By Edson Krenak Naknanuk (Krenak, CS Staff)

According to the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB), 8 out of 10 Yanomami children in the northern Amazon rainforest are chronically malnourished. The FIOCRUZ Institute, one of the most respected health and research institutions in Latin America, recently warned that 6 out of 10 Munduruku people in the Amazon have high levels of mercury and malnutrition.

In the Alto Catrimani community, on Yanomami Indigenous Territory and the lands of other non-contacted groups in Roraima, a 10-year-old boy weighs just 8 kg when the ideal for his age is around 32 kg (photo below). The image of a boy with his frail body, with bones visible, in the amazon forest is startling. While he comes from one of the richest biomes in the world, he still faces poor access to food. The photo was taken on February 9, 2021, when he was diagnosed with severe malnutrition. Taken to the state capital, Boa Vista, he underwent treatment at the Santo Antônio Children's Hospital, recovered in a state shelter, and has since returned home. However, the factors that cause malnutrition have not changed, but have worsened.

Photo: Marcello Casal jr/Agência Brasil.

Another example of malnutrition amongst Indigenous children is with the Suruí Peoples, aggravated by the historical cases of garimpo (mining) and precarious income distribution in the region. The issue is only alleviated when, due to the assistance of some organizations, access to food is improved.

The sequelae left by malnutrition are not only physical, neurological and psychological, but impacts culture, food habits, physical activities, and overall quality of life. The northern region of Brazil, the Amazon region, is where the highest rate of malnutrition among Indigenous Peoples is concentrated. There is an epidemic of diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension among these communities. A Munduruku source stated, “We can no longer hunt animals, fruits and other forest foods are scarce. When we go out to get food, we don't know if we're going to come back, because the illegal miners in the region are armed and hunt Indians, scare our children and women, kill, and victimize our men and young people.” Even in regions where there are Basic Indigenous Health Units (DESEIs), the structure of health posts is precarious, lacking everything including medical staff, medicines, and food.

The Link between Climate Change, Nutrition, and Indigenous Rights Violations

Climate change plays an increasing and frightening role in the well being and health of Indigenous communities because it not only aggravates the situation, but can irreversibly impact the entire environment where Indigenous Peoples live for generations, including the reciprocal and interdependent relationship they hold with their lands, territories, and natural resources. Floods, droughts, more intense hurricanes, heat waves and wildfires, for example, can drive animals away and destroy plants, ecosystems, crop yields, destroy livestock, and interfere with the transport and trade of food and supplies. It is known that rising carbon dioxide levels from human activity can make staple crops, gardens like rice, wheat, lettuce, vegetables less nutritious and scarce.

Another worrying example, cited many times by Indigenous committees at this year’s United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of Parties (COP 26) in Glasgow, Scotland, is that climate change is bringing massive and unexpected problems such as desertification of traditional areas for bathing and water use in communities in the north and northeast of Brazil. Many communities have faced problems in planning, planting, reduced crop productivity, and food quality.

Related to the previous problems, in recent years the area of large-scale agriculture has substantially increased in the country, especially around the Amazon forest. Agriculture is considered one of the major sources of greenhouse gas emissions in Brazil. Oxen are carbon dioxide emitters because, after eating the grass, they degrade the organic matter inside the stomach and end up generating methane, which is released into the atmosphere by its burping. An example of these emissions, in practice, is the municipality of São Félix do Xingu, Para - near Munduruku and Yanomami lands, which has the largest cattle herd in the country and is the city with the highest rate of CO2 emissions, even ahead of São Paulo, according to data of the Climate Observatory.

Indigenous Peoples in Brazil are not responsible for the climate change challenges as their ways of life never threatened the environment. However, they are on the frontlines of climate change and are experiencing the impacts of climate chaos in very unique ways. Extractive industries cause the contamination of rivers, deforestation, and ecosystem disruption facilitates the transmission of diseases, including COVID-19. They also cause the disappearance of animals, fish, fruits, and other important traditional sources of nutrition for Indigenous Peoples.

The absence and complicity of the State have also contributed to the decline of Indigenous health, well being, and livelihoods. The Brazilian State has been lenient and absent, failing to serve Indigenous health centers, which in many regions are precarious without medication or food. Malaria and other diseases are out of control.

On May 14, 2021, President Bolsonaro affirmed on News TV show: “It is not fair, today, to want to criminalize the garimpeiro (independent prospectors for minerals) in Brazil. It's not because my dad panned for a while. Those problems have nothing to do with these activities.” Days earlier, on May 10, the Palimiu community in the Yanomami Indigenous Land (TI) was attacked by miners.

In addition to the negligence of the State and the anti-Indigenous agenda, there is a growing presence of illegal miners in Yanomami territory – periodically encouraged by the President of the Republic. “Garimpo is the source of all the ills there. In Roraima, at least. If you take out the mining there, look, health, I won't say it would be wonderful, but it would improve a lot,” says Prosecutor Alisson Marugal from the Federal Public Ministry in Roraima (MPF-RR). He is the author of a lawsuit, filed in March of this year, which calls for the restoration of the supply of food in the Basic Indigenous Health Units (UBSIs) to Yanomami Indigenous land.

According to the report, “Scars of the Forest”, produced by Hutukara Associação Yanomami and Associação Wanasseduume Ye'kwana, there are three macroregions most affected by mining in the Amazon, all of them are wetlands by rivers: the Uraricoera, which includes the base centers of Waikás, Palimiu and Uraricoera; and the Parima River, where the Polo-Base de Arathaú is located; and Mucajaí and Couto Magalhães Rivers, where the base centers of Kayanau, Maloca Paapiu, and Homoxi are located. At least nine other base centers in the Roraima, part of the Yanomami Yanomami Indigenous Land, have areas degraded by miners, which also affect nearby regions.

