Amidst the strength and power of the Columbia and Spokane Rivers in the ancestral territories of the Spokane Tribe, there is a group of language warriors with the dream of keeping their languages alive. They run the Language House of Spokane using an immersion strategy to increase the number of fluent adult speakers. The Salish language is highly endangered and at risk of disappearing after years of oppression and erasure practices through boarding schools that wanted to eliminate the traditional ways of life of Native Americans. Students were not only taught in the English language but were punished for speaking their Native language.

There is an urgent need to increase the number of fluent speakers of the Np̍oq͗ínišcn language (a dialect of Salish). Only a few years ago, in the Spokane Reservation, located in Wellpinit, Washington, there were only two Elders alive who could speak Np̍oq͗ínišcn fluently. Language House of Spokane started a radical method to address the issue of language loss in the context of a few fluent living Elders. The school's goal is to create the space to immerse adult learners in the Np̍oq͗ínišcn language; later, these students will become mentors and transmit the language to children. Due to the level of endangerment of the Np̍oq͗ínišcn language, the targeted group learning the language includes adults between the ages of 20-30.

Sulustu, Executive Director of the Language House of Spokane, was born and raised in Spokane and is a fluent speaker of Qalispé, Npoqínišcn, English, and Spanish languages. He has been involved in language work for about 20 years and dreamed about a space to actively maintain his language. In 2019, Šitétkʷ joined the dream and contributed to facilitating this language learning space, becoming involved as a teacher. Šitétkʷ grew up on the Spokane Reservation and has been learning Np̍oq͗ínišcn and N˘selˋx̌čin for the last 10 years. He believes that our languages are good medicine for our People and our land.

Other staff members have joined in the last few years. Pše grew up in Montana with her grandparents; both knew the Salish language but never taught it to her. She learned some words in Salish by ear, and she thought these words were in English until later when she learned Salish and she realized she already knew some of the words. Pše caught on to the language very quickly. She did not know why, but it was because she had already heard the sound of Salish. Pše moved to the Spokane Reservation when she was about 15 years old. Part of her motivation to move back to the reservation was to reconnect and learn more about her mother and siblings. More recently, Ctapsqé joined the school as a teacher. He grew up on the reservation. Classes are currently being held at Ctapsqé's grandmother's house until they find a more permanent location.

Sulustu worked for the Kalispel Tribe in 2015 and taught the language every day for three years. In 2018, the Spokane Language House became a reality and classes started with the first N1- introductory level. In the summer of 2018, for 12 weeks and 20 hours a day, 10-15 students came to the Language House and started learning the Np̍oq͗ínišcn language. “The students expressed their feelings about how much their language meant to them and how learning their language changed their lives. It was beautiful to see their growth and healing. This language is very important for our hearts and healing, but it is important for the land because this is the language that the land speaks, that the animals speak, that the river speaks,” Šitétkʷ says.

The Spokane Language House currently has three levels: N1(introduction), N2 (intermediate), and N3 (advanced). The teachers have not yet taught an N3 advanced level class; their goal is to teach the first class in October 2023. The intention is to have a group of adults committed to learning the language full time for two years. The school is currently advocating for funding to pay full time salaries to those learning the language. “You can’t learn the language in one hour a week; you have to have a full immersion... the students will come to the house, cook, clean, and do stuff entirely in the language,” Sulustu says, thus creating a learning experience for students and teachers who will support each other. At the end of those two years of full immersion, there will be new fluent speakers of the Np̍oq͗ínišcn language for the first time more than 50 years.

