By Phoebe Farris (Powhatan-Pamunkey)

Wingapo means “welcome cherished friend” in the Algonquin language and is a good way to describe the events that took place at the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C., on July 8-10, 2021. Wingapo! Welcome to the Native American Dance Circle featured live performances and multigenerational interactive programs showcasing Indigenous cultures through music, film, dance, storytelling, and an artists market. Curated by Rose Powhatan (Pamunkey and Tauxenent), Co-founder and Director of the Powhatan Museum of Indigenous Arts and Culture, the vibes between the performers, audience participants, and artists were indeed welcoming. Despite rain cancellations, the first two days, the July 10th day, and evening activities at the outdoor REACH arena were so dynamic and energizing because of all the live performances that people forgot about their rainy day disappointments.

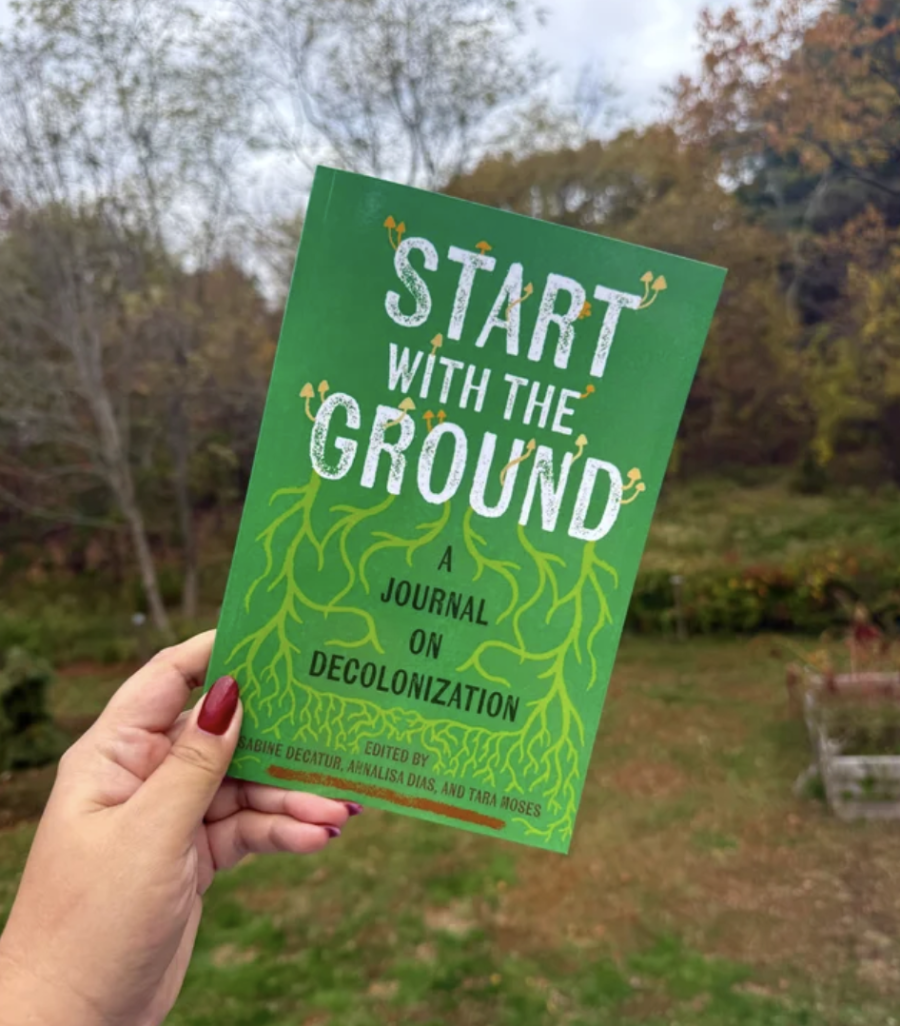

Totem to Powhatan created by WINGAPO! curator Rose Powhatan (Pamunkey and Tauxenent) and her husband Michael Auld (Taino).

Daytime highlights began with a morning yoga class called Warrior Yoga with Edward Keith Colston (Tuscarora and Lumbee), followed by a friendship dance class with Angela Miracle Gladue (Cree from Canada), hoop dancing with Meredith Lam (Navajo), storytelling by Rose Powhatan, a flute performance by Nathan Elliott, (Nottoway), a hip hop dancing class with Angela Miracle Gladue, and DJ sets with Urie Ridgeway (Lenni Lenape). The evening ended with a jam-packed crowd that came to see and to hear Red Crook-ed Sky Dance Troupe and the Stoney Creek Singers which was live-stream on YouTube. The Stoney Creek Singers are Northern-style powwow singers from North Carolina and the Red Crook-ed Sky Dance Troupe is based in Virginia.

