By Abou Farman and Reynaldo Morales

On the eve of Peru’s Independence Day, on July 27, 2022, a coalition of Indigenous Shipibo Konibo communities and mestizo settlements traveled by boat to the lower neck of the resplendent Imiria Lake, to occupy the grounds of the regional government’s Conservation Area (ACR) station in protest against what they called years of unjust, restrictive and exclusionary imposition. What was imposed in the name of conservation, they say, has brought them only pains and no benefits. Following up on legal documents they had submitted, they asked that their communities be excluded from the conservation area and called for a meeting. Almost three months in, and after the Ministers of Environment and Agriculture have been dismissed by Congress, the stand-off continues. Whilst new central government appointees are in limbo and communities’ vigilance committees retain control of the entrance to the lagoon, the regional government, with the backing of USAID-funded NGOs, has tried to divide the communities with presents and workshops, and money creating a potentially escalating conflict.

This is the latest incident in the increasing global tension between Indigenous communities worldwide and the interests of large well-funded international conservation movements accused of "green grabbing." If the case of the Virunga National Park in the Congo last summer (in which the state decided to commercialize the national park for oil exploration) sparked horror in international circuits, the Imiria case should offer some hope. The Indigenous recuperation of their territory from the conservation area should be lauded. For, as the communities stated, state-controlled conservation is serving as a façade for legal and illegal extraction activities. These activities have encountered an Indigenous-led resistance fighting to assert autonomy and self-determination in how they protect their own lifeways and the waterways of Imiria as an entire ecosystem. This comes at a critical turning point in the march of climate change and loss of biodiversity, when natural resources – in this case, fresh water and fish - in many parts of the world as well as regionally in the Amazon are contaminated or emptied of life. It’s in this context that the Indigenous organizations COSHIKOX (Consejo Shipibo Conibo) and the Guardia Indigena Shipibo Conibo have denounced USAID, with its NGO affiliates, for taking the side of the local government against both Indigenous and ecological interests (USAID has been similarly accused in a different park in the Congo in which indigenous Batwa villages have been destroyed by park rangers).

The recent problems started with a fishing proposal pushed by USAID-funded NGO Pro Bosque at the beginning of the summer. Or really it started long before, as the former Vice President of Coshikox Lener Guimaraes stated. It started 500 years ago with colonization. “Now,” he added, “they colonize by law, and they use us to colonize ourselves.” The Imiria conservation area was legally introduced in 2010, when the regional government and a group of international NGOs decided to impose the regional conservation area on top of existing and titled Indigenous communities, creating diverse conflicts. This process has escalated over the last two years, when Caimito, one of the Imiria communities, decided to assert their autonomous customary Indigenous governance and formed its own Guardia Indigena, with the goal to defend its own titled territory from poachers, coca farmers, land grabbers, and different organizations embedded in different legal and illegal formations around fragmented Shipibo territories.

Shipibo Indigenous Amazonian communities from Lake Imiria Protected Area peacefully occupy the Regional Conservation Area site. They have sustained their presence and asked the state to stop all activities. Photo by Bernabe Ventura.

But the uprising really caught on this July as a group of about 30 people, members and authorities from surrounding communities, marched out of five boats near sunset towards the ACR offices, waving a black and white Shipibo-designed flag, chanting "Imiria is not for sale, Imiria shall be defended" (Imiria no se vende, Imiria se defiende). Led by the recently formed Guardia Indigena of Caimito with support from the regional directorate of the Guardia and authorities from 9 out of the 13 caserios (settlements) and native communities that live under the conservation regime, they peacefully surrounded the offices, asking the official guardaparques (park officers) to leave. The offices, which were empty of goods, remained locked and untouched as the group camped outside overnight, setting up for a long blockade in order to pressure the regional government to respond. Over the course of the week, the numbers grew into hundreds.

