“After many years of paralysis of Indigenous land demarcation and rights violations (by former governments), we are now back to having our rights recognized, our lives valued, and our territories defined,” said Brazil’s first Indigenous State Minister, Sonia Guajajara, in a social media post.

A ceremony celebrating the demarcation of six Indigenous lands took place on the last day of the Acampamento Terra Livre (ATL)-Free Land Camp, the biggest Indigenous advocacy event in the country, on April 28, 2023. The newest demarcated lands are: Arara do Rio Amônia, land of the Arara Peoples; Kariri-Xocó Porto Real, land of the Kariri Xoco Peoples; Rio dos Indios, land of the Kaingang Peoples; Tremembé da Barra do Munda, land of the Tremembé Peoples; Avá-Canoeiro, land of the Kaingang Peoples; and Uneiuxi, land of the Maku and Tukano Peoples. Both the Kariri Xoco and the Tremembe Peoples are Cultural Survival Keepers of the Earth Fund grant partners.

Besides the homologation–or official recognition, certification, and final endorsement–of those lands, scaffolding policies were created to monitor, protect, recover, conserve, and use natural resources sustainably in those Indigenous territories. April 19, 2023, was also the first time that the federal government honored the Day of Indigenous Peoples as an official holiday, a victory for Indigenous Peoples.

The Demarcation Process in Brazil

The guarantee of the rights of Indigenous Peoples’ rights to the land is referred to in Brazil’s 1988 Constitution as the demarcation of Indigenous lands. It is extremely important for maintaining identity and livelihoods, preventing conflicts, and guaranteeing the rights of all first nations in the country.

By establishing the physical boundaries of an Indigenous Peoples’ land, the demarcation of territory ensures that Indigenous Peoples' land rights are recognized and protected. It establishes a legal framework that helps prevent land grabbing and other forms of exploitation of Indigenous lands and resources, promotes the protection of cultural heritage and the environment, seeks to improve health and well being, and ensures human rights in the country.

According to FUNAI, a Brazilian government agency dedicated to Indigenous Peoples, currently led by Joenia Wapichana (Wapixana) and a land management department of the National Indigenous Ministry, demarcation also helps to reduce conflicts over land ownership. It also enables states and municipalities to address the needs of Indigenous Peoples through particular policy initiatives, thereby enhancing the state’s ability to provide resources to vulnerable and difficult-to-access areas. As stated by FUNAI, securing the right to demarcation is a way to contribute to the creation of a "pluriethnic and multicultural society."

Demarcation is also a critical step to ensure the protection of the environment and biodiversity. According to some studies, Indigenous lands in Brazil have the potential to prevent the annual emission of over 31.8 million tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere (1, 2). As a result, by protecting the boundaries of Indigenous lands, land demarcation aids in the stewardship of the environment, maintenance of the climate, and climate change mitigation.

What Does Land Demarcation Look Like?

In Brazil, FUNAI oversees land demarcation, and the president oversees FUNAI’s work. According to FUNAI, the complicated stages of land demarcation are as follows:

- Identification and technical study: Anthropological, historical, cartographic, and environmental studies are conducted to provide a basis for identifying and defining an Indigenous area.

- Delimitation: The stage in which the studies have reached their conclusion and the FUNAI president has approved them for publication in the State's official journal.

- Declaration: Stage 1 and Stage 2 are reviewed by the Minister of Justice and the Minister of Indigenous Peoples. The Ministers will then make a decision and if they consider it appropriate, they will set the boundaries and determine the physical demarcation of the area subject to the demarcation procedure through an ordinance published in the Official Journal of the Brazilian Federative Republic.

- Ratification: Materials describing and formalizing the territory, such as maps and georeferenced boundaries, are published, and then, by Presidential Decree, designated as Indigenous Land (T.I., or Terra Indigena in Portuguese).

- Regularization: Documentation of land tenure is issued in accordance with the provisions of laws (such as Article 246, Section 2 of Law 6.015/73). FUNAI assists the State Property Agency, a kind of federal real estate agency, in completing the cartographic record of the area.

- Homologation: Titlement (permanent possession of the land in Brazilian law) and a ceremony is conducted by the Brazilian president, recognizing and issuing full rights in accordance with the constitution, which states: "The lands referred to in this [Constitutional] article are inalienable and nontransferable, and the rights [of Indigenous Peoples] over them are imprescriptible."

