By Chad Valdez (Diné)

It’s 2010, late into the night, and the television screen is illuminating my best friend and me. We’re armed with Arizona teas, Hot Cheetos, and Xbox 360 controllers. On-screen, our characters are geared up with sci-fi armor and chainsaws attached to rifles. We settle in and load up a multiplayer game of "Gears of War 2" to play deathmatches through the night and into the next morning. While it was just the two of us in the room, we were never alone– Tai Kaliso was always there as well. With his mohawk, facial tattoos, heavy accent, and dark brown skin, there was another Indigenous person in the room, only he shined bright through the pixelated screen of the television, and when he died, he would always return. We never really thought about why we chose Tai as our character most nights. The easy answer was that we thought he was the coolest, the most badass character there was. If we gave it some more thought, however, I’m sure the real reason was because he reminded us of ourselves. We saw someone that sort of looked like us, or at the least, had skin like us (we were lacking the muscles and tattoos back then) and talked with an accent we may have heard from family members, always wanting to share some wisdom in a story or through some strange humor. “Embrace what you can’t change,” he once said after being stuck in a vehicle with a bad driver. With him, we had representation.

Representation for Indigenous Peoples in video games has a sordid history. Even before video games, the representation of Indigenous Peoples in media was in a sorry state. We were the enemies for the cowboys, the shamans for the heroes, the burial grounds for the ghosts, the savage Indian to be saved. When video games were first being developed, the roles of those cowboys and heroes shifted into the hands of anyone in the world with access to an arcade or gaming system. But for Indigenous Peoples, we were still the enemies.

Image of gameplay from “Oregon Trail.”

After the ever-popular Pong took the world by storm in the early 1970s, video games evolved and grew into a wide array of stories, characters, and entertainment that anybody could pick up and play. And of course, the whitewashed history of America and the colonization of the West clawed its way into the new medium. Arcade games with stereotypes of Indigenous Peoples ran rampant. Again, we were the enemies to shoot, but this time, it wasn’t an actor doing the shooting, it was anybody who walked into an arcade with some change or a kid with a gaming system at home. Or it came preloaded onto computers with the label “educational” and the title "The Oregon Trail."

"The Oregon Trail" was first made in 1971 but it was the later version of it in 1985 where its popularity grew. Even today, people still quote the infamous term from the game “You have died of dysentery.” Players take on the role of a wagon leader guiding settlers to Oregon in 1848. While traveling, players must make decisions that ensure the survival of the group. Players decide what supplies to bring along, the route to travel, and actions during random events that can occur such as storms or disease. A memorable event that can happen during gameplay is attacks by “Indians” that kill members of your traveling party. Portrayals of Indigenous Peoples relied on tropes and stereotypes, common to what people were used to seeing in older arcade games. War paint, feathers, bows and arrows, and large noses, were the prevalent features of Native Americans in media. Because of the popularity of the game and the assumed historical accuracy of European settlement, it was soon considered an educational tool that could be played in classrooms, or at home, as some computers even came preloaded with it.

The depictions in "The Oregon Trail" reflected common perspectives of Indigenous Peoples, but luckily, this would change with time. The legacy of "The Oregon Trail," and the evolving perspectives of Indigenous Peoples, are marked by its most recent remake, 2021’s release on Apple Arcade. This version is a reiteration developed alongside Native American historians who lend their perspectives and insight into the improvement of the game so it is done with better accuracy. When starting this new version players begin with an image of an animated authentic depiction of an Indigenous woman and a recognition that westward expansion was not an adventure for Indigenous Peoples, but an invasion. Playable characters now include Native Americans that are not pan-Indian designs. This updated version of "The Oregon Trail" reflects not only an evolved game but a display of how far the industry has come to now including Indigenous Peoples in the making of these games. What was once just another game that viewed Indigenous Peoples as part of history and as a stereotype, has now evolved into something better. While "The Oregon Trail" was gaining popularity as an educational game throughout the 1990s, another not-so-much educational game was gaining a reputation as being one of the greatest ever created.

