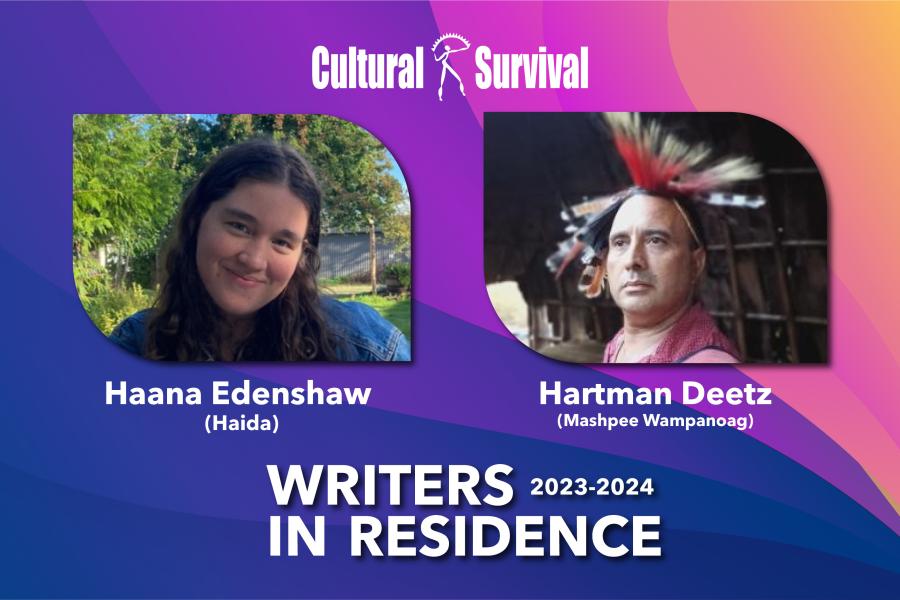

The Heiltsuk Nation in Bella Bella, British Columbia, Canada, is integrating Traditional Knowledge into an AI-based tool to track salmon migration to help them assert their land rights and steward fishery resources in their territories. Indigenous Rights Radio Program Coordinator, Shaldon Ferris (Khoisan), recently spoke with William Housty (Heiltsuk), Associate Director of the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department, about the project.

William Housty. Photo by Mark Godfrey.

CS: Tell us about the importance of salmon in your culture.

William Housty: Salmon is a cornerstone of our culture; that relationship makes up our identity. We’ve been known in the past to describe ourselves as Salmon People, and I honestly believe that we wouldn’t be here today if it wasn’t for salmon. Salmon being available and abundant to our ancestors and through the present day helped [our People] survive some very difficult times through the years. Our first-generation stories that talk about how we came into existence involve the salmon and the creation of the salmon. We’re very intertwined with them culturally.

CS: What threats do the salmon populations face today?

WH: Climate change is a huge one. Different weather patterns are contributing to different conditions in the ocean that are affecting the survival of salmon. We also have an overabundance of some of the predators of salmon, like seals and sea lions. Over the years, our Heiltsuk people relied on salmon, seals, and sea lions as a part of our diet. That part of our diet has shifted, and as a result, we haven’t been harvesting as many seals and sea lions. Their population has gone through the roof, and that has a big impact on the salmon, both as juveniles and as adults. We try to strike a balance on overfishing and mismanagement. The management of salmon was taken over by the government years ago and was grossly mismanaged to the point where there’s next to nothing left.

CS: How has the management of the salmon shifted over time?

WH: Prior to western colonization, our people lived all throughout the territory and were managing things on a river-to-river scale—place-based management. Everybody lived next to a river, because that’s where the main source of food came from. When we all amalgamated together into the present day, the management shifted to the government because they manage on a larger regional scale.

We’ve seen a huge failure in the colonial management of salmon. Over time, as commercial fisheries took more and more and more, they didn’t understand (or care) about how many fish were actually needed to be in a river to keep the population of salmon sustainable. They just continued to harvest until there was no more. It was that mentality where you just take and take until there’s nothing left. It’s a very backwards approach to the traditional way of harvesting. We understand what’s there and that we need to have a certain amount of salmon in the river before we start to even think about harvesting for ourselves. We’re at the point where we’re restoring and trying to repopulate a lot of the previous salmon systems that have been devastated by that [colonial] management approach.

