"Perhaps many of its will have to write our Indian history with blood, but one day we will make the V of victory to the government an to FUNAI. We will be victorious." - Marcal Tupa-Y (Guarani leaders assassinated on 25/11/83)

During the past year the Brazilian Indian movement made enormous strides in promoting progressive changes in national Indian policy. Simultaneously, Indian communities confronted a wave of violence and a series of hardline government decrees that threaten to undermine completely their constitutional and legal rights.

In early 1983, the National Indian Foundation's (FUNAI) responsibility to guarantee Indian land rights became meaningless when a presidential decree transferred the job of demarcating Indian lands from FUNAI to an interministerial work group comprised of federal and state agencies. Having failed to fulfill its promise to demarcate all Indian lands within five years after the passage of the Indian Statute in 1973, FUNAI was relieved of the responsibility altogether. The agencies now responsible for land demarcations - including the National Security Council, the Ministry of the Interior, and state agencies - are notorious for their political and economic interests and their persistent efforts to undermine Indian rights.

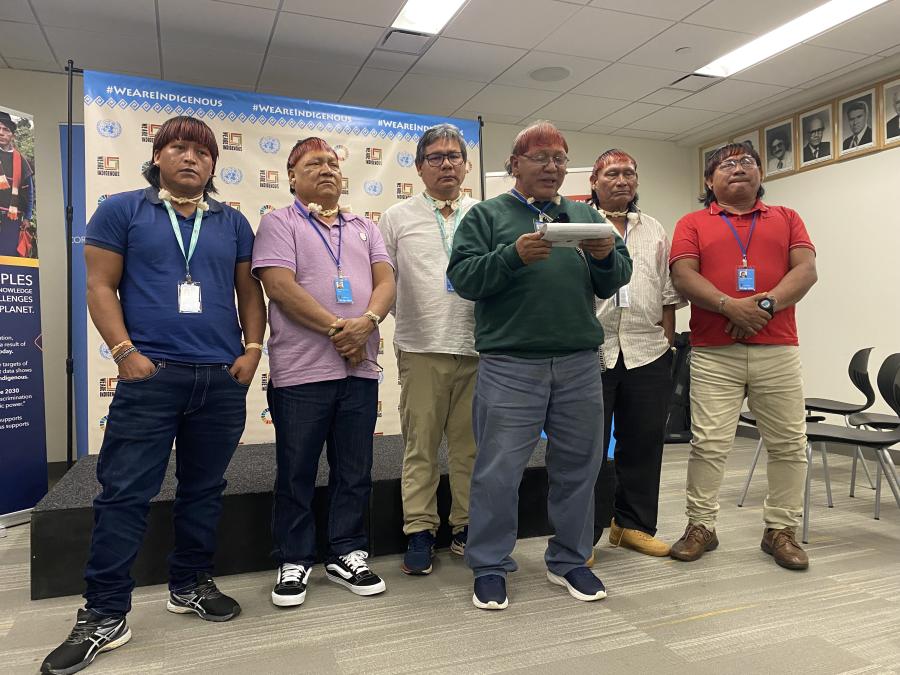

In view of this situation, in March, 1983, Mario Juruna, Xavante leader elected deputy to the National Congress (PT/RJ), presented a proposal to the Brazilian Congress for the creation of a special Indian Commission that would formulate opinions about assistance to Indian communities, agencies related to indigenous interests, and relations between Indians and the national society. Specifically, the Commission would receive and investigate denunciations and other documents about Indian affairs; propose legal measures for the defense of Indians and the ecology of indigenous reserves; and investigate the enforcement of legislation defending Indian rights. Congress passed the proposal unanimously in early May.

Encouraged by the Congress' favorable reception, in April Juruna presented a second proposal calling for a restructuring of FUNAI's directorship. The directorship would be formed of Indians appointed by indigenous communities or recognized indigenists knowledgeable about the Indian situation in Brazil. A national council of five leaders would oversee the new directorship while regional Indian councils would be formed from local Indian leadership. Juruna foresaw the creation of an indigenous federation, integrated at the local, regional, and national levels, to formulate Indian policy and to have direct connections to legislation through the Indian Commission in Congress. Juruna's proposal is still pending Congressional approval.

Radical changes in FUNAI were forthcoming even before Juruna's proposal was debated, however. Xavante leaders of Mato Grosso - increasingly irritated by invasions of their lands and by news of the assassinations of Indian leaders - decided in June to visit the national offices of FUNAI in Brasilia. On several occasions in the past three years, the Xavante have demanded the dismissal of the military officers in charge of the agency, charging that they were corrupt and insensitive to Indian problems. One example of corruption they cited was FUNAI's tactic of creating divisions in Indian leadership by promoting leaders most supportive of FUNAI policy.