"Doom," released in 1993, took over the gaming world. Considered the “father” of the first-person shooter, a genre of gaming that is still one of the most popular today, it was and is arguably one of the most important games ever made. Players take on the role of a space marine fighting the undead and demons on the moons of Mars. But it was the gameplay that made it so influential. "Doom" puts the player directly in the perspective of this character, we saw through their eyes, the weapon was in our hands, and we had control of what to do completely in a new 3D setting. It also was when the term “deathmatch” was coined. These were multiplayer matches where players could compete against friends to see who would come out the winner. Behind the game, the designer’s story was just as interesting. Designer and co-founder John Romero is part of the Yaqui and Cherokee Nations. Romero and his parents moved from Arizona to California when he was young so was not involved with many aspects of his heritage at that time. It wasn’t until later in life and after the success of "Doom" that he began the process of reconnecting with his family outside of California and better understood the culture he was part of. After embracing his Indigeneity and relatives, he established himself as a strong inspiration for Indigenous developers and players, helping to uplift their voices even more. He represented what was possible.

Indigenous Peoples like to find Indigenity in characters and media that are not inherently Indigenous. Take, for example, the 1987 movie "Predator." While not obviously Indigenous (except for Sonny Landham’s role as the Native American character Billy Sole), Native American communities latched onto that movie and viewed it as ours. So much so that the latest in the "Predator" movie series, 2022's "Prey," has a titular Comanche woman fighting and defeating the alien predator. I would argue the same thing happened with "Doom." Indigenous gamers played this game and knew something about it felt Indigenous. Maybe it was the stereotypical stoic character or the non-linear nature of it all, but whatever it was, there was a feeling like one of our hands helped shape it. And because of that first-person perspective, anyone could have been behind that helmet. Luckily, John Romero was there, and is still here, helping and inspiring Indigenous game developers to get their footing in that world.

Image depicting Tommy from “Prey."

After all the stereotypes and harmful depictions of the late 20th century, some developers realized the error of their ways and planned to produce a game that was not entirely based on tropes and seeing Indigenous characters as historical figures. Enter "Prey" (unrelated to the 2022 movie), which was released in 2006. This first-person shooter focuses on the Cherokee character, Domasi “Tommy” Tawodi who, with his girlfriend and grandfather is abducted by aliens on their reservation in Oklahoma. The character is voiced by acclaimed actor Michael Greyeyes, a member of the Plains Cree from the Muskeg Lake First Nation. While still featuring some common tropes, such as Tommy entering the spirit world and having special abilities because of it, the creators behind the game did not want to do a pan-Indian stereotype, instead wanting to show life for Tommy on the reservation in contemporary times. They also welcomed the critiques from Micheal Greyeyes who gave extensive notes on the character and how he should best be portrayed. Greyeyes had the freedom to play Tommy as he saw fit and without any stereotypes involved.

Image depicting Ratonhnhaké:ton/ Connor from “Assassins Creed 3.”

When asking someone who plays video games to name one that’s about Indigenous Peoples with an Indigenous character, chances are they will say "Assassins Creed 3." Released in 2012, this game had a massive budget from an impressive game publisher and development company called Ubisoft. The third game in a large franchise, it’s an action-adventure that spans a large landscape filled with hundreds of characters players can interact with. The series emphasizes the accuracy of its historical settings and people of the time. "Assassins Creed 3" focuses on 18th-century Colonial America from 1754 to 1783, with a protagonist named Ratonhnhaké:ton/Connor, a Mohawk man who becomes an Assassin to protect his people. Ubisoft set out to create this game properly. Featuring Indigenous actors for the Indigenous characters, and Mohawk consultants alongside the making of the game, they knew how easy it was for their mostly white team to fall into creating stereotypes. “...We’re very aware that we’re still pretty much a bunch of early-middle-aged white guys.” Alex Hutchinson, the creative director, said in an interview. “We didn’t want to make mistakes, even well-intentioned mistakes.” Understanding their own limitations in the making of this game, the team hired Thomas Deer from the Kanien’kehá:ka Onkwawén:na Raotitióhkwa Language and Cultural Center to help not write Ratonhnhaké:ton into a stereotype and instead give him a fully fleshed-out character background. The team also worked with the Kahnawà:ke Mohawk community to ensure the accuracy of the character, even hiring some of the residents to translate, voice act, and sing in the game. "Assassins Creed 3" became an example of how to create Indigenous characters with respect and with Indigenous People involved.

