Shocking images have been released over the past few days showing the suffering of Yanomami Peoples in the Brazilian and Venezuelan Amazon. In the third week of January 2023, Yanomami people in Roraima, northern Brazil, were found with severe malnutrition, especially in children. According to the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, nearly 100 children between the ages of 1 and 4 died in 2022 from malnutrition, malaria, pneumonia, and diarrhea. It is estimated that hundreds more have died in recent years from the same problems, and also at the hands of criminal groups operating on Indigenous lands.

At the beginning of former President Jair Bolsonaro’s reign, numerous Indigenous rights organizations such as Articulação dos Povos Indígenas do Brasil and Cultural Survival informed the Brazilian government about the dire situation of the communities in the region and pushed for urgent action. However, Bolsonaro’s anti-Indigenous agenda ignored and actively worsened the situation by withdrawing federal environmental police from the area, relaxing environmental laws (which facilitated the advance of illegal mining in the region), and dismantling public policies for Indigenous Peoples. The Yanomami situation is shocking and criminal in many humanitarian, moral, and legal aspects.

Map of Yanomami lands by Wikipedia

How to Create an Ecological Catastrophe

The territory of the Yanomami Peoples has been the target of illegal mining since the 1970s. Legal and illegal extractivist activities seek cassiterite, gold, and other ores. Because of this mining activity, the Yanomami, like many other Indigenous Peoples in the region, are exposed to pollution, especially mercury, created by the actions of the land invaders. The negative impact is significant on the rivers, animal, and plant life, as Cultural Survival detailed in a previous article. Several studies show devastating contamination of fish and water causing environmental damage, loss, and risk of extinction of species. The most affected rivers are the Uraricoera, Parima, Igarapé Inajá, Igarapé Surucucus, Mucajaí, Couto Magalhães, Apiaú, Novo, and Catrimani, all of which are essential sources of food for Yanomami and Indigenous Peoples and carry cultural and biological significance.

In the four years of Bolsonaro’s government, at least 570 Yanomami children died, mostly from hunger or curable diseases. These numbers may be even higher due to an intentional blackout of the health data about Indigenous Peoples during this time. This lack of data is part of the complaint filed by many organizations at the International Criminal Court accusing Bolsonaro of genocide of Indigenous Peoples.

The incomplete health reports from January 2023 are frightening; 11,530 cases of malaria have been confirmed in just this month alone. The most affected age groups are those over 50, followed by 18-49 and 5-11. At least 80 percent of children from isolated communities and children across the Yanomami Territories are underweight. Death and other sickening conditions from malnutrition have become more frequent. Last week, the image of a Yanomami woman who died was widely shared on social media by public agents in an act of disrespect toward communities. In the Yanomami worldview, showing images or even an object of a deceased person is considered deeply disrespectful to their spirits; the deceased person’s name also cannot be mentioned, according to her people.

Since 2018, local leaders have filed more than 100 requests for help from the federal government and Indigenous health protection agencies. The requests were ignored, demonstrating clear abandonment by the State. By 2020, mining and deforestation on Yanomami, Munduruku, and Kayapo lands increased 30 percent, one of the sharpest increases in history. In 2021, more than 20,000 illegal prospectors invaded the Yanomami territory.

Lobbyists representing corporations with extractive interests also grew exponentially under Bolsonaro. In November 2022, when the former Secretary of Indigenous Healthcare, appointed by Bolsonaro, was asked about the situation of the Yanomami, he answered: "their health is wonderful." According to an investigator from the Federal Public Ministry, the same secretariat hid data and omitted information about the Yanomami. The situation has escalated since mining corporations primarily from Canada, the United Kingdom, and Norway have increased their presence in the region, bringing crowds of people seeking gold or job opportunities.

Garimpo, or wildcat gold mining, was also publicly promoted by Bolsonaro. (Rogue and illegal miners are called garimpeiros.) In 2021 in an informal TV interview, Bolsonaro said that his father was a garimpeiro, and “any Brazilian has the right to be as well.” Those words triggered an unprecedented invasion of garimpeiros, especially in Yanomami, Munduruku, and Kayapó lands. On Yanomami reservation land in the Amazon rainforest, land grabbing increased by 46 percent in 2021 to 8,085 acres. In the past year, some 40 to 80 small planes and helicopters have been circulating in Indigenous territories daily, carrying prospectors and tons of gold.

