Unnoticed by most passers-by, there’s an old yellow house in Sapulpa, Oklahoma that is the meeting place of the world’s only living experts on a unique language and culture, called Yuchi. Something remarkable is going on inside the “Yuchi House”— native speakers of this ancient language are conversing and passing on their vast knowledge to younger learners. Only five elders who were raised as monolingual Yuchi speakers are living today. All of them are in their 80s and 90s. Henry Washburn, Josephine Keith, Maxine Barnett, Josephine Bigler, and Martha Squire have chosen to dedicate their last years to keeping the language alive by teaching Yuchi youth. They are motivated by a deep sense that they are the last keepers of an ancient way of being in the world, which will be lost forever if they do not act quickly.

After millennia of Yuchi language speakers, the current elders are the last link to this storehouse of human knowledge and the eons of tradition, cultural practices, spiritual understandings, and unwritten history. Learners and elders alike realize that the only way to keep the language going is to transmit it face-to-face and breath-to-breath, as it was from mother to child.

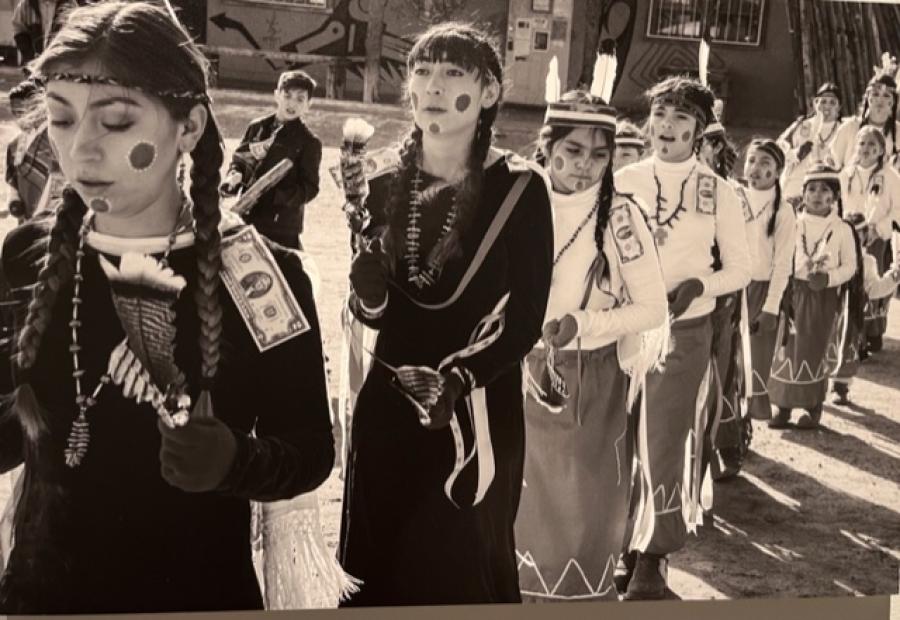

The Yuchi House is home to a variety of language revitalization efforts put forth by the Yuchi community. Each morning, the house is filled with the fluent speech of elders and younger language bearers who are eager to learn. In the afternoons, the Yuchi House emits the laughter and footsteps of over 30 children and youth who attend a daily afte rschool program conducted in the language. Elder speakers are involved in the children’s program, however the younger language bearers do the primary teaching and management of the kids. This ‘triage’ system of language learning allows all generations to learn without exhausting the elders.

The success of the program is due to the fact that Yuchi children are once again speaking the language, naturally and intuitively. For the first time in over 60 years, young children are once again getting in trouble in school for speaking Yuchi. When Taygann Spencer entered an English kindergarten she had already been learning Yuchi for a few years. When her new teacher tried to teach the color “red,” Taygann would only say “chathla” (red in Yuchi) because she did not know it in English. The teacher thought she was speaking Spanish and sent her to a special speech class for English-as-a-second language students. When her father, Yoney Spencer, explained that she is speaking Yuchi and he encourages it, the teacher replied that she doesn’t want her to speak Yuchi in class because she doesn’t know what she is saying. When Taygann asked her dad was what going on, he said, “They want you to speak English.” She asked, “What’s English, daddy?” To her, there was no linguistic dichotomy between Yuchi and English, she was just communicating in the only way she knew how.