The Toma, occupation, or as they say the reclamation of their own territory, has been long in the making as years of unjust administration have led to anger and resentment, as well as social and ecological problems in the lake region. The most serious allegations are that the conservation area was established without an adequate Free, Prior and Informed Consent process, and without a proper voting system as international law ratified by the Peruvian government mandates. A document released in Spanish on the day of the occupation summarized additional problems cited by the communities over the years, which include unjust fines and restrictions imposed on community members whilst the park administration has allowed both legal and illegal extraction of resources from the forests and lakes of the region. In addition, the communities claim, industrial fishing techniques and illegal coca production have contaminated the forests and the lake under the watch of the regional government. In short, the conservation area has failed in its goal of conservation whilst benefiting from an annual budget of 11 million soles of which the communities say they have seen virtually nothing. According to COSHICOX, since 2000 the regional government and environmental authorities have executed millions of dollars in projects with a consistent pattern of irresponsible management practices and lack of respect for the territorial rights and incorporation of traditional knowledge from the Indigenous communities in the decision making for the region’s conservation. Shipibo organizations argue against the perpetuation of a conservation model that excludes Indigenous Peoples in their own territories and forests.

Raul Amaringo Cruz, Head of the Indigenous Guard of Lake Imiria.

Raul Amaringo Cruz, Head of the Indigenous Guard of Lake Imiria.

The most recent affront came this summer in the form of what Jeremias Cruz, the head of the local Committee, called “the fishing trap.” The administration of the conservation area, along with the USAID-backed NGO ProBosque, began to visit communities to try and persuade them to accept a new commercial fishing venture. The venture, coming after scientific studies had estimated the amount of fish stock in the lake, proposed entry for large industrial fisheries that could remove dozens of tonnes of fish at a time – this whilst the community members themselves are legally prohibited from any sale whatsoever.

Sorayda Cruz Vesada. Shipibo community member of the village of Caimito in Lake Imiria, affected by the indiscriminate application of state conservation laws

“We aren’t allowed to sell even one fish,” said Sorayda Cruz Vesada. She had been stopped by the officials for trying to sell a paiche (a large local fish) in order to be able to pay for the medications of her son. She was fined 1500 soles (approx $400) in a cash poor economy where there is not even a few soles for medication. In addition, she has a pending jail sentence of 2 years. Hers is not the only such story. It is this sort of pattern of inequality and injustice that has built up anger. No surprise then that the President of the Guardia, Marco Tullio, and community leaders consider the conservation area as a green extraction operation, protected by the law and the police – reflecting a more widespread international pattern that more recently has gone under new names like ‘green grabbing’. Leaders here think of conservation as a mask. All around the conservation area the government leases out large parcels of rainforest as legal concessions to large lumber companies. The largest amount of illegal logging and coca plantations end up on these concession lands, but nobody seems to want to do anything about that.

Instead, the regional government, USAID, and local NGOs keep their sights on the pristine lagoon and surrounding forests. As is often the case, this summer they began to prepare for their proposal by creating local interest groups. They began by forming fishing groups within the Imiria area, which would be given permits to fish commercially, as well as training and some tools. But it felt like fishbones compared to what was being offered to the commercial fisheries. And it was understood as a common ruse that the State-NGO complex has often been used to break the unity of communities, by promoting the interests of a few. When representatives of the state, NGOs, and USAID landed on the shores of Caimito they were surprised to be met by a line of authorities and protestors, including children holding up signs, who were there to reject them. Somewhat baffled, they turned to slip back into their boats and motor off. With the action, the communities presented a list of demands and solutions: following a legal exit from the Conservation Area decreed by the state in 2010, they propose to form their own Indigenous Ecological Area to better manage the resources and their own territory.