Hoop dancer Meredith Lam (Navajo).

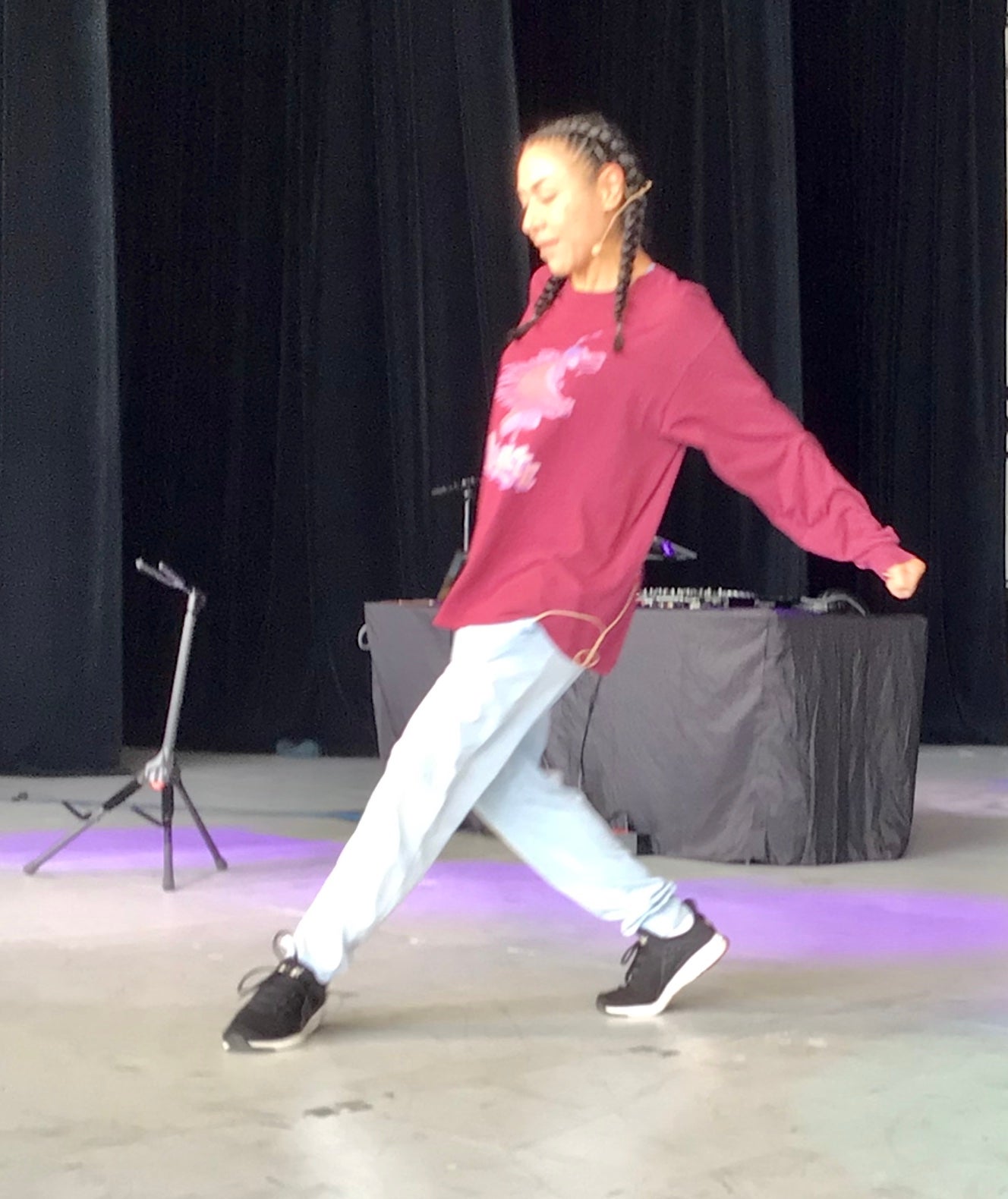

Angela Miracle Cloud (Cree from Canada) teaching hip hop moves.