“A Yuchi parent got up in church during the time for sharing and joyfully with tears in her eyes said that her daughter, Lillie Mae Wilson (age 3), started speaking to her in Yuchi during a visit to the state fair, about what she was seeing at the petting zoo area. This is an example of the kind of breakthroughs we are having after 70 years of no children speaking Yuchi.”

Each of the five elder speakers is gifted in different aspects of the Yuchi language. Some are more fluid storytellers, some are more precise in pronunciation or remember particular uses of a term. Notably, only one is male. K’asA Henry Washburn, 87, is the only male speaker among the elders living today. Because men and women speak differently in terms of pronouns, noun classes, and family terms, K’asA is the only person who can teach young men how to speak the male version of the Yuchi language. Yuchi men carry the important responsibility of giving tobacco to the deceased in order to reunite them with those who have gone before them. This ceremony can only be conducted in the language and fortunately over the past few years K’asA has been able to teach other Yuchi men how to properly carry out this ceremony.

Martha Squire has taught us important aspects of the language. She happened to be in the Yuchi House the day we were talking about familial relations. She pointed outthat when women speak about their Yuchi mothers or grandmothers, it’s proper to use an “honorific” pronoun instead of the typical Yuchi female pronouns. For example, instead of saying “my grandmother” “dElaha sAnû,” the proper way is “dElaha Ânû.” Martha is the last living person who could have taught us this socially and culturally important part of the language. We are continually uncovering new gems like this in our voyage to learn Yuchi and are constantly struck by how dull and vague English seems in comparison.

As a former college student, I have been trained to use books, journals, or online resources to answer questions in the English language. As a student of the Yuchi language, there is no google search that can answer any question I have about Yuchi. Yuchi is a purely oral language with very little documentation. The elders are our only resource and are our “living encyclopedias.” The whole Yuchi world is contained within the minds and hearts of these five elders.

If you find yourself driving by the Yuchi House someday, remember that it is a miraculous place where the seemingly impossible becomes possible—our once moribund language is breathing new life. Each day, we are in a race against time to glean new treasure from the minds of our elders while we still can. Truly, our elders are more precious than gold and the gifts they bear to us far exceed any tangible treasure.

The Yuchi Language

The Yuchi language is an isolate, it is not related to any other language. Yuchi reflects concepts and perspectives that do not exist elsewhere. The sense of Yuchi community is so fundamental to Yuchi thought that the language always marks whether or not you are speaking about a Yuchi person by using different pronouns for Yuchis and non-Yuchis. If I say “I see a woman” I must say whether or not she is Yuchi, w@nt’A sAdE’nê (Yuchi) or w@nt’A wAdE’nê (non-Yuchi). There is no way to talk about someone in a generic sense. The “wA” pronoun refers to any non-Yuchi person, including men, women, animals, the Sun, moon, etc. It is very hard to think of humans as categorically different or superior to those called “animals” in European languages.

We call ourselves szOyaha, “People of the Sun.” Our language has deep connections to the environment. Our physical relation to the earth is also reflected in the language. A speaker of Yuchi is always paying attention to the physical relationship between persons and objects and the earth. You can’t just say “there it is;” you must say whether “it” is standing, sitting, or lying in relation to the earth. If it’s an apple, “aKA-chE” (there it is-sitting); if it’s a river, “aKA- A” (there it is-lying). The pronouns also carry over to people: “KA dO chE” (I am here-sitting), “KA dE fa” (I am here-standing), and “KA dE A” (I am here-lying). In English we simply say “I am happy” but in Yuchi we say, “zAdOsh@nlA KAdOchE,” which in direct translation means “I am happy—I am here-sitting.

—Renee Grounds is a Yuchi language instructor.

To learn more about Yuchi visit :/elp/yuchi