On 23 June 1983, a delegation of fourteen Xavante accompanied by several other Indians - later joined by Juruna and five other federal deputies - occupied the national offices of FUNAI, expelling the two colonels who happened to be there at the time, and demanding a purge of the 22 colonels in the directorship of the agency. Their demands were heard: ten days later, President of FUNAI Paulo Moreira Leal and at least half a dozen other top-level military officers were dismissed from the agency. Leal was replaced by a civilian from the Ministry of the Interior, Otavio Ferreira Lima, who had previously served two years in FUNAI under President Joao Carlos Nobre da Veiga.

Even under civilian direction, the inherent problems of FUNAI could not be resolved. Lacking any power or funds for assistance projects, the agency floundered as pressures on Indians and their lands increased. The fate of the Pataxo Indians of the Caramuru-Paraguacu reserve in the state of Bahia hung in desperate balance as a state court deliberated on whether to reinstate the Indians on their contested reserve. In 1949, the Pataxo were pushed off their reserve because the Service for the Protection of the Indian (SPI, FUNAI's predecessor) had illegally leased the Indians' lands to various land-grabbers (grileiros). In early 1982, the Pataxo were encouraged by FUNAI to reoccupy the Sao Lucas Ranch in the heart of their reserve. After severe threats and pressures from cacao-growers of the state, FUNAI later removed the Pataxo to a government-owned farm. When elections brought in a new state government, the Indians returned to the Sao Lucas Ranch and the whole matter was then brought into state court. For months, the court deliberated while the Indians, without a water supply, were surrounded by Federal Police and physically threatened by ranchers. In an act of despair, one leader, who had opposed FUNAI's efforts to persuade the Pataxo to cede their lands and accept relocation, murdered a leader whom FUNAI had succeeded in persuading. By September, it seemed that the Pataxo would lose their lands in court. At that time, FUNAI cut off all food supplies to the Indians.

Anthropologists, pro-Indian groups, and Indian leaders spoke out on behalf of the Pataxo. In a speech before Congress, Mario Juruna remarked that all of the ministers of Brazil were "thieves" - guilty of robbing lands and allowing people to die. Although his remark was made more in the manner of a chief exhorting his people to respect the laws than as a denunciation of individual ministers, the Brazilian Cabinet of Ministers took it as a personal insult. They called on the Congress to expel Juruna or otherwise censure him. If that was the outcome, Juruna replied, he was prepared to travel to Europe to bring the situation of Brazilian Indians to international attention. For days, front-page news stories followed Juruna's case, while telegrams of support came from around the world. In the end, despite pressure from the Ministry, Congress decided only to censure the deputy's remarks.

The publicity surrounding Juruna's case may have helped to turn the tables for the Pataxo, for in early November, the state court of Bahia ruled favorably on the Indians' rights to remain at the Sao Lucas Ranch. The case is by no means closed, however. The Brazilian Supreme Court must now decide whether the Indians will regain the entire 36,000 hectares of land they claim. Meanwhile, threats of physical violence against the Indians continue to come from the Federation of Agriculturalists in Salvador, Bahia. An immediate consequence of the Pataxo case was that FUNAI lost the right to control police or military intervention in Indian areas. An interministerial document passed in September gives any interested parties the right to call federal or military police into areas of tension or conflict involving Indians.

A severe blow to Indian land and resource rights came in November when the Brazilian President signed decree no. 88.985 opening up all Indian areas to mining by federal, state, or private companies. The justification for this decree rests on reconciling Brazil's perceived need to develop its mineral resources, while simultaneously preventing the growing problem of uncontrolled entry into Indian lands by individual mineral prospectors. While the government argues that mechanized mining will be less harmful to indigenous communities and the environment, the decree has already opened Indian lands to large-scale corporate invasion. According to reports from Brazil, over 300 requests for mineral exploitation were made in the first month since the decree was signed. Reportedly, Brazil intends to pay part of the interest on its national debt by exporting some US$500 million worth of minerals from Indian lands in 1984.

