By Octaviana Trujillo, Laurie Smith Monti, and Gary Paul Nabhan

This last year, we have palpably felt a heightened level of traumatic stress pervasive in the Indigenous communities where all three of us have worked on both sides of the international boundary. Throughout our adult lives, we have provided educational opportunities, technical assistance, and land rights advocacy strategies within the many Indigenous communities that live within 100 miles or so from the U.S.-Mexico border. But now, we see the bridges that we have worked to build across the border threatened. Within the last year, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security began to build Trump’s 30 foot wall through many sacred sites and across many traditional pilgrimage routes that have served transborder Tribes for centuries.

Some of these routes once led to rare sacred springs, salt-gathering flats, ceremonial grounds and cemeteries. A few of those sites literally occur right on the border, on the very right of way that Homeland Security has begun to bulldoze to stage its construction of a thirty foot tall steel wall with 24/7 flood lighting on top. We are among the many activists who are bearing witness to the damage U.S. federal agencies do to culturally-important desert gathering grounds, mountain retreats, and oases, as they leave the smell of dead and rotting plants in their wake.

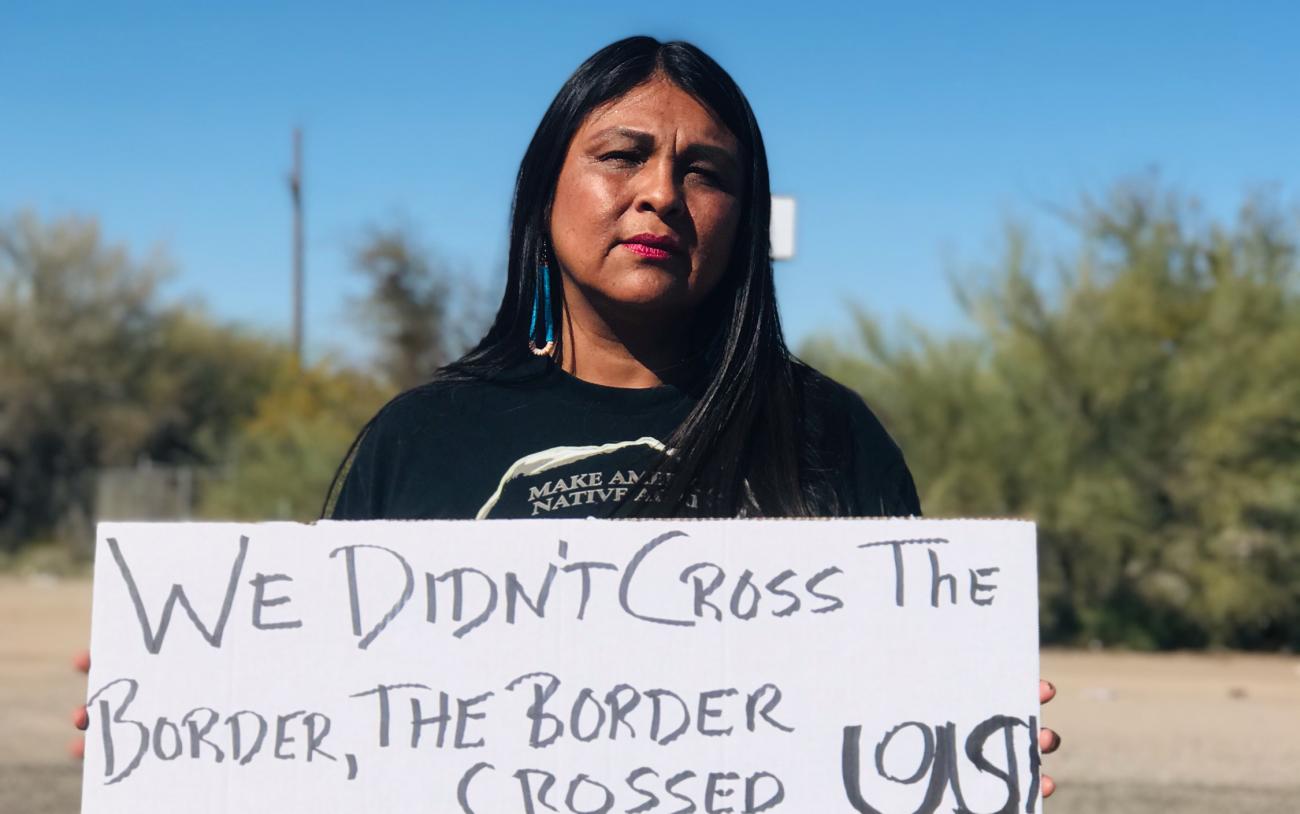

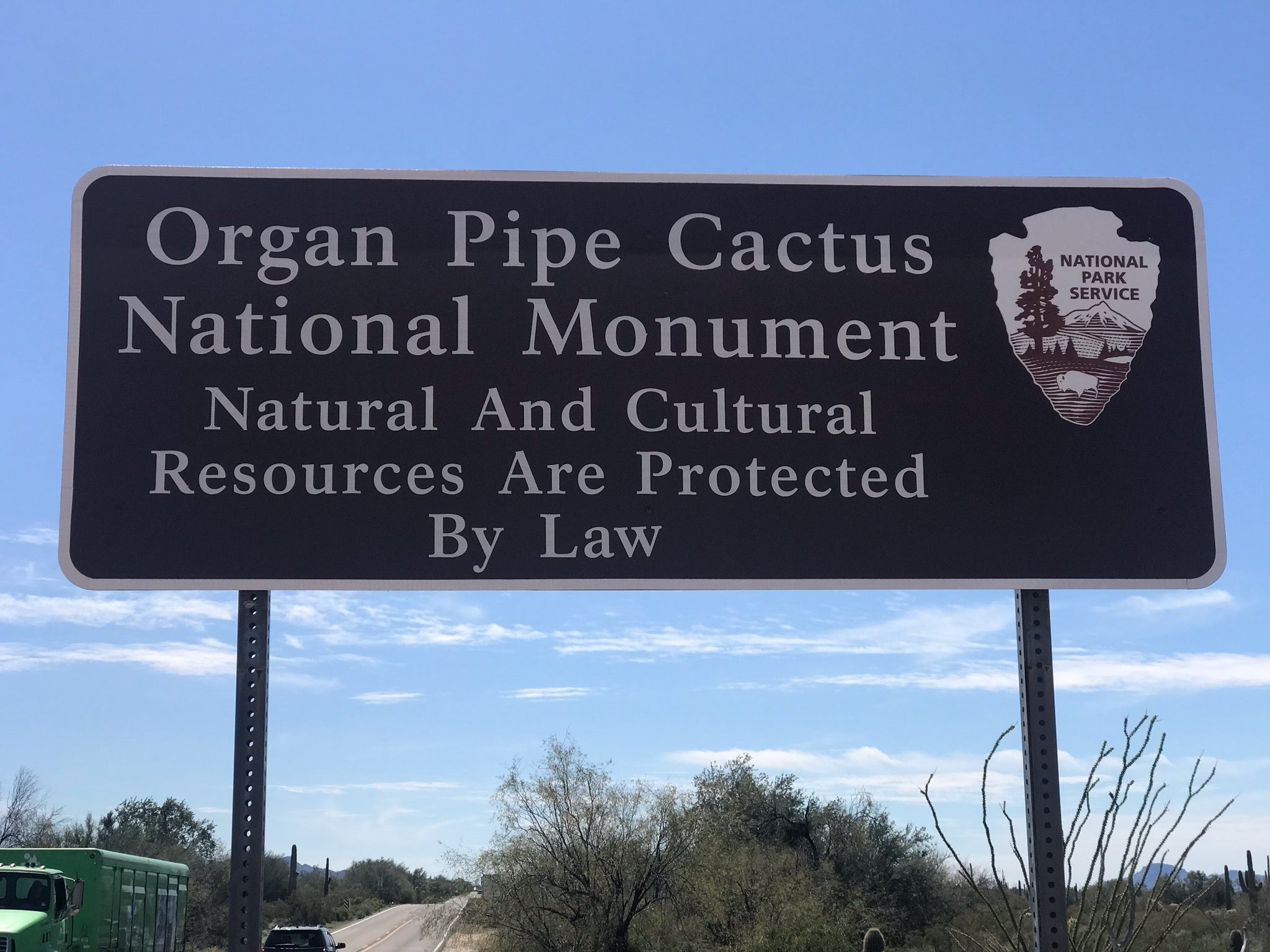

No wonder we sense so much stress, remorse and grief being expressed by our compadres and neighbors with deep cultural ties to these sacred sites. In December 2019, we joined in as speakers at a multicultural rally not far from wall construction sites in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Theis “Wilderness Area” lies just west of the Tohono O’odham Reservation, but has been part of O’odham homelands for millennia. We arrived within a few days of when Homeland Security began toppling hundreds of tall saguaro cacti that would be otherwise protected by Arizona State Native Plant Laws. Since 1937, the National Park Service has respected the O’odham community’s rights to gather cactus fruit at these sites, rights guaranteed by a Presidential Proclamation and the monument’s own enabling legislation passed by Congress.

We watched tearfully as two middle-aged O’odham women walked among the carnage of dozens of the sacred cactus plants whose fruits are required to ferment the sacramental wine used in their summer rain-making ceremonies. One of the women was weeping inconsolably. The other simply mourned a loud, “Why would anyone do this? What would make them do such a thing? Don’t they know that these plants are our ancestors?”

This is not the first or only episode of racism, resource usurpment, and violence against Indigenous border-dwellers and their traditions that has occurred since 1918, when a Yaqui youth became the first border-crosser to be shot and killed by U.S. law enforcers stationed on the border. The killing occurred at Nogales, Arizona, not far from where the three of us live today. The only error made by that Indigenous victim was trying to cross the border to see relatives that had settled on the other side. He apparently did not understand enough Spanish or English to comprehend an infantryman’s warning not to cross the open border at International Street in Nogales.

Today, Yaqui elders from the sacred Yoemem Pueblos to the south of the border are faced with a new wave of difficulties getting into the U.S., to guide their sister communities north of the border in their Lenten observances. These observances keep alive centuries-old folk Catholic traditions of the Yoemem, but also include millennia-old sacred Deer Dance and Pascola traditions. Without the spiritual leadership of these maestros from the Rio Yaqui communities in Sonora to guide the ceremonies held today in Yaqui barrios within Tucson and Phoenix, these ancient traditions can be disrupted or diminished.