Mining destroyed a record 125 square kilometers of the Brazilian Amazon last year, according to data from Superintendência de Desenvolvimento da Amazônia Legal (SUDAM - Amazonia Legal Institute). In other river areas where hydroelectric dams, such as Belo Monte, were built, a legacy of social problems were left behind; because those projects do not bring development or welfare for the thousands of workers and communities in the region, when the projects end, many are left unemployed, houseless, and without money or care. This dark scenario creates an opportunity for drug lords and other facções criminosas (criminal groups) to take over the wildcat mining activities. Extractive activities are well known in Brazil for bringing violence, sexual harassment, drugs, fear, and terror to Indigenous communities. The State’s abject failure to protect Indigenous rights has contributed to the increase of murders of Indigenous Peoples and the destruction of the environment.

A recent report by the Federal Police shows that military personnel, government agents, and even FUNAI were corrupted by illegal miners in a murderous and genocidal corruption scheme. On June 5, 2022, Brazilian activist Bruno Pereira and British journalist Dom Phillips were murdered during a boat trip through the Vale do Javari, the second largest Indigenous area in Brazil, while conducting an investigation requested by Indigenous communities to broadcast their situation and denounce the threats they were suffering.

Even though State and corporate projects in the region, like dams and mining, have been an ongoing activity in the Amazon, never before has it taken place with such intensity and acceleration. In the last five years under Bolsonaro, there was a clear agenda for deforestation, mining, and exploitation of the ecosystem in detriment to so many Indigenous Peoples.

Yanomami children receiving food relief from SESAI team in 2023. Photo courtesy of SESAI.

Necropolitics

The Yanomami humanitarian catastrophe is one of the many horrifying examples of Bolsonaro’s necropolitics, a term coined by the African historian Achille Mbembe to describe the use of political power to replace life for death or to subjugate lives to austerity, immiseration, merciless exploitation of the ecosystem, and eventually death. The Federal Public Ministry, together with the newly created Indigenous Peoples Ministry, recently issued a report denouncing Bolsonaro's public policies and environmental protection bills that were blatantly incompetent and designed to fail. As one example, the report shows that 400 illegal mining points were found in the Yanomami region as a result of an investigation by the federal police together with Indigenous Peoples. The officials responsible for monitoring the area only checked nine of these points in a short period of time, which is not considered standard or acceptable by the mining and environmental monitoring agency itself.

The report also shows that Bolsonaro pressed for numerous bills to legalize mining on Indigenous lands. Starting in 1992, when he was still a congressman, Bolsonaro proposed a bill to clear the Yanomami lands and remove Indigenous Peoples from their homelands. It is important to note that mining is forbidden on Indigenous lands by the Constitution. The proposed legislative changes spurred protests from Indigenous and environmentalist organizations.

In 2020, numerous organizations from all over the world wrote letters to Bolsonaro denouncing the health crisis and lack of security for Indigenous Peoples in the country. Cultural Survival's letter received an official response saying they were being taken care of, but there were no details of the actions to ensure the physical integrity of vulnerable populations. No further communication was received.

Cultural Survival and other organizations continue to find it difficult to contact and support many Indigenous communities in Brazil because of State mismanagement, bureaucracy, unexplained slowness in banking transactions, and lack of internet access in the communities, among other factors. NGOs in Brazil similarly have faced many difficulties in raising funds and visiting Indigenous communities, particularly since Bolsonaro took office in 2019. Armed criminal groups that set up camp around Indigenous lands have posed an additional risk not only to Indigenous Peoples but to anyone else who attempts to visit the areas.