In exceptional cases, such as those involving irresolvable conflicts, the effects of large-scale investments, or the technical impossibility of recognizing historically occupied land, the FUNAI advocates for an alternative recognition of Indigenous communities' territorial rights in the form of an Indigenous reserve. In this scenario, the State may encourage the direct purchase, deed in lieu of foreclosure, or donation of the lands that will be used to create an Indigenous Reserve, or Indigenous land (Terra Indigena TI in Portuguese).

In the case of populations living in voluntary isolation, FUNAI uses the legal tool of restriction of use to protect Indigenous Peoples’ territories from outsiders. This involves amending several legal provisions, at the same time that the identification and delimitation of the area are being carried out with an eye to the physical integrity of these populations in the event of a conflict. This process has happened with the Pataxo Peoples of Bahia, where the State failed to protect the community (SEE here).

Current Scenario and Challenges

According to FUNAI and Instituto Socio Ambiental (ISA), there are approximately 490 fully recognized Indigenous Territories (not demarcated lands, but ratified by FUNAI reports, maps, and documents) in Brazil today, totaling about 107 million hectares (264,402,758 acres), or 12.6% of the country's landmass.

According to the ISA, at least 236 regions are in the process of applying for official designation as Indigenous Territories. Dinaman Tuxa, Executive Director of the Association of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB), highlights that recognition and demarcation of territories “is essential for conserving Indigenous culture and environmental biodiversity.”

Unfortunately, demarcation itself does not guarantee the safety of Indigenous Peoples. On November 15, 1991, Yanomami lands in the states of Roraima and Amazonas were demarcated. During that time, there were 11,000 gold and timber prospectors in the territory. In 2021, 30 years later and during a global pandemic, the number of invaders had increased to 20,000, and they continued spreading diseases, drugs, violence, and environmental destruction. (Read more here about the humanitarian crisis the Yanomami Peoples are facing).

In the same context of violence and threat, 13 Indigenous Peoples (SEE MAP) expected to have their lands demarcated at the beginning of 2023. However, only six got their lands fully homologated. Those 13 Indigenous Peoples have fought for decades against a hostile government and a huge opposition inside and outside their lands to arrive at the last stage of the process of demarcation. Now, eight of them are deeply disappointed because they will be forced to wait longer, suffer more conflicts, and experience more insecurity.

One of Pataxó Peoples’ lands, Pataxó Barra Velha or Aldeia Velha, is at the center of a long-running rights dispute between the Indigenous population and nearby landowners. The demarcation procedure has been indefinitely halted despite efforts by the Pataxó Barra Velha community to get legal acknowledgment of their property rights. The community has several pieces of evidence documenting their living there since the 16th century. The village is considered the “mother village” of the Pataxó People.

The opposition of regional landowners, monoculture, and real estate interests are some of the primary causes of the delay in the designation of the Pataxó Barra Velha area. These entities have long fought the acknowledgment of Indigenous land rights in Brazil and have used a variety of strategies, including legal challenges, lobbying, and even violence against Indigenous people, to postpone or prevent the demarcation of Indigenous territories.

As of 2023, the Pataxó people are facing a new wave of violence and orders to vacate their settlements after reclaiming a portion of their ancestral territory. During the ATL-Free Land Camp, they demanded a solution from the recently elected government led by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. They are watching to see if and how the new Indigenous Peoples’ Ministry can reduce violence, mitigate land conflicts, and demarcate their lands while standing up to powerful economic interests in the region, including state and local authorities who have been linked to recent murders and violence.

Without official demarcation, agriculture, ranching, eucalyptus, and real estate development continue to encroach on Pataxo and other Indigenous territories, which are in legal limbo. After two Indigenous youths were killed in early 2023, the new Indigenous Peoples’ Ministry established a crisis committee to help deal with the escalating violence, but Pataxó leaders say little has changed and they live in a state of constant threats and tension. During the ATL-Free Land Camp in April 2023, when the government announced the six demarcated new lands and the Pataxo community saw that their land was not on the list, they became disappointed and frustrated.

Besides the conflict in the territories, the legislative houses are insisting on proposing bills and law reforms that can harm Indigenous rights and the environment. A dangerous bill and constitutional implementation, marco temporal, are to be voted on in the Federal Court, which has the power to make this stage more strict and difficult for Indigenous Peoples. (Read more here.)

The Indigenous Peoples’ Ministry and movement will need more than patience to face the other challenges such as:

- Political resistance: Political opponents of Indigenous rights and environmental regulations in Brazil have voiced strong hostility to Sonia Guajajara, and other Indigenous leaders since the previous government of Jair Bolsonaro. Corporate interests and other strong forces may oppose the participation of Indigenous leaders in the government.