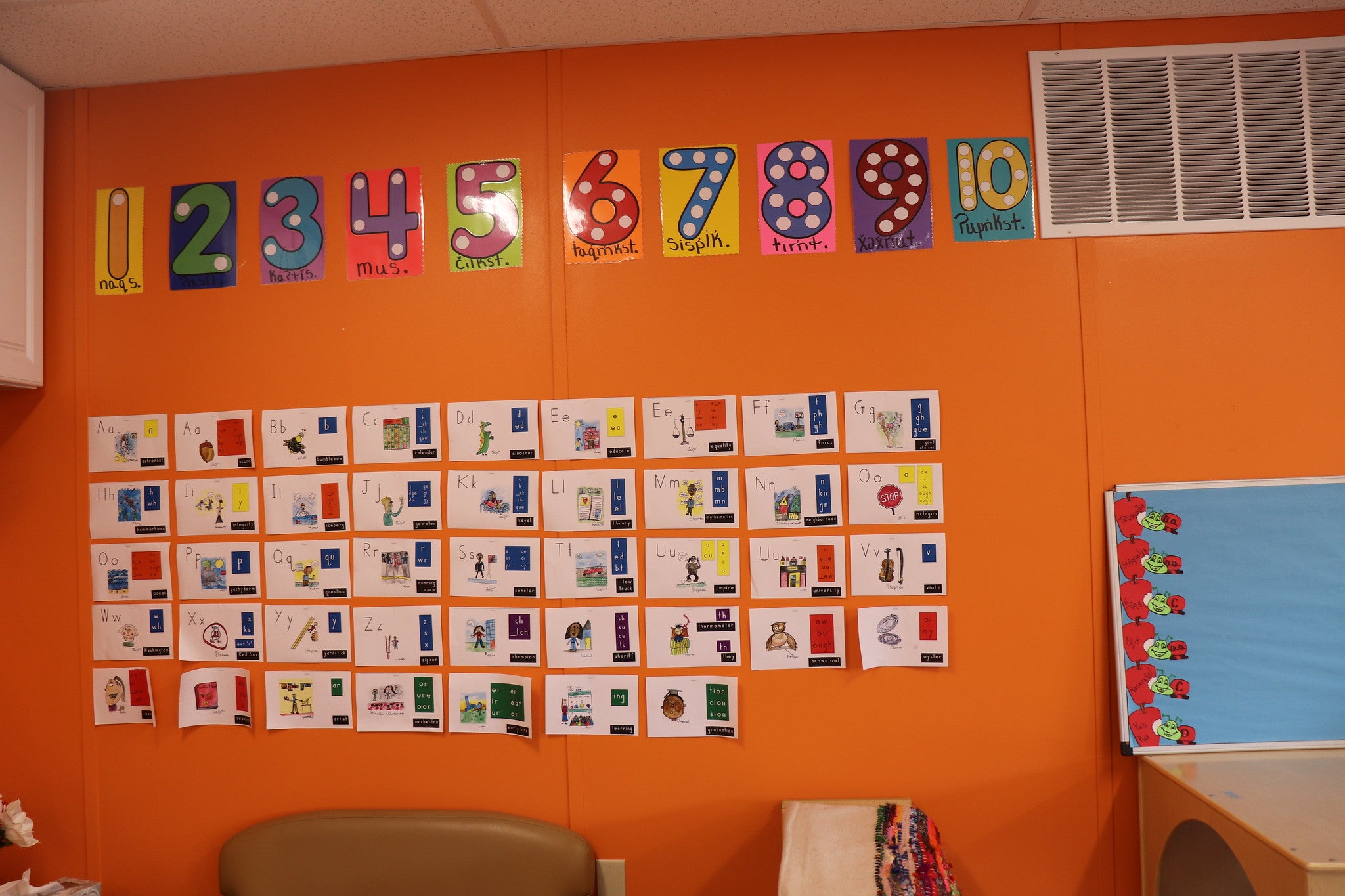

The Salish School of Spokane develops educational material.

Methodology

The Spokane Language House implements a natural approach method, which was developed by the Salish School of Spokane. This method aims to have an immersive classroom in a sequential order where students can build upon their vocabulary and use everything they have learned. “This method is hard because no grammar or alphabet is taught. The idea is to train the ears first and have the students familiarize themselves with the sounds by listening attentively, then repeating, then listening again, and repeating and pointing. Recognition and comprehension are essential in this phase,” Šitétkʷ says.

There are two components of this method: first, the students complete limited production, repeating simple words and sentences. The second component is where the students do full production by using the sentences among themselves and conversing with each other. This method aims to have them speak the language using the words they learned since the beginning of the lessons. Students struggle to learn through this method, but that struggle is what makes them connect all the pieces together.

“We tell our new speakers, ‘you are babies, and that is okay; you are just starting to listen and speak.’ Many emotions come out such as shame, guilt, pride, joy, and some inherited emotions. It is so important to cultivate a safe environment for the students. Overall the whole learning experience is a very transformative process,” says Šitétkʷ. The immersive teaching process can be challenging for the teachers as well as they do not speak words in English, even when the students are struggling. The teachers encourage the students to express their frustrations and feelings in their native language.

Storytelling is an important component of the learning process. Within the limited production phase of the learning method, the students take 40 lessons, and for the full production phase, the students focus on cultural stories and conversing with each other. Storytelling allows the students to figure out all the puzzle pieces; the beauty of the process is that they do it themselves. It is difficult for adults to focus full time on language learning with work and family obligations, so it is crucial to fundraise for salaries for those learning the language full time. These adults are the ones who will carry and transmit the language to our children.

Staff from the Spokane Language House - Sulustu, Pše, and Šitétkʷ.Photo by Cultural Survival

Salish School of Spokane

Located in the city of Spokane, Washington, the Salish School of Spokane is a Native-led nonprofit that provides childcare and early childhood education in the Salish language. The Salish School of Spokane focuses on revitalizing the four Southern Interior Salish languages: n̓səl̓xčin̓ (Colville-Okanagan), n̓sélišcn̓ (Spokane-Kalispel), n̓xaʔm̓xčin̓ (Wenatchee-Columbian), and sn̓čic̓úʔum̓šc̓n̓ (Coeur d'Alene).

Started by LaRae Wiley, a member of the Sinixt Arrow Lakes Band, and Christopher Parkin, her husband, the school opened its doors in September 2010. Year by year the school has grown and has had up to 58 students, except during Covid, when enrollment dropped to the lowest number since 2014. Since the pandemic, they have maintained an average enrollment of 33 students.

The Salish School of Spokane aims to educate children up to high school through the Salish language and ensure that children connect with their families, who they are, and where they come from through the language. While the school focuses on working with children, the staff also offers a community space for adults who want to learn the language, mainly parents of the children attending the school. The school additionally offers language classes to all staff members who work at the school.

A Comprehensive and Natural Approach to Learning Salish

“All children should learn to read and write in their native language. They have the right to do so,” says Parkin. At the Salish School of Spokane, all subjects (science, math, and music) are taught in the Salish language. The Salish School of Spokane envisions a learning environment where students are immersed in every aspect of the Salish language. Through a natural approach method, the students learn Salish with limited use of English.

Staff members at the school have spent hundreds of hours reviewing archives, translating materials, and developing a curriculum that has been shared with other grassroots language revitalization projects in Washington State and Montana. Parkin and Wiley believe in the power of exchanging ideas with other language revitalization initiatives and sharing materials, curriculum, ideas, and methods. They agree there is a need to facilitate a space where the initiatives increasing the number of fluent speakers share their resources with other Indigenous relatives because, in the end, it is all about acting now as the Indigenous language loss rates grow.

L-R: Christopher Parkin, LaRae Wiley, Adriana Hernández (CS Staff) and Nati Garcia (CS Staff) at the Salish School of Spokane. Photo by Cultural Survival.

Top photo: Columbia River. Photo by Cultural Survival