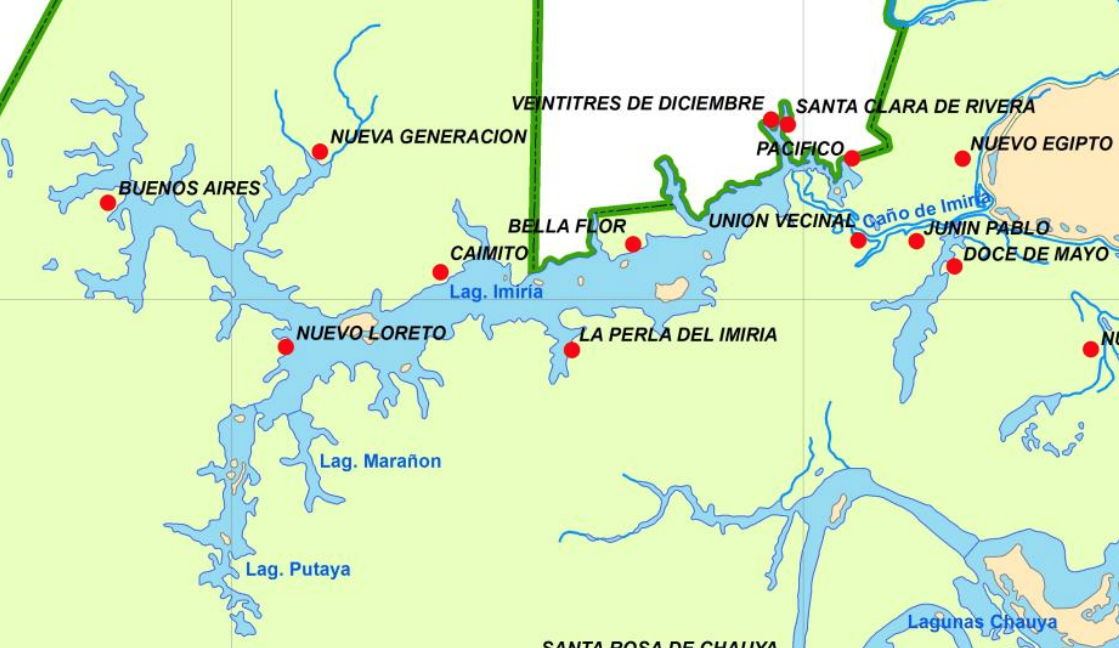

The Lake Imiria archipelago is one of the 75 Protected Areas in Peru. This is also the ancestral home of Shipibo Amazonian Peoples.

Several such initiatives for Indigenous ecological zones have met with some success in the last two years. This past summer, the Mamalilikulla First Nation in Canada declared part of its traditional coastal territory to be an Indigenous protected and conserved area (IPCA) in order to prevent logging and over-fishing. In Peru, the Wampi nation has previously advanced a model of autonomous governance over the conservation of natural resources. The Reserva Comunal (“communal reserve”) Tuntanain created in 1999 is still a reference to an enacted customary law and policy framework that aligns with Shipibo claims in the Imiria Lagoon. In fact, years prior to the formation of the ACR, as commercial extraction of lake resources was beginning to build during the neoliberal Fujimori era, the communities of Imiria had come together to form a communally managed reserve. Laureano Ancon, one of the community elders and leaders at the time of the “toma”, recounted how they organized to stop fishing boats from entering and extracting. “In little time, the fish population grew,” he said. “We know how to manage our resources.” Although he adds that the younger generation needs to still learn that properly. Community members who we interviewed expressed complete awareness of how the games of the government and NGOs, funded by USAID, continue day in and out affecting their lives on a daily basis. Laureano and the new Shipibo generation from Lake Imiria know that after years of inaction, suddenly new political campaigns and changes have left them in limbo.

Map of the Indigenous and Campesino communities and settlements around Lake Imiria. (Source: Master Plan of the Regional Conservation Area ACR Lake Imiria - Plan Maestro del Área de Conservación Regional Imiría. Copyrights 2014 Gobierno Regional de Ucayali.

While NGOs supported by USAID have started to send sewing machines and fishing nets to the communities, the appointed Peruvian Ministers of Environment and Agriculture and Irrigation have been dismissed by congress and changed for new administrations in less than five months. In the back, the conservation lobby machines even have invited members of the Guardia to fancy hotels and, according to some reports, even offered money to drop the resistance. However, it seems that this is a new time. COSHICOX and a new consolidated representation of Indigenous Amazonian Peoples and Campesino communities are calling for USAID, which funds the largest umbrella Indigenous organization in South America, COICA, to stop facilitating the corruption of the regional government, and open a new formal process of prior consent process towards the creation of an Indigenous-led Communal Reserve that replaces a Regional Conservation Area with a majority of Indigenous Peoples' participation. This time, the enforcement of global treaties around Indigenous Peoples, biodiversity, and climate change in the region requires responsible cooperation and respect of the Peruvian government to its obligations and leadership toward the full implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

--Abou Farman is Associate Professor of Anthropology at The New School for Social Research. Reynaldo Morales is Assistant Professor at Medill School of Journalism and Media, Northwestern University and a Faculty Fellow at Buffett Institute for Global Affairs.