During brief intermissions, performers and artists market vendors shared their stories. Artist James E. Whitley III stated that he primarily paints in acrylic on canvas or on wood. When asked what inspired him to paint a portrait of his great aunt Georgia Mills Jessup (Pamunkey) whose painting, Rainy Night Downtown, hangs in the permanent Contemporary Collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA), Whitley replied, “In conjunction with the event Rose Powhatan commissioned me to paint her mother. My grandmother Fannie would always tell me about her sister who was an artist. Rose gave me an NMWA postcard that had Georgia’s painting on it. It was the same piece of art that I used as inspiration for the background of the portrait. In the painting, Georgia is wearing two pieces of Indigenous jewelry that she wore in real life. Also, I think of my painting style almost like war paint using patterns and marks to render my images.”

James Whitley III at his booth featuring his prints and his recent painting of artist Georgia Mills Jessup (Pamunkey), his great aunt, whose work is in the permanent collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts located in Washington, D.C.

Whitley said that he is a big fan of pop culture and in the past, his subject matter was often inspired by comics, film, or gaming. “Most recently my commission work has been of people who have passed on. It is a huge honor and burden to be able to paint a loved one. I have a very textured style. I like for people to be able to see my brush strokes because I want the viewer to know that there is a creator behind the piece,” he added. When asked about his overall impression of the Kennedy Center’s Wingapo! events, Whitley replied, “The event was such a great celebration of Native American culture. It was great seeing the culture respectfully celebrated by all those who attended. I would love to participate more in other events.”