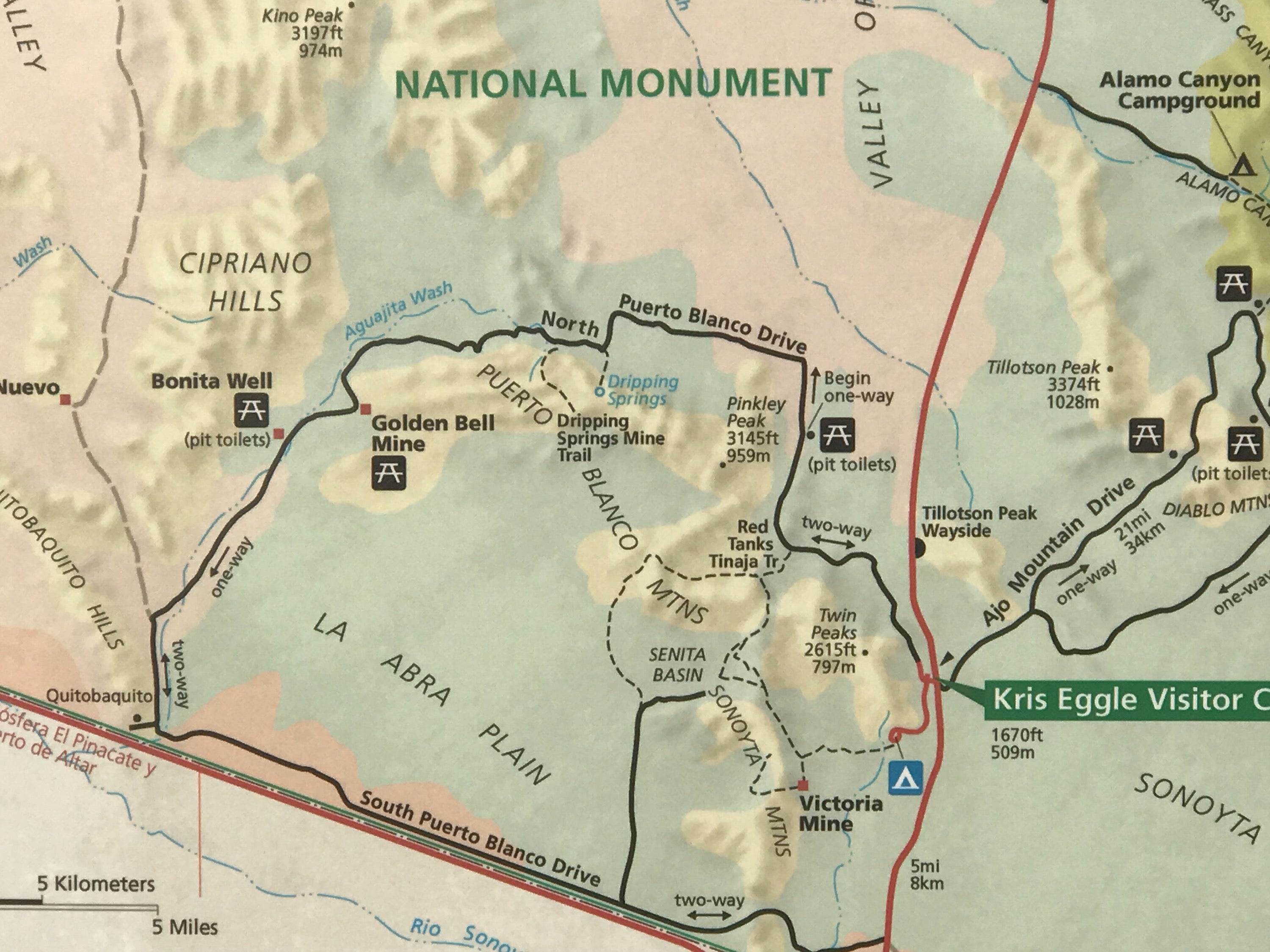

We have also engaged in dialogues with O’odham communities on both sides of the border, for we have historically documented their spiritual traditions that are being directly violated and disrupted by Trump’s border wall construction. There are both Tohono O’odham and Hia c-ed O’odham families who live immediately adjacent to the international boundary, in villages on both sides of the border barriers. They are subjects of frequent harassment by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents. Many of the families’ transborder cultural practices are now difficult to maintain due to changing policies and unprecedented barriers. Tohono O’odham and Hia c-ed O’odham have lived and maintained ancient spiritual practices for centuries at Quitobaquito, a spring-fed water hole on the border roughly 100 miles west of Nogales and 50 miles northeast of one of their places of origin. As Verlon Jose, governor and spokesperson for the traditional O’odham leaders of Mexico has stated, “The new border wall would cut off the route of ceremonial salt pilgrimage and interfere with this sacred ritual,” by blocking access to the sea shores edging the revered Sierra del Pinacate in Mexico. Quitobaquito is the closed sacred site and stopover with water on the way to this sacred mountain and its salt flats near the shores of the Sea of Cortez in Mexico.

While the O’odham still have strong ties to these sacred sites, they lost their property rights to their lands at Quitobaquito in the 1950’s, through a scandalous set of maneuvers by unscrupulous Park Service officials. Their eviction from Quitobaquito was ironic, for several decades before, the federal government itself had drawn up a map circumscribing a 200 acre area for an O’odham Reservation on the half of their village area north of the border. Later, the Park Service wanted to build a resort hotel there at one time, and so began humiliating the Native residents remaining in the area by posting roadside signs on the way to the springs that said, “Watch Out for Cattle, Deer and Indians.”