The Amazon rainforest has been breached and destroyed for years. Studies show that it takes a long time for biomes to recover, and some parts of the Amazon might never regenerate or recover. The environment in Brazil is extremely diverse and rich, and the complexity of any action to undo the damage is immeasurable. Areas that were mined in the 1960s and ‘70s have not yet recovered—not even the riparian forest along the rivers, despite the work of Indigenous and environmental organizations. The rivers are contaminated, increasing the crisis not only for the Indigenous people living in the forests, but for entire local communities and neighboring towns that live in the area.

A Ground for Hope

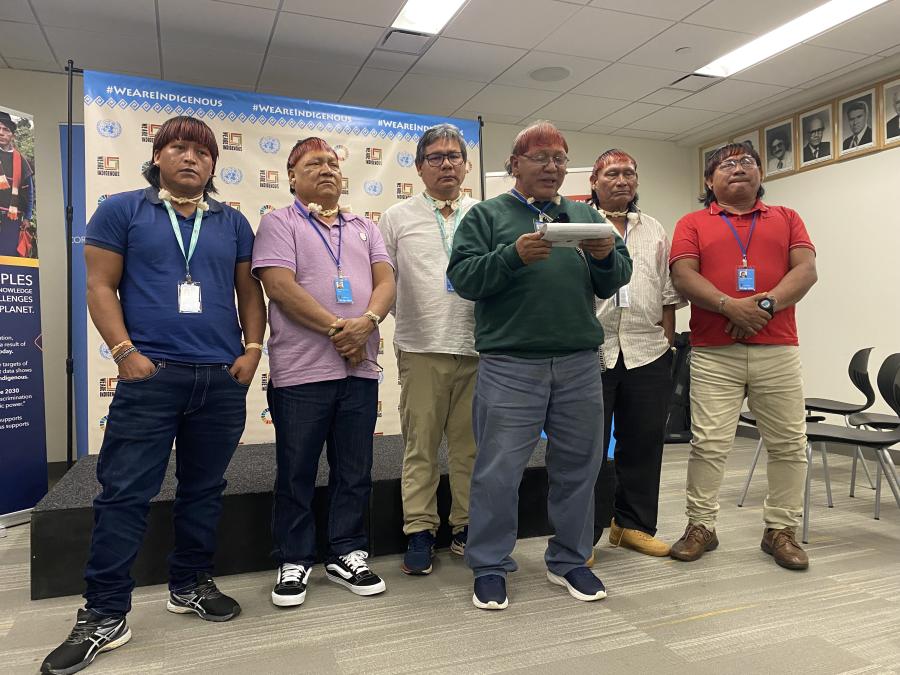

Weibe Tapeba (Tapeba), Chief of SESAI. Photo courtesy of SESAI.

Cultural Survival recently spoke to the country's new chief of the Special Health Secretariat for Indigenous Peoples (SESAI) and secretary for Weibe Tapeba Indigenous Peoples, a Keepers of the Earth Fund grant partner in Brazil. He said that when he arrived in Yanomami territory, it looked like a “concentration camp, a war zone. Bolsonaro and the Brazilian State completely abandoned these people. I'm terrified,” he said. The new chief, along with the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, is concentrating all efforts and resources to serve the Yanomami. Several villages will have to be relocated to areas where there is food, safety, and clean water.

Due to the complexity of the situation, the size of the territory, and the resources available, the Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon need international support. Those behind this unprecedented humanitarian crisis have to be held accountable, including large corporations.

Cultural Survival has recommended to international human rights bodies such as the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination that Bolsonaro and his administration must be held accountable for what happened to the Yanomami and other Indigenous Peoples in the country, as well as for the pollution of rivers and forests. It is beyond genocide: it is ecocide. Cultural Survival urges Karim Khan, chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, to consider the international petition from Indigenous Peoples’ organizations to investigate and punish Bolsonaro for his crimes. It will bring justice for centuries of violence and violations of human rights committed against Indigenous Peoples.

Many European Union countries, the United Kingdom, China, Canada, and the United States have financed this ecocide by purchasing wood, importing gold, extracting other metals, and trafficking numerous of the region's animal species. The Yanomami humanitarian crisis is a catastrophe that impacts the forest, the planet, and threatens the lives of all of us.

Top photo: Photo courtesy of SESAI - Yanomami children receiving aid from FUNAI and SESAI