CS: How did the project of using Artificial Intelligence to track salmon migration come about?

WH: The whole use of AI, we kind of just stumbled upon it. In 2012, we established a traditional salmon weir in one of our key watersheds. At that time, we were catching both live adult salmon and juvenile smolt salmon. One was coming into spawn, and one was going out into the open ocean. We were tagging them with pit tags that sent a little sensor up to a satellite. As these salmon passed certain checkpoints in the river, they would send a notification that they had made it up to the spawning ground. That’s kind of where it started; we piloted that project coupling with our weir. We were seeing some pretty good results, and then we had an opportunity to pilot a camera project with AI at our weir. It is a traditional weir that concentrates the salmon to one portion of a fence that’s blocking off the river; when they go through the trap door, the AI would take a photo of the salmon. We were able to establish a very accurate count of every salmon that was passing through our weir. The first year was piloting that and getting to know the technology, training our people who are on the ground to use and maintain the technology. It’s very effective.

CS: How has the Heiltsuk Nation benefited from combining AI tools with Traditional Knowledge?

WH: The AI gives very accurate, real time results. When we’re making management decisions about certain salmon populations, we can have some certainty behind those decisions because we know that the AI is giving us a concrete number. If you were to go and stand on the side of a river that’s 30 feet wide, the chances of you counting all the salmon that pass would be very low, with a very high chance for error. When we utilize the AI we’re looking at specific numbers, and those are allowing us to make in-season management decisions. If we’re in the middle of salmon season and the AI is telling us that the numbers are low, we can shut any food or commercial fishery down on the outside for conservation concerns. On the other hand, if we’re having a great year, we might be able to open it for a little bit longer and still do it in a sustainable way. It’s giving us certainty when making decisions about sustainability within particular salmon populations.

We’ve really strived to dovetail western science and Traditional Knowledge. Being able to use the knowledge of Elders in the community to help concentrate efforts on particular systems or particular places within watersheds and being able to use some of the techniques, such as AI, to help us revert back to our traditional management systems, is really beneficial for us because we’re getting the best of both worlds. We’re in the process of publishing a paper right now that’s taking all the different approaches that exist and putting them all together into one so that we can get the best possible outcome. When you bring those two worlds together, you can tell a really powerful story and have some powerful results that bring you back to traditional management systems.

CS: What do you hope to see in the future with the advancement of technology and AI for salmon?

WH: There are thousands of creeks and rivers in the territory; this is just one of those thousands of creeks that are being studied like this. Having AI do some of the work on our behalf allows us to go to other places to establish [systems like] this, to reach out to other systems that need restoration, and be able to focus efforts there. If we’re able to utilize this technology on a broader scale while still being able to work on a watershed-to-watershed basis, we can go a long way in making better management decisions for salmon. What’s been lacking with the salmon for many, many decades is that decisions about them have been made by people in three-piece suits in Ottawa, not by the people who are here living with them and who understand them and are utilizing both science and local knowledge to make decisions about them. This technology, if we can utilize it and start to grow it more and more, it’s only going to produce more results and make us better managers and stewards of the salmon.

CS: What does the ethical use of AI look like for Indigenous Peoples?

WH: We’ve had this question before: is AI ethical? To us it is, because we’re not just taking AI and using it any old way. We’re utilizing our own Traditional Knowledge to inform AI. AI is turning around and helping us to gather information, and we’re making decisions based on that information. We’re not having some auto-generated decision made for us. We’re utilizing the technology of AI to help us make a management decision. That in itself is ethical, in that we’re not relying on the technology to make a decision for us. We’re relying on the technology to help us make an informed decision.

Monitoring salmon in river. Photo by Howard Humchitt. Inset: William Housty. Photo by Mark Godfrey.