- Violence and threats: The new ministry and Indigenous leadership in the government did not stop retaliations and threats against them. Several communities are experiencing violence and bigger challenges. Numerous acts of violence, such as assassinations, assaults on land defenders, and intimidation strategies, have been committed recently against Indigenous leaders and communities. (According to a news outlet “the hotline of Brazil’s Ministry of Human Rights and Citizenship, Disque 100, registered 2,846 human rights violations against native people of a range of ethnic groups, a survey conducted from January to March this year shows.”)

- Limited resources: Indigenous communities in Brazil frequently lack the funds and resources necessary to sustain their organizations and advocacy activities. After more than four years of bills and policies that have dismantled the country's social welfare and programs for Indigenous Peoples during the Bolsonaro administration, the Indigenous Peoples’ Ministry may find it challenging to compete in the political sphere with stronger and better-funded players as a result, such as technology, mining, energy, and agriculture big corporations.

- Cultural barriers: In the last six years, due to anti-Indigenous governments, the mainstream political discourse has frequently marginalized and antagonized Indigenous Peoples’ views and ways of living, putting them and their leaders in cultural opposition to development and progress. Some sectors and some media in Brazil see Indigenous Peoples as anti-economic development due to Bolsonaro’s and his allies’ discourse.

Indigenous Peoples in politics, land demarcation, and the environment are crucial components of creating Indigenized politics in Brazil. Addressing the historical and ongoing injustices faced by Indigenous Peoples requires a concerted effort from all actors, including governments, civil society, corporations, and individuals.

In one of the sessions of the ATL-Free Land Camp, the Federal Electoral Court (TSE) held a meeting to discuss ways to increase Indigenous participation in the electoral process and facilitate the selection of their own members as political representatives. It seems that sectors of the State are willing to democratically bring Indigenous Peoples to this new scenario, in which Indigenous Peoples are no longer seen as anti-State but with the State and are part of the State. Therefore it is important to note that there are still challenges - historical traumas, alliances with anti-Indigenous sectors - to be faced in achieving true inclusivity and representation of Indigenous Peoples within the State. It will require ongoing efforts to address systemic inequalities and historical injustices, and the new scenario of transition minerals and the so-called green economy.

Minister Sonia Guajara, and the other Indigenous leaders in the Brazilian government, such as Indigenous Health Secretary Ricardo Weibe Tapeba (Tapeba) and Congresswoman Célia Xakriabá (Xakriabá), have stressed that they want to alter politics – Indigenize, decolonize politics – in Brazil. “We want political aldeamento; the goal of our politics is to increase the prominence and participation of Indigenous Peoples in the government, but it also implies a shift in society's attitude toward what it means to be Indigenous in this country," the minister said. “Never again will there be a Brazil without us!” Guajara shouted during the ATL-Free Land Camp.

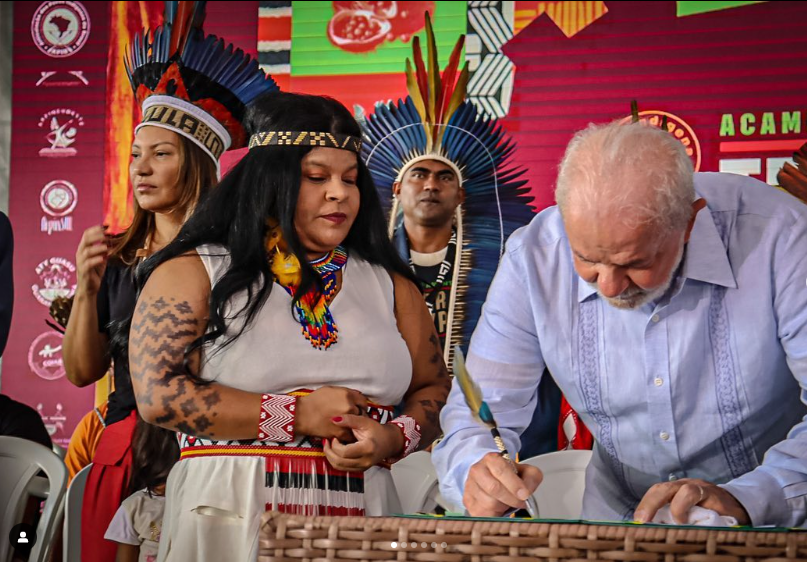

Top photo: Demarcation ceremony - Photo courtesy of @mre_gaviao.