The COVID-19 pandemic represented a deepening of the abyss between the State and Indigenous communities. In addition, the engagement and support by traditional allies of Indigenous Peoples have also been impacted due to the inability of accessing Indigenous lands in a pandemic. Programs, such as Cultural Survival’s Keepers of the Earth Fund, though continue to support Indigenous Peoples on the ground in Brazil because awarding grants does not require travel to those territories to support local, Indigenous communities.

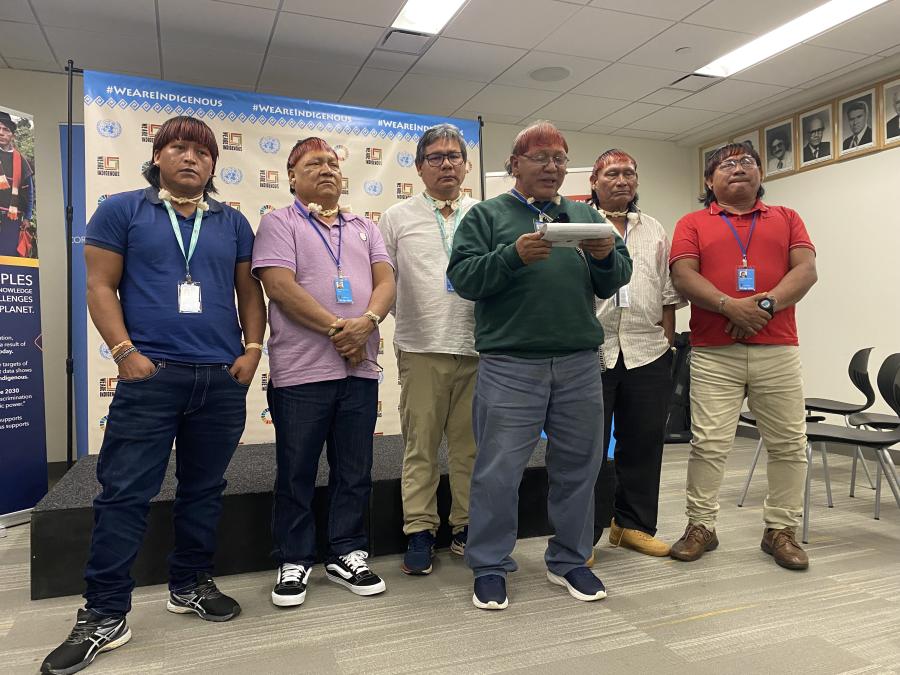

Indigenous Peoples at the COP 26, shared some of the solutions to stop the "colonial systems and structures that impede on our ability to govern ourselves," as Cultural Survival’s Executive Director Galina Angarova (Buryat) points out and to provide proper food supplies for our communities. Some solutions that can address the problem of malnutrition, and combat global warming includes the need to address the following:

- Protect forests and rivers. Completely stopping mining, gold, oil, and metal mines not only stops greenhouse gas emission but also improves the quality of food and life on the planet.

- Regenerate plants, trees, and soil in a holistic, non-extractive way. Indigenous communities are working to not only help the environment but also to protect plants from frost and heat waves.

- Implement more balanced Indigenous production systems that remove CO² from the atmosphere.

- Guarantee the rights of Indigenous Peoples to live safely in their territories. Monica Coc Magnusson (Q'eqchi Maya), Cultural Survival Director of Advocacy, stresses that “Securing land tenure for Indigenous Peoples directly combats climate change and empowering forest Peoples to continue their historical role as stewards of the environment is essential for stabilizing Earth’s climate. When Indigenous Peoples have rights to their lands, they are able to steward these lands in ways that prevent fossil fuel extraction, maintain carbon-capturing forests, ensure soil regeneration and carbon capture through traditional agriculture and agroecology, and protect biodiversity. The gap between recognized and unrecognized land rights points to significant opportunities to scale-up the protection of Indigenous lands…The science is clear—Indigenous communities are critical in reversing the climate crisis.”

- Protect biocultural diversity. Indigenous Peoples’ well being are inextricably linked to the well being of the land. Without biodiversity, human life will cease to exist, and vice versa. For example, the Tremembe Peoples in northern Brazil, after securing their territory, realized that the land was poor and empty. To solve that they are working to renew the local flora with the help of bees - a project supported by KOEF. Bees are essential in the production of food and products linked to basic needs. They account for two-thirds of the food cultures humans eat daily. One in three spoons of food we eat comes from food produced thanks to the contribution of bees, our most important partners. However, large-scale monoculture and the use of insecticides are killing bees worldwide at alarming rates. Supporting place-based, culturally-centered, and traditional agricultural and harvesting practices strengthens, protects, and sustains the interdependent relationships between peoples, place, culture, and ecology.

Photo by JaimeDantas from unsplash

Moreover, in addition to bees, birds are also suffering. A recent study, “Morphological consequences of climate change for resident birds in intact Amazonian rainforest”, detected that 77 species of birds had their body structure altered over 40 years in an area of untouched forest in the Central Amazon. Despite all the accumulated knowledge, all the scientific, economic, and ecological data observed, we are not managing to apply this knowledge to the conservation and protection of the planet.

Indigenous Peoples denounce that during COP26, the commitments made by member states so far are insufficient to maintain global warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2100, and especially ineffective if they continue to exclude Indigenous Peoples from the policies, practices, and finance mechanisms that are aimed to address climate change. We must center and support those on the frontlines of climate change, like Indigenous communities in Brazil who defend their lands from extractive industry and battle issues like malnutrition. Indigenous Peoples' leadership and rights must be centered, operationalized and resources to truly address climate change.

Top photo: Amazonian boy, Mundurku Peoples. Photo courtesy of Antonio Carlos Banavita.