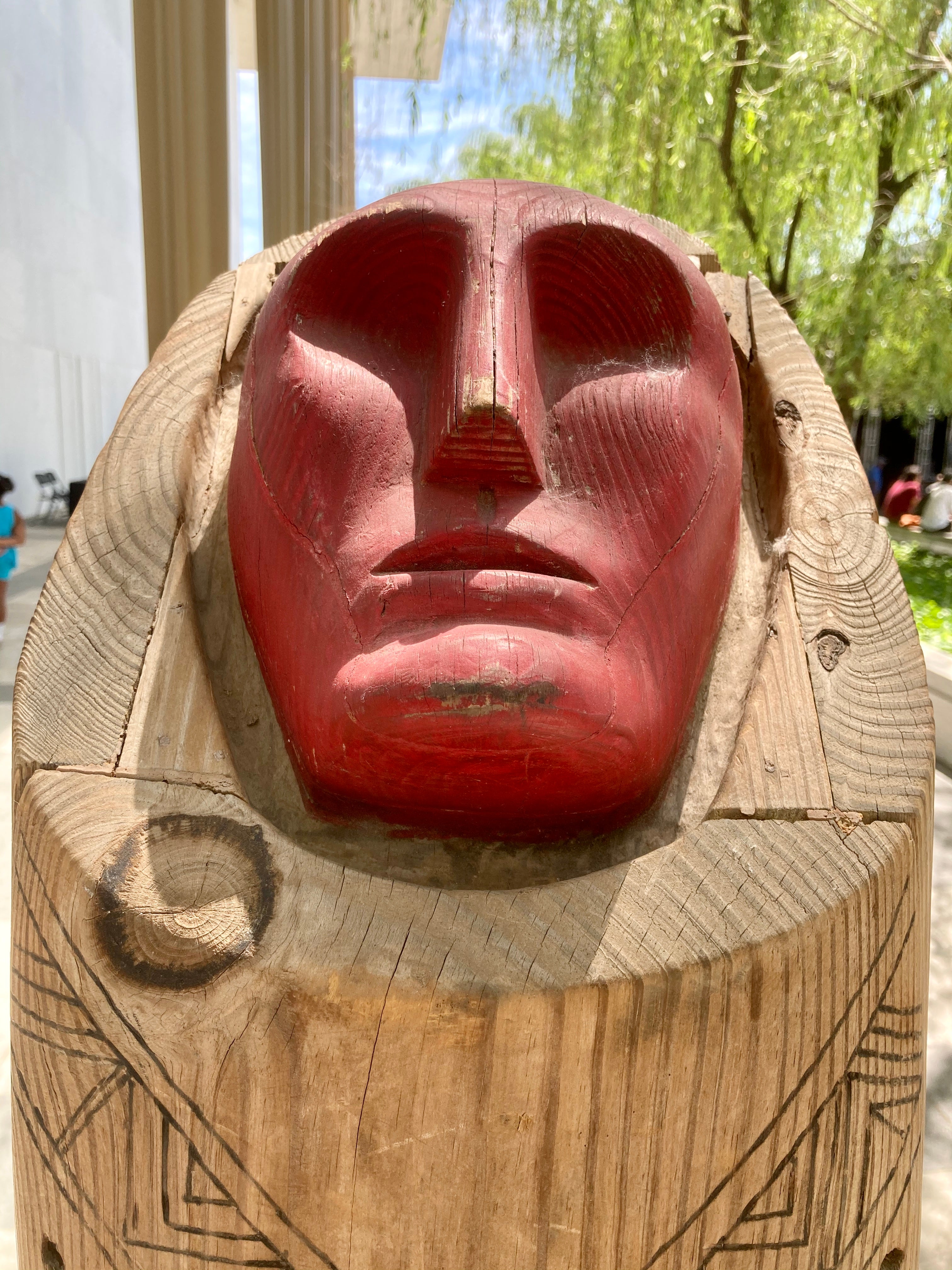

Cedar sculpture of a warrior by Nathan Elliott (Nottoway).

Nathan Elliott spoke about his involvement with flute music and stated that he always liked the sound of the wood flute because “its soft intimate sound that is made through a hollow wood cylinder brings you closer to nature and I believe we all have some inner connections to the different sounds nature makes.” Inspired by his mother, Jackie, to get involved in music and learn to play instruments, Elliott first studied the saxophone but ended up preferring the flute. Now, he makes different types of Native American flutes, his favorite being the river cane or bamboo flute. “It is considered a southern woodland flute because of the location where you would get river cane from to make the cane flute.” One of Elliott’s flutes is on permanent display at the Jamestown Settlement Museum in Virginia. Some of the songs he performed at the Kennedy Center were his own compositions, one was traditional, and another one was more modern in style.

Nathan Elliott (Nottoway).

Elliott is a third-generation woodturner and grew up watching his grandfather, Archie, and father, Billy, make wooden bowls, other home utensils, and bracelets. Much of his inspiration comes from past traditional Eastern Woodland artifacts but he adds his own modern touch. He believes that Native American art should evolve but also incorporate traditional elements. “Much of the wood that was used to make my wooden bowl came from my father’s land in the Deep Creek area of Chesapeake, Virginia. Some of my arts and crafts are being sold at Virginia Fine Arts Museum, Colonial Williamsburg, National Park Jamestown Island, and the Portsmouth Arts and Cultural Center.” When asked about his overall impressions of the Wingapo! events, Elliott replied, “It was an honor for me and my daughter, Eliana, to be here and to be a part of this historical event at the Kennedy Center. I feel like it has been a great educational and cultural event and it should happen every year so that the world can see who we are, where we have been, and where we are going. I would love to come next year and share my Nottoway culture. We should never be put in a box of the past. We are still here, never have left, and are always evolving.”

St. Regis Mohawk Basketry.

Chastity Hart and her family were vendors and described their Mohawk arts, “Traditional basket making is a dying art. At one point in time, there were only five traditional basketmakers from our territory. Individually, we all have an interest in preserving this tradition and were taught in some way, however, we do not consider ourselves as basketmakers. A basketmaker is a title that takes years to earn and within our family, only our sister-in-law has that title. Traditional baskets from the St. Regis Mohawk Territory (a.k.a. Awkesasne) [located on the international border between Canada and the United States] are only made with sweetgrass and black ash splints. This is how you can recognize that it is a Mohawk basket. Traditionally, baskets were utilitarian, with no decorative designs. The baskets have become decorative works of art, especially with the inclusion of sweetgrass. Sweetgrass was incorporated in the basket design for its’ fragrance. The most frequently requested design is the Haudenosaunee symbol.” Hart says that the Wingapo! event “opened our eyes to a need for education and awareness about our Peoples, Tribes, and traditions. We answered numerous questions about our Tribe and our traditions. We were amazed at how many people were unfamiliar with our traditions.” Hart also shared her Tribal pride about lacrosse, “We are also famous for our lacrosse sticks. One of our family members owns Mohawk Lacrosse (aka Mohawk International Lacrosse), one of the few remaining manufacturers of lacrosse sticks on our reservation. The game of lacrosse is a gift to amuse the Creator and heal the sick. It is still a ceremonial game for our people. Today around here the men still use the wooden stick. The people of this reservation and other reservations still practice keeping the tradition alive.”

Edward Keith Colsten (Tuscarora and Lumbee), yoga instructor and traditional Native dancer who incorporates Native American dance poses and movements with yoga poses and movements.