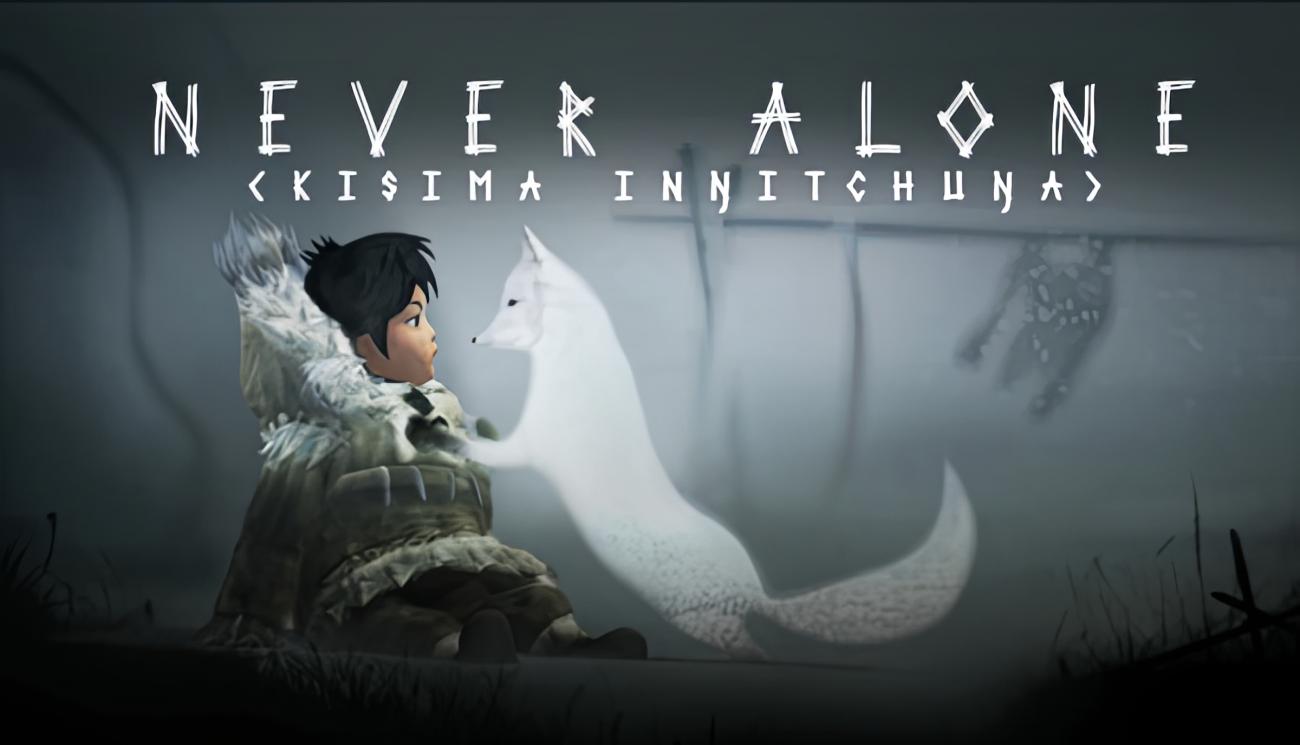

For an educational and entertaining game worth playing, with cultural aspects done completely right, "Never Alone (Kisima Innitchuna)" is the game that shines. It is a puzzle platform game produced, written, voice acted, and featuring, Indigenous Peoples, specifically the Iñupiaq Peoples in Alaska. With the idea stemming from the Cook Inlet Tribal Council of how best to showcase their culture, and deciding on video games, this is the story of a traditional Iñupiaq tale and is narrated by their people in their language. Players take control of an Iñupiaq girl and her arctic fox, playing through the traditional story to help her people. While going through the game, players collect “cultural insights”, which show documentary videos of the Iñupiak people telling stories and sharing their people's and culture's wisdom. Those involved with the development of the game recognized that video games were growing in popularity, especially among younger children. This game, and many Indigenous games, moved past the idea of them being simply for entertainment. They became educational, vehicles for knowledge of a culture. And it worked. The game has millions of downloads, has won multiple awards, is discussed in university classrooms, and is played in public elementary schools around the world with teaching guidelines. The influence of this game reaches far, and shows what is possible when video games are done correctly, when they are not simply about Indigenous Peoples, but are made by them.

Elizabeth LaPensée is an award-winning designer, writer, and artist who uses her knowledge as an Anishinaabe and Métis person to create video games for Indigenous Peoples. "When Rivers Were Trails," created by LaPensée, is a stunning adventure game where players journey through different areas in the past and learn about the land and the effects of colonization from indigenous wisdom and insight. Her other game, "Thunderbird Strike," has players take control of a thunderbird protecting Turtle Island from the oil industry. Not only are these games amazing in their gameplay, but they also have the dual purpose of teaching in them. She is still doing amazing work today, working as Narrative Director for Twin Suns, a global video game studio.

Ashlee Bird, a member of the Western Abenaki, is an assistant professor of American Studies at Notre Dame and game designer whose research focuses on Indigenous video games. Her work in Native American studies and gaming theory aims to shift the nature of video games and decolonize them in numerous ways. To change the way games are colonial in nature, her games, "One Small Step," and "Full of Birds," do not focus on collecting money or fighting enemies like other games do. Instead, they are full of messages of what colonization has looked like, and the beauty in Indigenous art.