Numerous objections have already been raised concerning the decree. For instance, it is doubtful whether mining's adverse effects will be better kept in check by corporations than by individual miners. Even in cases where companies, under pressure from international agencies, have recognized indigenous rights, communities have been forced to sacrifice their lands and resources to development, e.g. the Gavioes, Xikrin, and other Indian societies in the area of the Carajas Iron Ore Project in northeast Brazil. While the decree calls for the participation of Indians as laborers in mining projects, it does not give communities royalties for extracted minerals, compensation for the general disruption to their lives and environment, or the right to decide whether mineral corporations should be permitted on their lands in the first place. The decree contradicts the Brazilian Constitution, which guarantees the Indians' permanent possession of the lands they occupy. The decree also does not distinguish between indigenous peoples in different stages of contact with the national society; in cases of minimal or no contact - as with the Yanomami Indians - corporate mining poses a serious threat to the survival of the Indians. Since 1975, pressure to open up Yanomami lands to mining have intensified and left their mark: many Indians have died as a result of epidemic diseases, many others today suffer from tuberculosis and venereal disease introduced by miners. Finally, the decree places an enormous burden on FUNAI which would be required to consider, case by case, the consequences of allowing mining companies to enter Indian lands. FUNAI does not have the capacity for this type of constant review.

At the same time the government struck at indigenous resource rights, it presented a new civil code for congressional approval which, if approved, would downgrade the status of Indians. At present, Indians are defined as "relatively incapable" in law and therefore require an Indian agency to assist them. Under the new code they would be redefined as "absolutely incapable." They would no longer have the right to be assisted to express their wishes by the Indian agency as before, but would be deemed incapable of formulating their own views on their own interests. The state would be legally entitled to speak for the Indians on all matters.

Such a downgrading of Indian status stands in total contradiction to the Brazilian government's repeated efforts since the late 1970s to fully "emancipate" the Indians from their status as wards of the state. The latest attempt to do this is a legal project pending in Congress which proposes the compulsory emancipation of all Brazilian Indians. This project contradicts the proposed alteration of the civil code for it would be absurd to "emancipate" people who are considered "absolutely incapable."

But there are more serious objections, set out by Indians and their supporters, to "emancipation" proposals. "Emancipation" would abolish the present laws to protect the Indians and the agency charged with enforcing them, thus removing any legal basis for protecting Indian rights. "Emancipation" would not, as the name implies, free the Indians from any legal disabilities; rather, it would free the state from its responsibility of protection. Further, emancipation under Brazilian law would make communal land holdings, the basis of many Indian societies, illegal and would strike at the cultural and physical survival of Indian societies. In the words of one Indian leader, "It would take away from us all possibility and every weapon we have to protest the infringement of our rights."

Both the proposed alteration of the civil code and the emancipation projects would be disastrous for Brazilian Indians. FUNAI's current role as the Indians' legal guardian still presents many difficult problems but as history has shown, these have largely been due to the agency's relative incapacity to enforce the laws which, with all of the new decrees, has now become its "absolute incapacity." Rather than adopt, as the government seems to have, an all-or-nothing solution - where the Indian is either totally submitted to the will of its guardian, or is arbitrarily declared to be not an Indian at all - many Indian specialists in Brazil feel that work should be done to improve the legal relationship of the Indian to the state, and FUNAI's ability to enforce existing law.

In the meantime, what can be done to prevent the various legal projects currently in Congress from passing, and to confront the serious consequences of decrees already put into effect? In Brazil, part of the strategy now being planned by Indian leaders and support organizations rests on bringing these acts to public attention and to international forums such as the United Nations Human Rights Commission and the Sub-committee on Racism and Racial Discrimination in Geneva. Legal strategies are also being formulated. On the international level, indigenous defense organizations collaborate by publicizing the situation and assisting the movement in Brazil. Cultural Survival and the Anthropology Resource Center, for example, recently sent a letter of protest to the Brazilian government, with copies to individuals and organizations concerned with the Indian situation.

Brazilian lawyers, anthropologists, Indian leaders and support organizations recognize, however, that more fundamental changes are urgently needed in Brazilian Indian policy. These include the following:

* removing the FUNAI from the Ministry of the Interior and creating a special agency for Indian affairs in the Executive;

* restructuring FUNAI according to the plans proposed by Mario Juruna in April of this year;

* recognizing Indian rights to legal representation independent of FUNAI;

* recognizing Indian rights to full participation in decision-making with regard to projects that affect their lives; and

* recognizing the rights of indigenous cultures to remain distinct from the national society, and of indigenous communities to have the capacity for autonomous self-government.

As Roberto Cardoso de Oliveira, Brazilian anthropologist and recognized specialist on Indian affairs, has written, cultural pluralism, centered on the exercise of respect for difference and autonomy, must constitute the 'basis of a new Indian policy in Brazil.

Article copyright Cultural Survival, Inc.