In addition to all the performances on stage and audience movement participation on the ground, attendees were given the special opportunity to work with Steve Prince, the Distinguished Artist in Residence and Director of Engagement at the Muscarelle Museum of Art at William and Mary University. Steve Prince and participants made a 10x10 foot reproduction of Jaune Quick to See Smith’s “Tourist Season” in chalk, to help advertise the National Chalk Art Mural competition sponsored by William and Mary University. Prince shared, “I designed the National Chalk Art Competition as a response to the pandemic and the fact that we were sanctioned by the government to stay in our homes and limit contact with people for over a year. The competition, and conversely art creation that the project encourages, becomes a conceptual balm for us to continue to find our path back to ‘normalcy’ by utilizing the transformative nature of art making as a tool to help us find paths to communal health. I endeavored to showcase the competition at the Kennedy Center to encourage the public to join in on the fun. I was fortunate to have the opportunity to create a chalk art image at the Intertribal Native American Dance Circle WINGAPO and it was only appropriate that I did a work that championed the Native American spirit and culture. The Muscarelle Museum has over 100 Native American works in its collection, so I chose one of the images that we were promoting in the competition and engaged the community in replicating the artwork by Jaune Quick to See Smith, titled Tourist Season. Smith's work is layered with colors, symbolism, and filled with calligraphic gestural marks reminiscent of the musings of a child, but couched in a deep, sophisticated compositional structure that I thought would be both challenging and relatively easy for a group of people to recreate.” Prince commented that he was most pleased with the atmosphere and sense of community that was present at the site because of the WINGAPO. Prince shares, “I was honored to be a part of the Wingapo! experience and to witness the beauty, pageantry, and richness of Native cultures that have been passed on this generation and beyond. I look forward to continuing to find ways to expose the truth, and fight for true reconciliation for both Native Americans and African Americans."