These are just some games and developers/creators making incredible Indigenous video games today. There are many more out there, sharing cultural wisdom, portraying Indigenous characters with respect, and representing for a young kid picking up a controller or keyboard and mouse. They are not just showing Indigenous Peoples in the past as history, or as enemies, they are showing contemporary living and a character whose entire identity isn’t simply “Indian.” These are the games worth playing, alone and with friends. Video games invite players to experience new and diverse stories, and have interactive experiences where players can be in control of something new. Simple representation is not the end goal, however. Indigenous Peoples can and should be involved in the creation of the game. We cannot only watch and play from outside the room but must place ourselves inside at the table.

The amazing work being done today by Indigenous developers, creators, and writers needs to be noticed. We’ve seen examples of what can happen when Indigenous Peoples are involved with media about them. "Reservation Dogs" is considered one of, if not the best television series of the past few years, and has won multiple awards. Lily Gladstone made history by being the first Native American woman to win Best Actress. "Never Alone" is displayed in museums across the country and is used as a teaching curriculum across the world. Indigenous stories are special. They are important.

I still play games with my childhood friend. Nowadays, we can’t stay up as late anymore, we have work in the morning, he has a baby to take care of, and there’s usually something keeping us from being able to hop into a game, but we still do our best to find time to play a quick match of something together. Lately, it’s been "Call of Duty." And while there are so many interesting characters and skins to choose from, I still like Talon, a First Nations character available to play as. Like most other skins we can pick from, there isn’t a real background story or details to the character. They’re just another in a vast collection of skins we can choose from. But when we play, we can see ourselves up there on the screen again, an Indigenous character being controlled by two chi’zhii kids.

--Chad Valdez (Diné) is a 2023–2024 Cultural Survival Indigenous Writer in Residence.

Top image: Cover image of “Never Alone (Kisima Ingitchuna)."