Although the O’odham never lived year-round at Quitobaquito after the 1950s, one of us witnessed tribal elders there in the 1970’s and 1980’s who regularly arrived for seasonal spiritual observances, including Day of the Dead ceremonies. By that time, many O’odham blended Catholic traditions with their own Indigenous spiritual traditions. Quitobaquito’s spring waters were used for baptisms as late as the 1980’s. Curiously, the first recorded Palm Sunday Mass in what is now Arizona occurred at the springs in 1698. That’s when the O’odham share palm fronds with Jesuit missionary Padre Eusebio Kino for a celebration at that sacred site. Such religious expressions have been practiced there ever since. Despite the fact that Quitobaquito Springs lies off reservation, all Park Service superintendents at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument have reaffirmed and even facilitated the O’odham Peoples’ right to continue to practice their spiritual traditions there.

It is only Homeland Security that insists that it has the authority to disrupt or diminish these time-tried traditions on the basis of a Presidential Proclamation of a “border crisis” in the summer of 2018. That so-called emergency has allowed Homeland Security to waive 41 different federal and state laws protecting antiquities, religious freedom, and endangered species protection in order to fast-track the building of the wall. In late January 2020, CBP Chief of the Tucson Sector, Ray Villareal, used those waivers as his excuse for allowing bulldozers to cut into burial sites, displace human bones, blow up a mountainside and topple cacti near Quitobaquito. In doing so, Villareal and his D.C. boss Paul Enriquez flagrantly violated another Presidential Proclamation, the 1937 declaration by Franklin Roosevelt guaranteeing the Tohono O’odham rights to resources in that landscape.

Nevertheless, Homeland Security did not and cannot waive the constitutionally-guaranteed expression of religious freedom that applies to native spirituality as well as to formal western and eastern religions. Although few cases advanced by Indigenous Peoples have been recognized by the high courts, we are among the many who believe that the O’odham practice of their place-based spiritual traditions fully meets protection criteria under the constitution.

When the three of us spearheaded “listening sessions” with over a dozen western tribes in order to develop a Sacred Lands and Gathering Grounds Tool Kit over a decade ago, we could not have realized that some of the legal principles elucidated in the Tool Kit would be needed to help protect Indigenous religious freedom in our own backyard. We urge all Tribes and their legal experts to join with the Alianza Indigena Sin Fronteras to challenge Homeland Security on its unnecessary, arrogant and illegal destruction of sacred sites, their associated waters and plants, and its disruption of cross-border exchanges among Indigenous spiritual leaders.

--Octaviana V. Trujillo (Yaqui), Ph.D., is founding chair and professor of the department of Applied Indigenous Studies at Northern Arizona University (NAU) and teaches courses on Tribal Nation Building. A primary focus of her work as a former vice-chair of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe has been developing programs that provide the use of her academic and human rights advocacy training to Indigenous communities in the U.S./Mexico border states. Trujillo is the co-director of the Center for American Indian Resilience (CAIR), and has served as an active national member of the American Friends Service Committee on Farmworker Justice, working to foster community-based resources for promoting social justice.

Laura Smith Monti (Italian-American) is affiliated with Prescott College, the Zuckerman School of Public Health and Southwest Center of the University of Arizona, and the Borderlands Restoration Network. A community health professional and cultural ecologist, she grew up in Colombia and worked as a program officer for the Christensen Fund in Mexico and the U.S. Southwest. She advocates for policies to ensure the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge of healing plants and landscapes to deal with the contemporary health issues facing tribal communities in Latin America and the U.S..

Gary Paul Nabhan (descended from the Banu Nebhani Tribe of the Arabian peninsula and Lebanon), PhD., is the Kellogg Endowed Chair for Borderland Food and Water Security at the University of Arizona. He is also an Ecumenical Franciscan Brother who is involved with the Franciscan Action Network on border justice and caring for creation. An intern at the first Earth Day’s HQ, Nabhan has written for Cultural Survival Quarterly, Orion, Earth Island Journal, Yes! and other magazines for over a quarter century.

All photos by Gary Paul Nabhan.