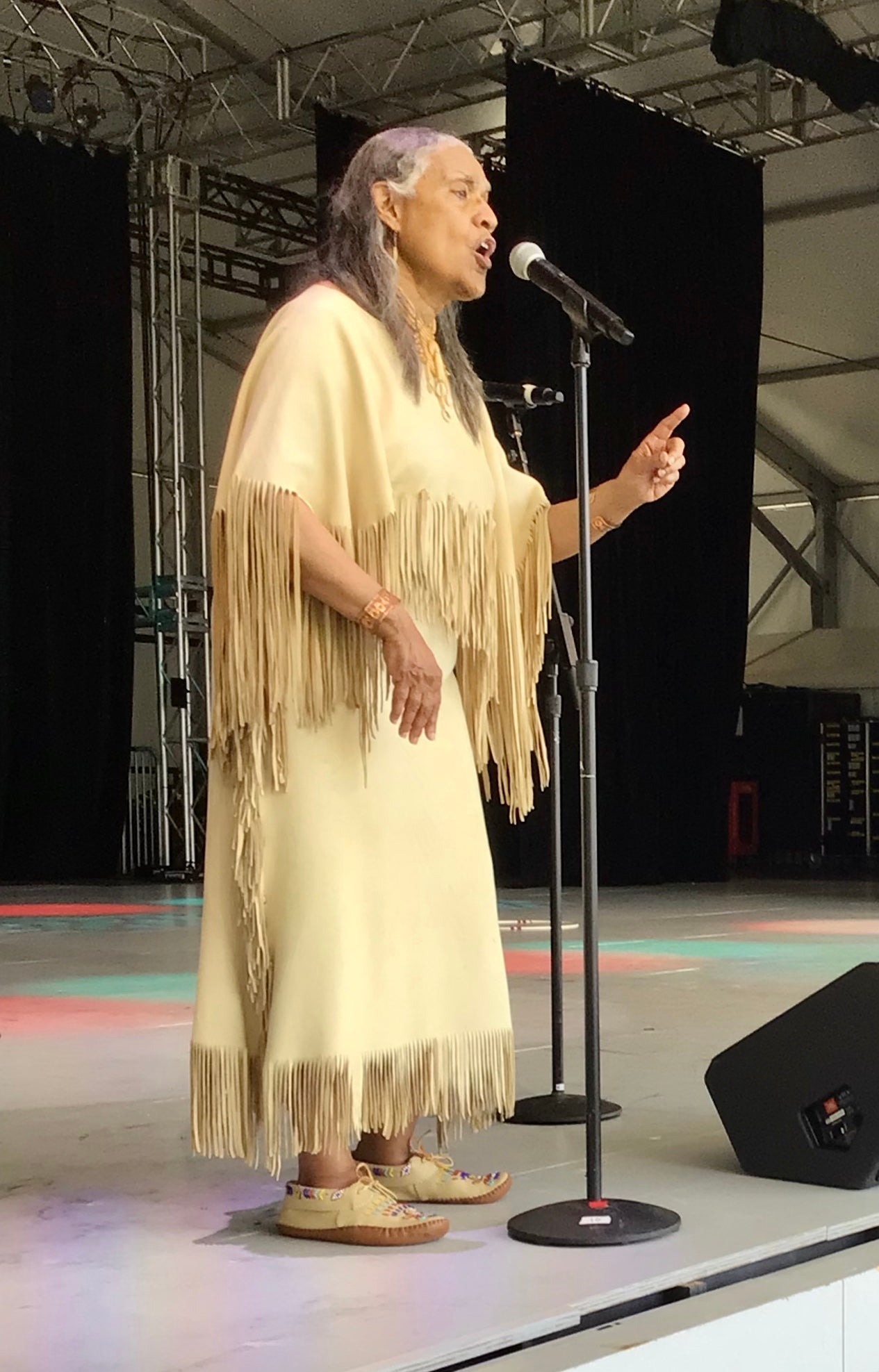

Rose Powhatan(Pamunkey/Tauxenent) singing and storytelling.

Rose Powhatan has served on the Kennedy Center’s Advisory Board for over 20 years and a member of its inaugural Culture Caucus for over a year. As the only Native American on both committees, she gives voice to the Native American cultural community of the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia as well as on a national level. Powhatan discussed the Kennedy Center’s “imperative to commission and stage new experiences for its audiences from Indigenous artists across the performing arts spectrum, ranging from the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa), Yalitza Aparicio Charon (Mixtec/ Triqui), the Oscar-nominated actress for the film Roma, and to regionally known Indigenous performers.” Powhatan first conducted a land acknowledgment for the launch of the REACH Opening Festival on September 7, 2019, which was followed by a day-long Indigenous Day on September 10 at the Kennedy Center the same year. People are looking forward to more Indigenous programs and then the COVID-19 pandemic happened. Scheduled performances for the Kennedy Center’s Millennium Stage moved outdoors to be in compliance with CDC protocols. It became the Millennium Stage Summer at the REACH where free weekly outdoor performance experiences took place. Powhatan was asked to curate a three-day Indigenous weekend of performances, film, DJ music, and a mini arts and crafts market. “WINGAPO! Welcome to the Native American Dance Circle was planned to be an Indigenous, interTribal performing arts homecoming at the Kennedy Center. Performers either lived in the DMV area, or were members of nations that had historic ties to D.C., Maryland, and Virginia. In traditional Southeastern Indigenous communities, the Dance Circle has always been the heart of the village. It is a place of ceremony and celebration. Our WINGAPO! event brought the dance circle back home to the Kennedy Center. In true Indigenous tradition, I blessed the grounds and did a Land Acknowledgement before the performances started,” Powhatan shared.

Karen McCoy left and her sister Yvonne Turtle McCoy, spectators at Wingapo!.

Powhatan also acknowledged her appreciation for all the vendors who set up tables with a variety of traditional and contemporary arts and crafts. Vendors included Ani Begay Auld (Navajo), Charlene Thomas and her family (Mohawk), Sharon Folgar (Navajo), Nathan Elliott (Nottoway), James Whitley III (Pamunkey), Selina Kyrete (Dine), and Powhatan Intertribal Museum-Michael Auld (Taino). She said that she and everyone in attendance were especially delighted by Saturday evenings Grand Finale performances featuring the Red Crook-ed Sky American Indian Dance Troupe, directed by founder and head dancer Keith F. Richardson (Assistant Chief of the Nansemond Indian Nation) and the Stoney Creek Singers, under the direction of Dr. Marvin Richardson (Haliwa-Saponi). As many others and Powhatan expressed, “A good time was had by all. It was both entertaining and educational. Many in attendance asked me the same question, when will the WINGAPO! Intertribal Dance Circle come back again?”

-- Phoebe Farris, Ph.D. (Powhatan-Pamunkey) is a Purdue University Professor Emerita, photographer, and freelance art critic based in NJ, NY, and Washington D.C.

All photos by Phoebe Farris.