember the excitement, joy, and their bright smiles. Ooligan brought everyone together and marked the arrival of spring. Everyone was happy. That was 21 years ago and the last time we fished on the Unuk. I was granted a small window into our traditional way of life. We lived with and cared for the land and water. We respected and cherished the countless forms of life that it sustains.

Unuk River in the early 1990s. Photo by Louie Wagner Jr.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, we started noticing changes around the river. My mother found 50-gallon drums and debris washing up on the riverbanks. There was more silt in the water, and its hue was no longer glacier blue. As time went on, fewer and fewer ooligan came in. Eventually, they were nearly gone from the Unuk. Salmon, too, began disappearing at an alarming rate, along with other wildlife. The law officials told my family that we were no longer allowed to fish. It was a devastating blow to my family and the entire community.

Back then, we didn’t know that there were mines operating above the Unuk and that ooligan had left the river in search of cleaner water. Unlike salmon, ooligan are not tied to their rivers of birth. Despite our deep ties with the Unuk River and our traditional lands straddling the U.S.-Canada border, we’ve been left out of decision-making processes. Mining development in the headwaters of our culturally significant Unuk, Taku, and Stikine Rivers is expanding at an alarming rate. At present, two hard-rock mining projects are operating with three others fully permitted, two in the process of permitting, and a growing number in the advanced exploration stage. The mining operations are already generating massive amounts of toxic waste, which poses a significant threat of polluting downstream waters with heavy metals.

For us, the people of the Unuk River, the situation is further compounded by the fact that Eskay Creek, one of the mines that operated in the 1990s, is being permitted to re-open on a much larger scale. The plan includes two open pits and toxic mining waste dumped into what were natural lakes swelling behind tailings dams. The design of these structures calls for maintenance into perpetuity; in other words, forever. This is starkly against our values of leaving these lands and waters pristine for our children’s children.

Ooligan (Thaleichthys pacificus) is also known as eulachon and candlefish. Photo source: Wikipedia.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, endorsed by Canada in 2010, requires Canada to recognize our rights and interests in territories that predate the U.S.-Canadian border. Our Tribal and First Nations communities in both Alaska and Canada have the right to say what will happen on our lands. In 2014, 15 Tribal Nations in southeast Alaska formed a commission set to protect our Tribal lands, waters, and ways of life from mining impacts. The Southeast Alaska Indigenous Transboundary Commission (SEITC) is in direct engagement with British Columbia over the mining processes and is building a case for Participating Indigenous Nation status for our member Tribes. We are the first U.S. Tribes to ever seek this recognition in Canada.

Alaska state legislators have urged British Columbia to consult with us during the processes to permit new mines, writing, “The U.S. and Canadian governments and the Indigenous Peoples on both sides of the border have a responsibility and opportunity to better manage these shared watersheds in a constructive and cooperative manner. We hope the B.C. government shares our conviction that this can only be accomplished with the Alaska Tribes of the SEITC as meaningful participants.” SEITC has challenged Canada’s actions before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), alleging that Canada’s failure to regulate and prevent threats from large-scale mining operations in British Columbia constitutes a violation of SEITC member Tribes’ internationally recognized human rights. The IACHR admitted the petition in October.

Lee Wagner by her family crest on the Unuk River. Photo courtesy of Lee Wagner.

Before these devastating mines upstream from us begin their operations, my mother wants to fish the Unuk River with her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren this spring, as we used to, fulfilling our inherent rights given by grandmothers from generations and generations ago. “Maybe have it documented as a lost way of life,” she says. The mining industry has infiltrated the headwaters of our sacred waterways. If we allow this to continue, the devastating true cost to Indigenous Peoples will become evident once the land has been exploited and the boom inadvertently busts. As a mother, this is not a legacy I wish to leave for my children.

Canada must fulfill its obligations to international human rights and adhere to the principles outlined in the Declaration. Collaborating with Indigenous communities, who have been safeguarding these rivers for countless generations, and valuing their ancestral wisdom, is true progress. By honoring the lessons passed down by our foremothers and drawing strength from our ancestors, we can stand up against the destructive forces that have taken so much from us. As our commission challenges one of the most powerful industries in the world, in my heart, I see our river once again running clear and glacier blue, our savior fish saturating its currents, and my family fishing on the Unuk again.

--Lee Wagner (Tsimshian, Haida, and Łingít of the Niisk’iyaa Laxgibuu/wolf clan) is Assistant Executive Director of the Southeast Alaska Indigenous Transboundary Commission. She grew up fishing with her family throughout southeast Alaska and spent much of her time learning her way of life from her parents and Elders. She has harvested from, and helped take care of, the Unuk River alongside her family, who have done so since time immemorial.

Top photo: Petroglyph at the mouth of the Unuk River. Unuk River's Tlingit name, Jòonax_, translates as “revealed through a dream,“ referencing an ancient time before the Great Flood and the dreams of a Nèix_.adi man who had visions of the river and urged his clan to seek it out.